An (Almost) Interview with Iain Sinclair

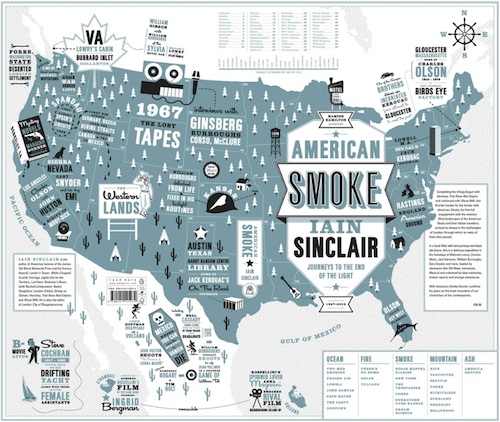

For his new book American Smoke, Iain Sinclair travels in search of the writers who inspired him as a young man

For his new book American Smoke, Iain Sinclair travels in search of the writers who inspired him as a young man

“It’s not that these are uninteresting questions,” Iain Sinclair assures me when he emails one gloomy Sunday afternoon to explain that he can’t participate fully in an interview. “They’re good questions. But it’s been a period of constant movement for me and too many events. I feel that the moment has already slipped away. And I do begin to grind my remaining teeth at the thought of the interview questionnaire, like getting permission to cross some cultural border to a place you are no longer sure you want to go.”

The phrase “cultural border” is pure Sinclair – poetic, overblown, combining the physical and the imaginary – and might have formed the basis of the kind of answer he feels unable to provide. So why not just get on with the interview? “It involves my performing an autopsy on a still–quivering book,” his email continues. “And I find that it’s something I can’t do.”

Despite the promotional demands that come with the mainstream publishing territory Sinclair now occupies, he remains productive. American Smoke (Hamish Hamilton, £20.00) is the final installment in a psycho–geographical trilogy that began with Hackney, That Rose Red Empire (2009) and continued with Ghost Milk (2011), his act of literary resistance on behalf of the East London world he saw being erased in the build-up to last year’s Olympic Games. At 70, he’s still absorbing new influences, as demonstrated by the role the late Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño plays in American Smoke. “The achievement of Bolaño,” Sinclair writes, “is to find his necessary place.”

For nearly half–a–century, Hackney has been Sinclair’s “necessary place” – the home where he’s produced his best writing and the subject of it – but, in his new work, he travels “to the end of the light”, the book’s subtitle, which stands for the landscapes of the American writers he loves. He’s said that he wanted to go “back into a sense of freedom and anarchy and energy that I got in dealing with people like Charles Olson and Allen Ginsberg and Malcolm Lowry in the past, in person or in books.”

This restlessness, I suspect, is connected to what he calls “the enforced intimacy” of the Olympics and the way the Games altered East London. Long before all that, however, dealing with Ginsberg involved a stilted 1967 interview which Sinclair describes in American Smoke. Like the Q&A below, it’s an anti–interview, or perhaps you’d call it a “bad interview.” After all, American Smoke concerns “the eternal recurrence of bad journeys”.

Max Liu: What is a “bad journey”?

Ian Sinclair: The book itself is a bad journey. And the old Beckettian requirement to write it, despite everything. Along with a compulsive fascination with Albert Speer’s imaginary tramp across the world (while fixed in the prison yard) and John Ledyard’s epic, so cruelly turned back on itself, and Malcolm Lowry’s hallucinatory tourism in the pissy footsteps of his own fictional bad trip.

ML: As well as your 2011 trips to the Massachusetts homes of Olson and Kerouac, and your West Coast road trip, American Smoke draws on interviews with Gregory Corso and William Burroughs from 1995. Did you always know they would be worked in to a book?

IS: The book becomes the book. I made notes when travelling, but I didn’t write anything of substance. I didn’t have the original interviews with Burroughs and Corso pegged, at that time, for a future slot. But obviously I was well aware that the day might eventually arrive.

ML: Roberto Bolaño is a thrilling presence throughout American Smoke. What impact have his books had on you?

IS: Bolaño was the ghost, the Virgil spirit in this Dante pilgrimage: the way he exploits so beautifully the myths (grunge and heroic) of the figure of the poet. I’m also interested in the intersections of biography, crime research, politics, poetry, fiction. The way he says that all English writers want to become detectives.

ML: You write: “All his life Lowry relied on the longshot, the amazing coincidence…” There are several coincidences in American Smoke, and many throughout the trilogy, but is your work dependent on them?

IS: I expect coincidences. And they usually oblige. The trick is to untangle them and not to go completely under.

ML: I’m interested in your wife Anna’s role in this trilogy. She accompanies you on the journey from Canada to California. Do you run chapters past her and do the two of you have conflicting versions of the events you describe?

IS: This ‘Anna’ is a fictional construct and not the ‘real’ woman. It’s not that these episodes didn’t happen, but that my telling is strategic, to work in terms of the narrative. Without, I hope, offending my companion. Anna never reads anything until it reaches paperback and the heat is off. “You can’t say that.” All too often I do. And I’d stress again that this book (like Hackney) is a kind of novel. Some of the characters are disguised, some are invented. It’s a manipulation.

ML: In San Francisco, you meet an old Beat poet named Carl Shutter who says that you will never understand American writers. Do you agree?

IS: Carl Shutter telling me that I’ll never understand American writers is accurate for Carl. There is no such person, I’m afraid.