Against Taste

Artist Peter Wächtler talked to Walter Swennen about the pitfalls of poetry and painting as an impure practice

Artist Peter Wächtler talked to Walter Swennen about the pitfalls of poetry and painting as an impure practice

Chinese translation: ![]() againsttaste.pdf

againsttaste.pdf

Peter Wächtler What did you take away from the experience of installing your exhibition at Kunstverein Düsseldorf?

Walter Swennen The show includes paintings from the early 1980s until now, and it’s very nice for me to see the periods being mixed. I couldn’t say which work is from which year, really. It’s strange!

PW So, do distinctions between individual works become blurred; do they become part of one big work at some point?

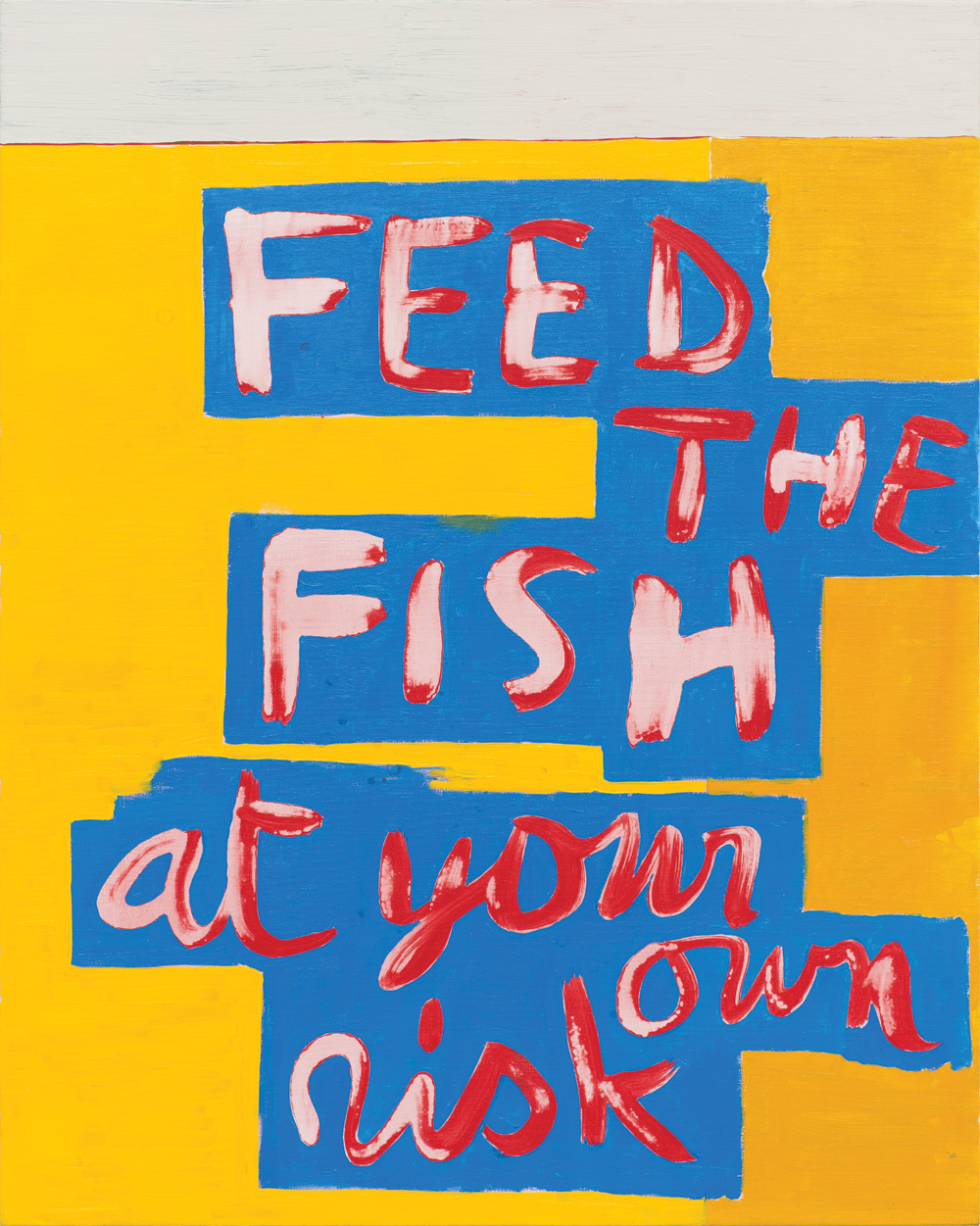

WS Well, no, there are distinctions in my work, a kind of conflict between image and painting going on. In the 1960s and ’70s, I had been more focused on words, but words in the graphic sense – typography. I was also interested in translation problems. In the early 1980s, I got a large studio and I took big sheets of paper and began to paint words onto them. It was funny to write words in such a physical way. Little by little, it became clear to me that images and words are essentially the same – they both belong to the realm of literature. The real opposition is not between image and word, but between image and word on the one hand and painting on the other.

PW In press releases – whether for your 2013 retrospective at WIELS in Brussels or the Kunstverein Düsseldorf show – it’s always mentioned that you used to write but then stopped. And that inevitably evokes the idea that you switched to a more direct, physical medium – while keeping an intellectual aura that someone who has always been a painter may never achieve.

WS For me, in the beginning there was indeed poetry. There was Stéphane Mallarmé and also there was, around 1965, the first translation into French of the Beat Generation poets – Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, etc. And that was a shock. They were such long poems. As Mallarmé claimed: poetry isn’t to do with what you have to say. I had nothing to say and, in the beginning, I was trying to be lyrical, but it was false. And then, little by little, I began to have an interest in concrete poetry: calligrammes. I also think that the work of Marcel Broodthaers, whom I knew, has to be situated more in poetry. He would have admitted that he had more interest in images than in painting; he did, in fact, once say: ‘I’m not interested in Cézanne and his apples.’

PW You claim you had nothing to say – did that change after you switched to painting in the early 1980s?

WS No, absolutely not. I was happy that I became a painter because I thought painters don’t have to speak. And anyway, from the 1960s on, I had been painting, and studying painting, privately.

PW You don’t write poetry anymore?

WS No, and I don’t read poetry anymore either. I never read much literature – only crime stories and Franz Kafka. And a little bit of Baruch Spinoza. I was very interested in philosophy when I was young. I had a girlfriend in Germany at the time and she later showed me a letter I wrote when I was 16. My plan for the future was to become a philosopher – an independent philosopher, not an academic one. And, to pay for my life, I would be a painter and sell paintings. It still seems to me to be a very good plan. But it took me a long time to realize it. I’m a very shy man – I’m not really in the art world, which is partly my fault – so I feel very isolated and I’ve never had much feedback on my work, although I think that’s also a good thing. What’s more, I don’t have a trademark style and that’s a problem for galleries and collectors.

PW Yes, but you had a show in New York in 1992, at Nicole Klagsbrun, and another in 2015 at Gladstone Gallery. There was also the retrospective at WIELS in 2013. So how did things change, in terms of your isolation?

WS It wasn’t until the exhibition at WIELS that I became aware I was apparently important for a younger generation of painters. They hadn’t come to tell me – I guess I don’t seem very approachable. So, for me, it was a revelation. I’ve known the gallerist Xavier Hufkens since the 1980s, and he always wanted to show my work in his gallery, but he’s a very respectful man and so he didn’t ask. He waited and then, after the WIELS show, I said: ‘Xavier, fine, I will work with you.’ So, now I finally have a gallery, but it doesn’t really have much to do with the WIELS show itself – it has to do with me. I was tired of working all on my own; what I needed was a good gallery.

Then, I had a visit from Barbara Gladstone – she’s sometimes in Brussels, as she also has a gallery here – and we drank a lot of coffee and she said: ‘Have you had an exhibition in New York?’ After all these years, it’s quite pleasant working with the big galleries – in New York, I understood what it is to live like a king. I would like to be a king one day a week!

'The real opposition is not between image and word, but between image and word on the one hand and painting on the other.'

Walter Swennen

PW Thinking of your Kunstverein Düsseldorf show, I like the idea of a no man’s land that is filled with the letters of the alphabet, and very plain images. Still, there is a feeling that the paintings were made by someone who is deeply invested in them. When I see, for example, your painting of a coffee pot with the year ‘1946’ written on it, it seems very direct, concrete – and, yet, open to a lot of associations.

WS Sometimes people ask me: ‘Do you go into shops and search for old comics or that kind of stuff?’ I don’t. I don’t go looking for things. I encounter them – a comic, one of my drawings – because I consider them on the same level as images from other sources. You know the French term Système D? It means to live by one’s wits, to improvise with what’s at hand. In France during the 1950s, after the war, there was a lack of tools and materials for making art, so artists just began to use whatever they found.

PW Your work is also a bit Système D?

WS Yes, because it’s about the process. I do something and I say: ‘Ok, enough for today, it’s late now.’ But then, the next day, I carry it forward. It occurs on the canvas itself. It’s improvisation – slow improvisation.

PW It’s improvised, but with aesthetic elements that, in themselves, are pretty clear – there is no doubt, say, that the knight depicted is a knight. So, these elements don’t necessarily ask for Système D – but you subject them to it anyway, and that’s a very charming approach. Is this to prevent the motifs from becoming symbolic, commenting on this or that in culture?

WS In King Leo (2002), the lion with a crown is painted by the book, but is still subjected to the messiness of the overall painting. In French there is an expression, contre son goût, and I do try to paint against my taste – not only against ‘good taste’ but also in the spirit of disinclination, which I consider a virtue. It’s difficult to paint against taste. But painting has been very difficult for a long time. At the National Gallery in London recently, I saw paintings by John Constable in the flesh for the first time. I had always thought he was a specialist of spinach – only hues of green, green, green. But if you see his work in reality, it’s fantastic. Same with Titian’s Diana and Actaeon (1556–59). The image is what it is but, if you stand on the left-hand side of the painting, about a metre away, you predominantly see Diana’s red dress hung on a line. It’s a painting exploring all the possibilities of the colour red. In the end, I thought: all those painters, they lead double lives, with the image as their official partner and painting as their lover. That’s what we call a painter’s painter. As a painter, you notice the red in Titian or the hues of ultramarine in Constable, and you can stay to look at them for a long time.

PW I also sometimes like to see a work reproduced – say, an old postcard pinned up somewhere. But then, when I go to a museum and see the actual work, it’s often too much: I cannot face the original. I try to respond to it more than I really do, or even want to.

WS I know what you mean but, still, I like to see, say, The Battle of San Romano (1438–40) by Paolo Uccello in the flesh. It’s a very large painting, like in CinemaScope, with soldiers on horses carrying long spears – so it becomes very abstract also.

PW It seems a decisive thing to look at these masterpieces one painting at a time. What I liked about your show at WIELS was that it included over 100 paintings, yet I didn’t feel bombarded. It seems you allow people to observe your paintings in a way that is not too demanding but, equally, is not ignorant or insensitive.

WS At wiels it was mixed but there was a certain chronology and there were sections – the big works on paper from the early 1980s, for example. What I prefer about the exhibition at Kunstverein Düsseldorf is that these works on paper are hung between the paintings. That way you see better what I do, I think.

PW The notes and sketches that were on display in vitrines also served to demonstrate that the paintings are not done ‘just like that’. Showing them was almost like saying: ‘He also thinks about what he does,’ which I personally found a bit problematic.

WS In fact, the drawings actually began without any connection to the paintings. I began working on them when my children started going to school in the late 1970s. Before then, I had been more of a night owl, not really getting to the studio until late in the afternoon. But, suddenly, I was there at nine o’clock in the morning. I’m an artist, but I was a Catholic before that and doing nothing is a sin. So, I thought: well, I will do nothing with a pen in my hand. I began to scribble, like you do when you’re on the telephone. I didn’t look at the sheet. When the page was full, I put it in a box under the table. It’s a Zen exercise: you do it, but you’re not concentrating on what you do. After a week, or a month, you open the box and there are 30 or 50 drawings that you haven’t looked at before. Some are very bad; others are interesting. I called it my compost. Sometimes, there were details where I thought: ‘Yes, that could become a nice thing in a painting.’ I did this for about ten years, each morning; it was an exercise, and a way to kill time [laughs].

'The idea of painting still seems bizarre to me; it's something very impure. There's always this conflict with representation.'

Walter Swennen

PW How does that kind of routine relate to painting?

WS There is a piece by Mario Merz from 1980, with the following words illuminated from behind: la pittura è lunga e veloce – ‘painting is slow, and fast’. The problem is how to deal with that contradiction. If you know exactly what you want to paint, you have a project and you have to only execute it – it’s boring, but you are occupied all day. I think that became important for René Magritte later in his life. He made extraordinary and bizarre, partly abstract, paintings until around 1928 or ’29 – and he painted them in a rather quick way. But then he came under the influence of bad friends, poets [laughs]. He essentially began to make images, not paintings. What I mean by that is it turned into an exercise of coloriage – colouring a preconceived design. The title became so important, and you have the feeling that it’s a joke in two parts: one part is written; the other is an image. I think the reason for this was that Magritte was a very melancholic man, and he needed to find an academic way of painting to keep himself occupied all day, to prevent himself from thinking negative thoughts. You’re busy, and so there are no little bicycles running around in your head.

PW Can you try to explain further the difference between making images and painting?

WS The idea of painting still seems bizarre to me; it’s something very impure. There’s always this conflict with representation. And it’s because of that conflict that I waste so much time in lectures on the subject. I also read many books about aesthetics, and the philosophy of art. But what’s frustrating is that, in aesthetics as a philosophical discipline, painting is usually reduced to an object of perception. That may be a good start for aesthetics, but it’s a bad start for art – the object of perception is, in fact, a physical thing, and somebody else did make it.

PW How does photography and reproduction come into that?

WS You can, say, put nine paintings on a page at about the same size that don’t have the same dimensions. So, it’s kind of a lie, because you aren’t looking at the painting; you’re looking at the flat image.

PW Which is good for some paintings – they really improve.

WS Yes, but it’s not an improvement if the painting process is directed towards looking good in reproduction. If, for example, it leads to the use of an inferior palette – say, just using magenta because magenta is good for reproduction. Painters are clever like that!

PW So, do you want people to look at your paintings up close?

WS Yes, of course, because that’s how I discovered what painting really is. I was six or seven years old and my mother took me to see flower paintings and it was boring – I hate flowers! So, I moved up close to the paintings, and then I realized I couldn’t see the flowers anymore, or any image at all, but thick strokes of paint. I was fascinated by that. My mother thought I had something wrong with my eyes, and we went to the doctor and, as it turned out, I was indeed short-sighted.

PW How did you get started on making your own paintings?

WS In the early 1960s, when I was still a teenager, I was quite influenced by Jean-Paul Riopelle, whose work I had seen in an exhibition in Paris. He painted with a palette knife, as did the artist who first taught me how to paint. At that time, using a knife was generally considered kitsch, but what’s good about it is that you can use it in a very unorthodox manner. I like to use instruments over which you don’t have total control – a paste brush, say, or a broom.

PW Is it about having to improvise a little with things you can’t fully handle?

WS Yes, but on the basis of certain underlying ideas. If, for example, you can clearly see that your painting consists of two things – a background and an object – then it’s dead. There has to be a third element: you have to find something different than those two things. Two is too easy.

PW So, there are always at least three elements in your works?

WS Yes, it’s a practical rule I invented for myself. Sometimes, I notice that the third element is still missing, but I don’t know what is, and it can take a lot of time until it occurs, often by chance. When I’m alone in the studio, I frequently say to myself: ‘One, two, three.’