Archie Moore’s Conflicting Energies

From installation to innuendo, at Brisbane’s Griffith University Art Museum the Australian artist mines the inbetweenness of identity and language

From installation to innuendo, at Brisbane’s Griffith University Art Museum the Australian artist mines the inbetweenness of identity and language

The Australian artist Archie Moore is the lead singer in a metal band called Eggvein – or ∑gg√e|n. His stage name is Magnus O’Pus and, like all good front-men, he performs without a shirt, wearing tight black jeans and a goth-version of a Marie Antoinette bouffant wig that, á la Cousin Itt, covers his entire face. Difficult to categorize, the band is partly a joke and partly a therapeutic outlet for the working-class masculine angst of its members, who include artist David M. Thomas – a key figure from the artist-run-gallery scenes of Sydney and Brisbane – on an extremely loud guitar. When performing, Moore, who turns 48 this year, appears charismatic, shy, depressed, angry and, given the band’s raucous sound, oddly obsessed with his lyrics. These conflicting energies spill over into his art practice, which centres on memory and the symbolic slippages he sees as integral to his Aboriginal identity, always shapeshifting across media in unexpected ways, from taxidermied dogs (Black Dog, 2013) to the manufacturing of his own cologne (Les Eaux d’Amoore, 2014).

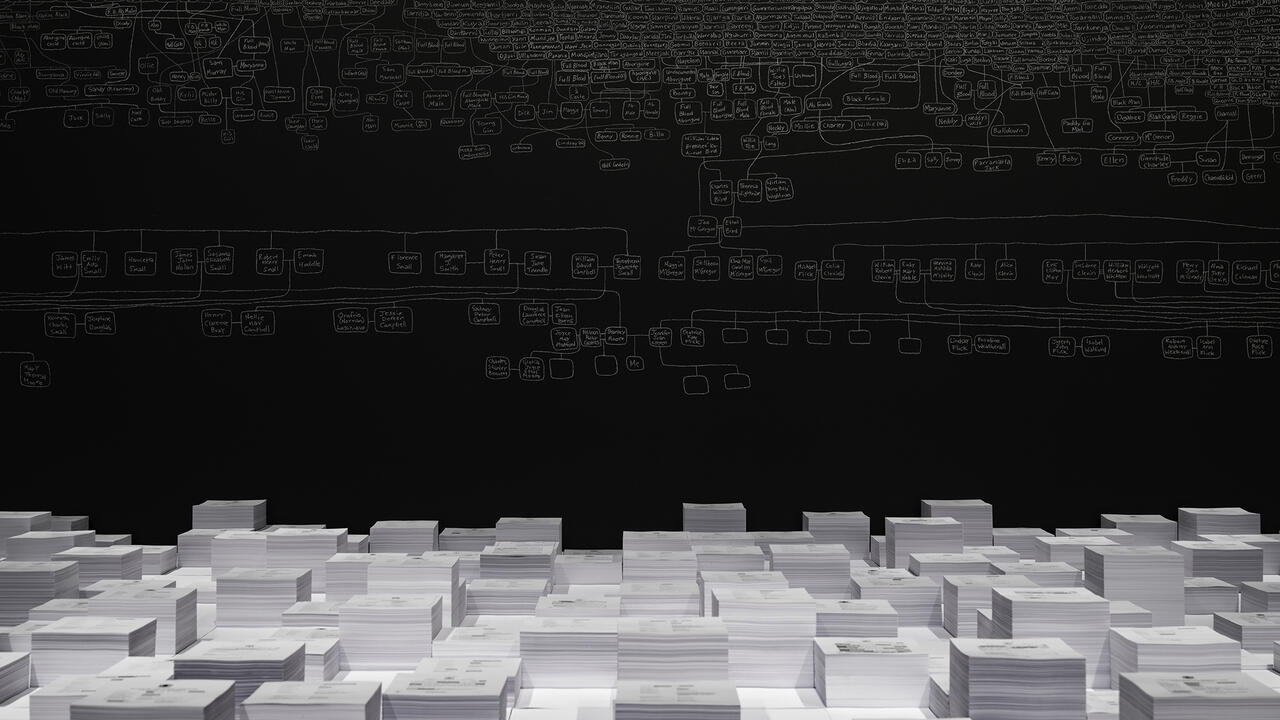

As the current exhibition at Brisbane’s Griffith University Art Museum, ‘Archie Moore: 1970-2018’, makes clear, Moore’s output is mostly unpredictable, yet housing and spatial construction have been recurrent features, showcasing the artist’s exceptional skills at installation design. Gaining national recognition in the late 2000s, his series of sculpted books, ‘Maltheism’ (2007) – the belief that God is evil – consist of open bibles whose pages have been delicately cut and folded to form small churches, adjacent to biblical passages referencing dispossession and destruction. The works were influenced by the dominating presence of Christianity in the artist’s life growing up in the small Queensland town of Tara (located about 300 kilometres west of Brisbane, with a population of around 800). Moore, whose mother is Aboriginal and whose presumed father is white (and religious), felt the childhood effects of what can only be described as ‘Queensland redneck syndrome’. As part of one of only two Indigenous families in the town, he denied his heritage because of the constant threat of racism. However, since his early twenties he has spent his life coming to terms with the gaps in his own history and those of Australia’s. Beneath the graceful aesthetics of his paper churches is a lot of anguish and colonial pain, but you wouldn’t know it by looking at them – their vulnerability is their power.

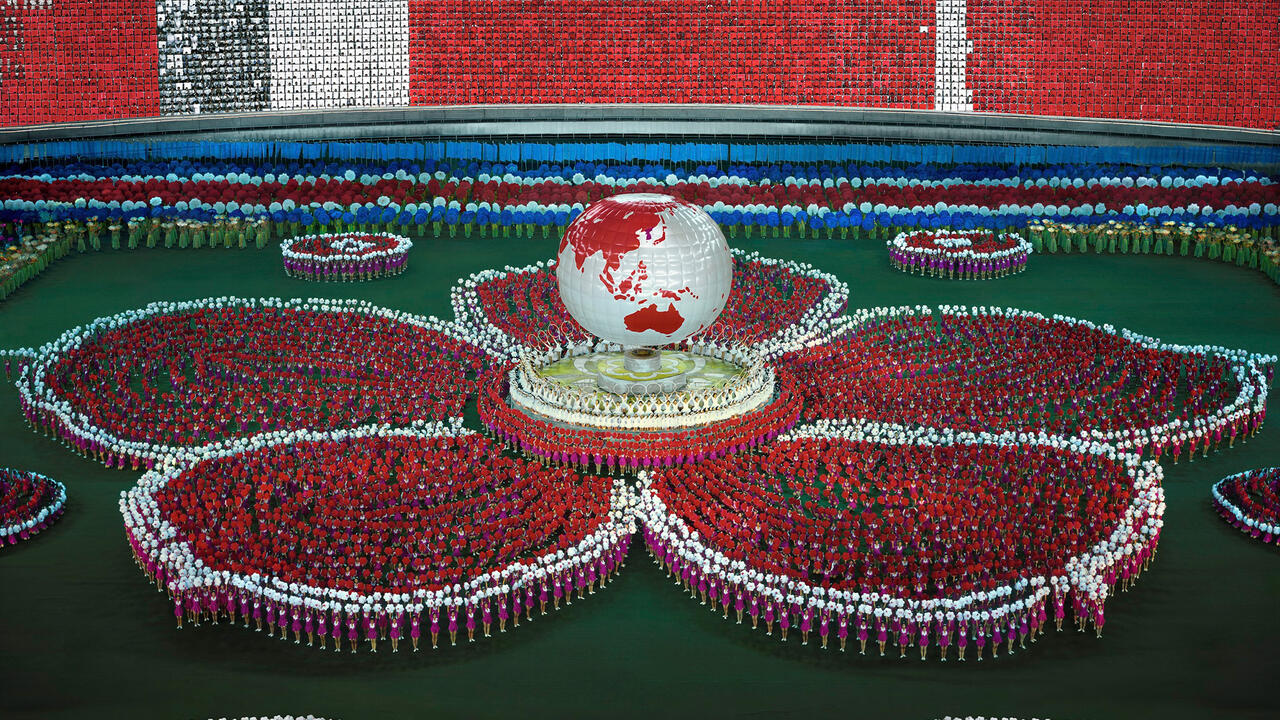

For the 2016 Biennale of Sydney – curated by former Hayward Gallery director Stephanie Rosenthal – Moore constructed a 1:1 replica of a brick hut overlooking the site of Sydney Opera House that was originally built for Bennelong, the late-18th- and early 19th-century Aboriginal (Eora) elder who, post-invasion, was an important interlocutor between local Indigenous and settler cultures. A Home Away from Home (Bennelong/Vera’s Hut) (2016) was made to resemble the exterior of Bennelong’s actual hut, but the interior was modelled on the house of Moore’s late grandmother, relying on conversations with relatives to reconstruct its corrugated iron walls and dirt floor. Here, Australia’s first colonial home for an Aboriginal person also housed the memories of a close but distantly recollected relative, whose life-trajectory was fundamentally shaped by British arrival all those years ago, and not for the better.

Moore is fascinated with double entendres, puns and linguistic dualities, so it is particularly fitting he shares his name with a well-known African-American boxer of the 1950s and ’60s. In the early 2000s, after a stint studying art in Prague, Czech Republic, he produced his first text-based paintings using blackboard paint and white pastel, displaying words such as ‘cunt’, ‘poof’, ‘arse injected death sentence’ and ‘Boong’ (a derogatory word for an Aboriginal person) as exemplars of a malevolent pedagogy. This led to a video work, False Friends, (2005–ongoing), which focuses on just that – a ‘false friend’ is the term for a foreign word that looks or sounds similar to a word in another language, for example, the English word ‘gift’ means ‘poison’ in German. Here, Moore mines foreign language tapes to listen out for English-sounding dialogue, which he appropriates and accompanies with text that spells out the foreign quotations as if spoken in English. The short bursts of words and phrases are characterized by Carry On-style innuendo and E.E. Cummings-style syntax, such as the French-sounding: ‘a trailer, surreal murder mystery, a nurse alone, her boob, a chauffeur, become harder, gooey runny…shower, a chauffeur, jealous.’ In Moore’s hands, literalness can be abstruse.

As a front-man, Moore doesn’t really fit in, even in a music genre synonymous with outcasts. Obsessed with inbetweenness, or, rather, with finding a place in the out-of-place, he offers us homes away from home, and meanings where there might be none. The sculpture Bogeyman (2017) – which comprises a human stick-figure made of wood with a white sheet draped over it like a scarecrow ghost – evokes colonial stories about spectral natives as well as their reverse: stories of Aboriginal people believing their white colonizers to be ghosts. Yet, following Derrida’s concept of ‘hauntology’, the work might also be the perfect metaphor for Moore’s practice overall, whose symbolic slippages haunt cultural and political hegemony as ghostly ethical injunctions. An artistic heir of the American artist Jimmie Durham, Moore portrays identity as deeply felt, but also as symbolically constructed and potentially constricting. With the label of ‘urban Indigenous artist’ comes an expectation to voice a sociology, spirituality and politics of art. Instead, Moore finds nothing solid behind such distinctions, and instead takes issue with them all.

‘Archie Moore: 1970-2018’ is at Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane, Australia until 21 April.

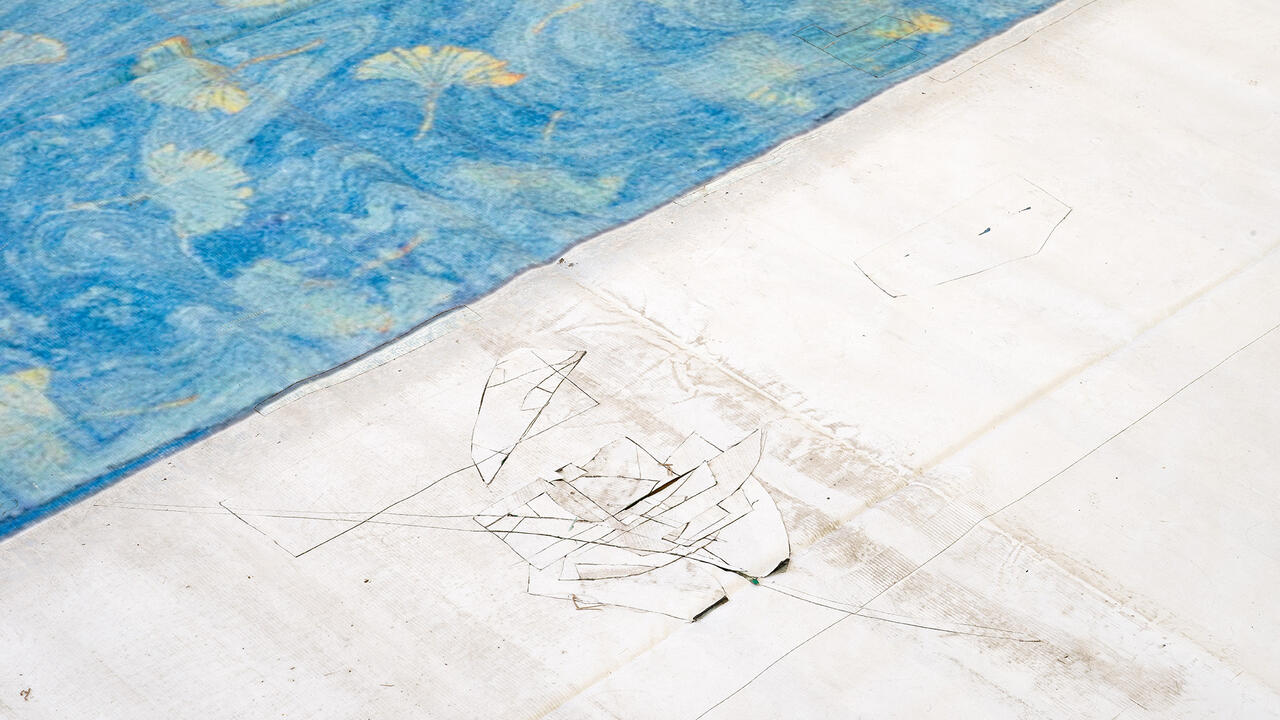

Main image: Archie Moore, Nothing Is Going My Way (detail), c.1996, synthetic polymer paint on found painting, 49 x 64 cm, Courtesy: Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane