Why Samuel Courtauld Championed Impressionism’s Radical Spirit

From works by Renoir to Cézanne, paintings from the Courtauld Collection go on show in Paris for the first time in 60 years

From works by Renoir to Cézanne, paintings from the Courtauld Collection go on show in Paris for the first time in 60 years

In 1922, the British textile magnate Samuel Courtauld and his wife Elizabeth bought a small, intimate painting of a woman bending down to tie her shoe. Rendered in feathery, indistinct brush strokes and pastel colours, it was one of the last works produced by Pierre-Auguste Renoir before his death in 1919. It is a painting that within the context of Renoir’s oeuvre – and in Impressionism in general – is easily overlooked, but its acquisition at a time of great suspicion towards modern French painting in Britain was daring and radical.

Woman Tying Her Shoe (ca. 1918) would come to be part of a small but remarkable collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art acquired by Samuel Courtauld between 1922 and 1931. Hung on the walls of the couple’s Mayfair townhouse, it includes some of the most iconic paintings of that period – Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), Renoir’s La Loge (The Theatre Box, 1874), Paul Gauguin’s Nevermore (1897) – and it formed the basis of the Courtauld Institute of Art, which was founded following Elizabeth’s death in 1931. When the institute – which offered the first opportunity to study art history and conservation at university level in Britain – moved to the neo-classical surrounds of London’s Somerset House in 1989, the collection was quietly put on public display. It has remained there, half-hidden from public consciousness, until last September, when the institute closed for an extensive two-year restoration project. Exhibited at London’s National Gallery this winter, the Impressionist and post-Impressionist collection is now on show, for the first time in 60 years, in Paris, at the Fondation Louis Vuitton.

‘It is important to place contemporary art within its historical context,’ says the foundation’s artistic director, Suzanne Pagé, following a tour through the building’s vast, asymmetrical Frank Gehry-designed spaces. An exhibition of contemporary art exploring painting will run concurrently to the Courtauld show. ‘But it is also important to show these hugely significant works in a new context, so that people can have a real, physical relationship with art that they might know from reproductions but haven’t seen before. It is important that they understand just how radical they were at the time.’

This sentiment rang particularly true in Britain in the early 20th century, where Impressionism was ridiculed in the press and viewed with scepticism by conservative museums. A ‘degraded craze’ practised by ‘modern French art-rebels’, as Lord Redesdale, a trustee of the National Gallery, wrote in 1913, Impressionism was considered too new and too French for its acquisition into national collections. It was Courtauld, along with other prominent supporters of Impressionism, such as the artist and art critic Roger Fry, who changed public opinion and critical reception of the movement in Britain. Courtauld’s collection, and his grant to buy works for public galleries – he is responsible for the National Gallery’s eventual acquisition of Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) and Georges Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884) – was central to establishing the reputation in Britain of some of the most influential figures in modern art.

Courtauld largely collected for himself, consigning works and living with them before he bought. He was much more a connoisseur than a critic who seriously championed the new, disruptive art. But this ‘authentic relationship’ with the work, as Pagé describes, led to Courtauld buying 15 oil paintings and watercolours by Paul Cézanne, an artist openly vilified in Britain as a charlatan. He is now considered by many to be the father of modern art, who point to his experiments with space and form in works including The Card Players (1892-96), Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine (1887) and Still Life with Plaster Cupid (ca. 1895) – all works collected through Courtauld’s passion for the artist, but which contributed significantly to the scholarly reception of the artist.

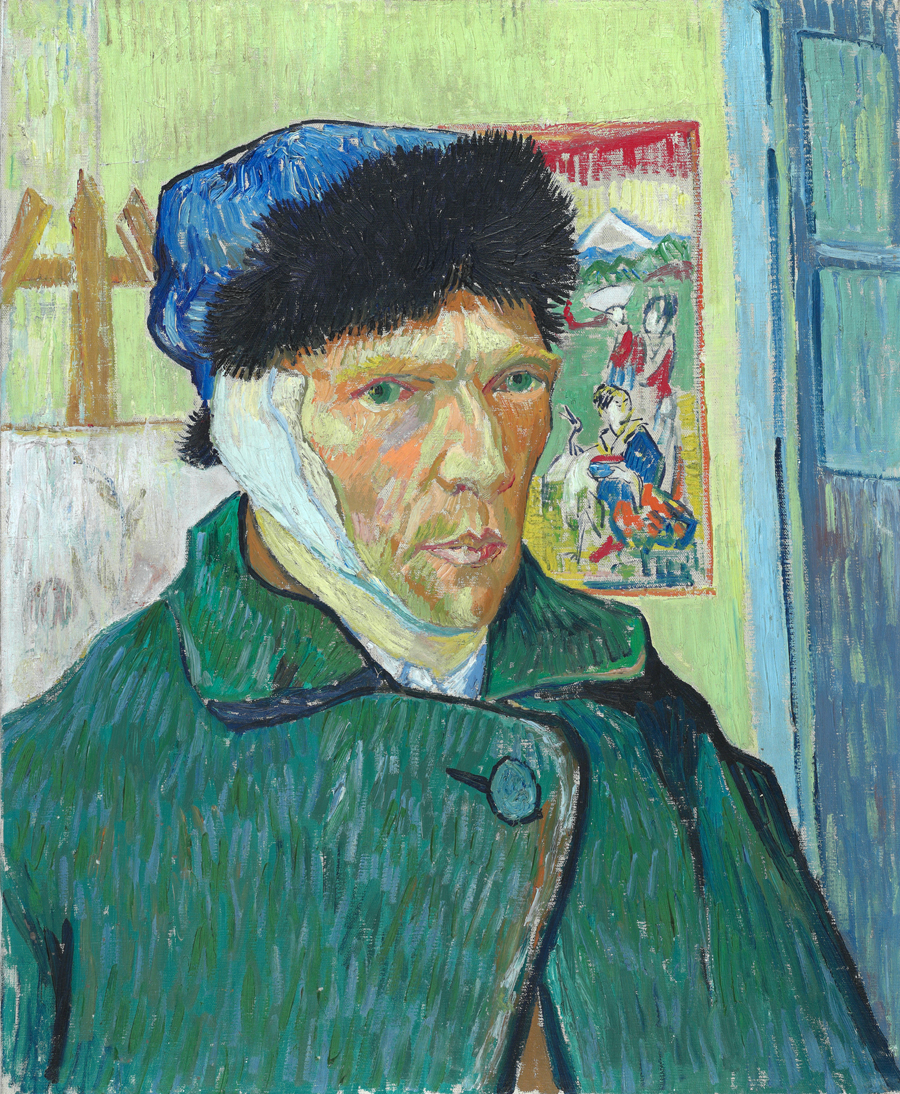

I studied at the Courtauld Institute and came to know the gallery well. Viewing the collection in Paris, hung on walls painted in soft pastel colours – blues or pinks or greens that gave the paintings a lively, contemporary resonance – I saw the works with an after-image, as they had hung in the 18th-century interiors of Somerset House. In Paris, one of the better-known paintings from the collection, Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889), has been placed in a recess in the wall, in a room, empty of anything but art, that would be sterile if it weren’t painted camellia yellow. It is a place to look and to analyze, to examine the thick impasto brush strokes and to discuss the inclusion of a print by Sato Torakiyo in the background. In London, the self-portrait hung above an antique table, under painted ceilings of bubbling cloud and cherubs, between two windows that looked out onto the wide, white stone courtyard of Somerset House: it was more relaxed and more – ironically for the gallery of an institution of art history, but in keeping with the way in which the collection was formed – enjoyable.

I am still fond of those densely ornamented, rarely occupied rooms in London but, away from the idiosyncratic setting of Somerset House, these 60 paintings in Paris are enlivened by their change in circumstances. Here they can be seen anew. More than a celebration of Courtauld – ‘the businessman who bought with his soul’, as Pagé puts it – and his progressive collecting, this exhibition shows how these great works will continue to offer up new meanings and ideas as their physical and critical contexts change.

‘The Courtauld Collection: A Vision for Impressionism’ is on view at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France, until 17 June

Main image: Édouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882, oil on canvas, 96 × 1.3m. Courtesy: Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris and The Courtauld Gallery (The Samuel Courtauld Trust), London