The Architect Who Wanted to Make Dying Illegal

A remarkable new collection of writings by Madeline Gins makes a strong case for her work as an uncategorizable poet

A remarkable new collection of writings by Madeline Gins makes a strong case for her work as an uncategorizable poet

The late American writer and architect Madeline Gins was probably best known for the Reversible Destiny project (1987–2010): a theoretical collaboration with her husband, Shusaku Arakawa. They wrote treatises against death (in books such as Architectural Body, 2002, and Making Dying Illegal, 2006) and designed spaces intended to facilitate their inhabitants’ immortality. In Reversible Destiny, speculative philosophy and abstract science-fiction aligned with an imaginative use of physical space: their constructions – five of which have been realized – are characterized by uneven floors and walls, clashing bright colours and obstacle course-like hindrances to inattentive walking that keep occupants on their toes. A retrospective of their work, ‘Reversible Destiny/We Have Decided Not to Die’, was held at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1997.

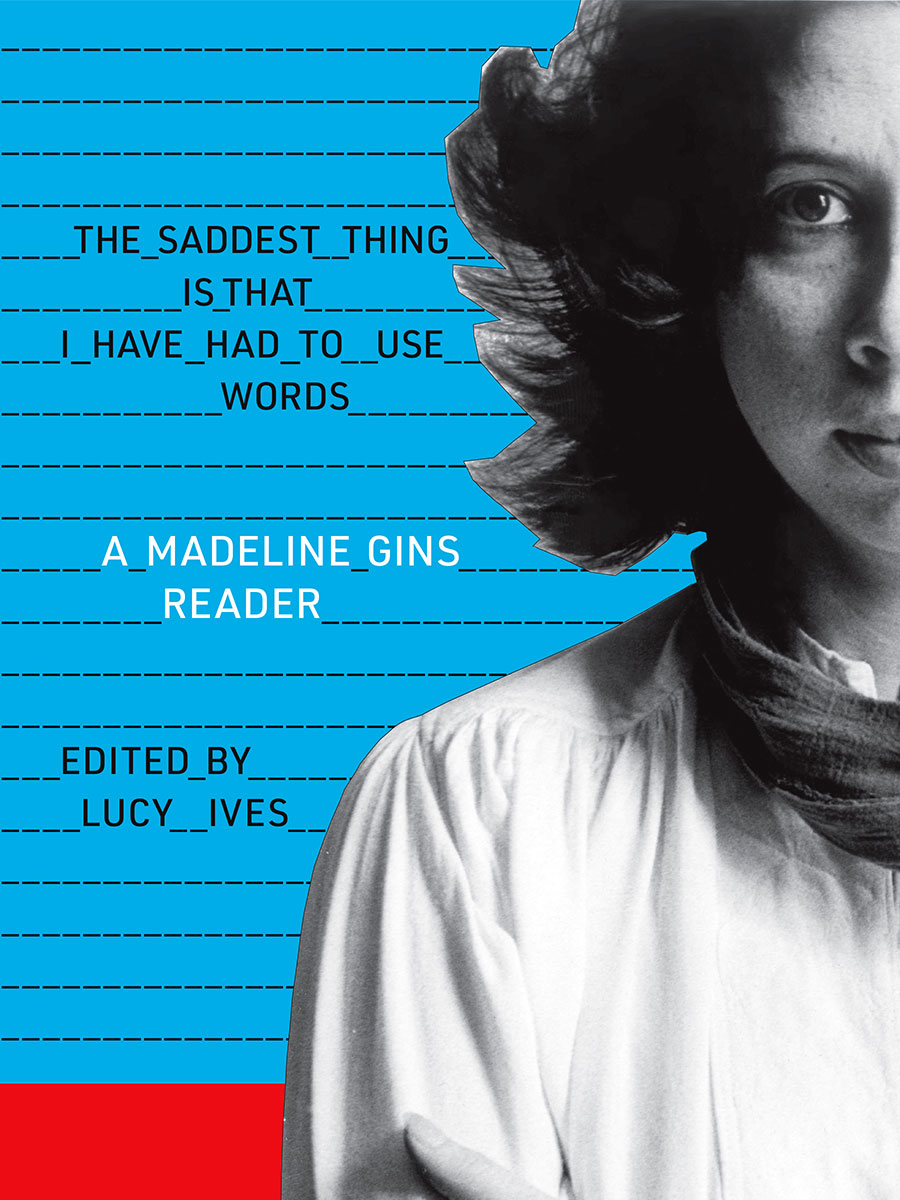

The Saddest Thing Is that I Have Had to Use Words: A Madeline Gins Reader (2020), edited by the novelist and critic Lucy Ives, is a gift: it brings back into print a great deal of work that has long been unavailable – including fiction, poetry, essays – as well as previously unpublished texts. It also makes a strong case for Gins’s importance as a writer and poet. Outside of an art context, readers of poetry have long known of Gins as an author of singular experimental texts that don’t fit neatly into categories: her writing has the intellectual playfulness of conceptual art, the conversational spontaneity of 1960s second-generation New York School poetry and the formal intractability of Language writing, but it exists on the edges all of these tendencies – and never quite found a comfortable home in any creative scene while Gins was alive. Later in life, Gins almost stopped publishing, but still travelled in literary circles. A frequent presence at readings in New York, she was especially supportive of younger writers (who, in turn, sought out and read her work).

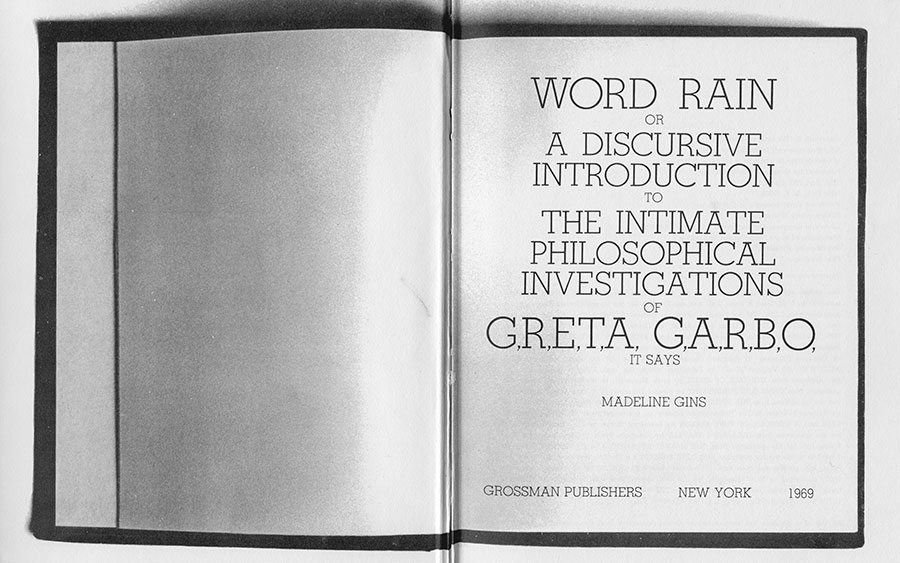

Her novel WORD RAIN (1969) and book of poetry What the President Will Say and Do!! (1984) are substantial engagements with philosophies of language, especially concerning the malleable nature of reference and rhetoric. While never succumbing to self-seriousness, they don’t shy from ponderous thought or meta-commentary. WORD RAIN – re-published here in a full facsimile of the original edition – mixes disparate narrative threads with a simultaneously earnest and tongue-in-cheek pastiche of structuralist analysis:

As I started to read the third paragraph of page thirteen, I finished up the crabmeat sandwich, which was good. Now I found myself reading word for word. The second line was about the nature of the logical guess. The third line was an extension of the premise of the first two. The fourth sentence had the words: seems, getting, to, be, quite, late. Although this sentence was necessary for the progress of the story, it tended to warp that particular paragraph out of shape.

Further down the page where this passage appears, an image of a thumb holding the book open obscures part of the text. This sort of conceptual self-reflexivity doesn’t quite function as a straight-forward commentary on the work; instead, it points to the physical act of reading without musing on it. In some ways, this move exemplifies what’s uniquely intriguing about WORD RAIN: it takes philosophy seriously without indulging in profundities. Gins is more interested in the experiences of thinking, reading and speaking than she is in generalizations.

Her attention to both the sensuality and silliness afforded by wordplay is apparent in the exuberance of her writing but, just as importantly, a strain of melancholy runs throughout. Much of What the President Will Say and Do!! involves exaggerating and transforming the tone of official political speech: it opens with many pages of absurdist all-caps imperatives (‘TUNNELS MUST CONTAIN TUNNELS!’), followed by short vignettes about a character named The Leader. But, later, the tone shifts, evoking a sense of loss.

A section titled ‘Brief Autobiography of a Non-Existent’ consists of a fictional autobiographical timeline written entirely in the negative:

1915: A bee did not sting me and cause a high fever which produced strange deliriums from which I still suffer.

1918: I did not begin to masturbate. I had no intention of playing hooky.

1919: My father did not inherit a fortune. My maternal grandmother never died. My unmarried aunt did not come to live with us.

Here, memory is paradoxical: it brings the past into the present, but only as something irrecoverable. This is also the animating tension of Arakawa and Gins’ Reversible Destiny project. According to their theories, one could reverse the aging process and court immortality through architecture: the experience of space can extract moments from linear time. Though their ideas border on the parodic, Arakawa and Gins always maintained a straight face: they used hyperbole to seriously question cultural assumptions about time and mortality.

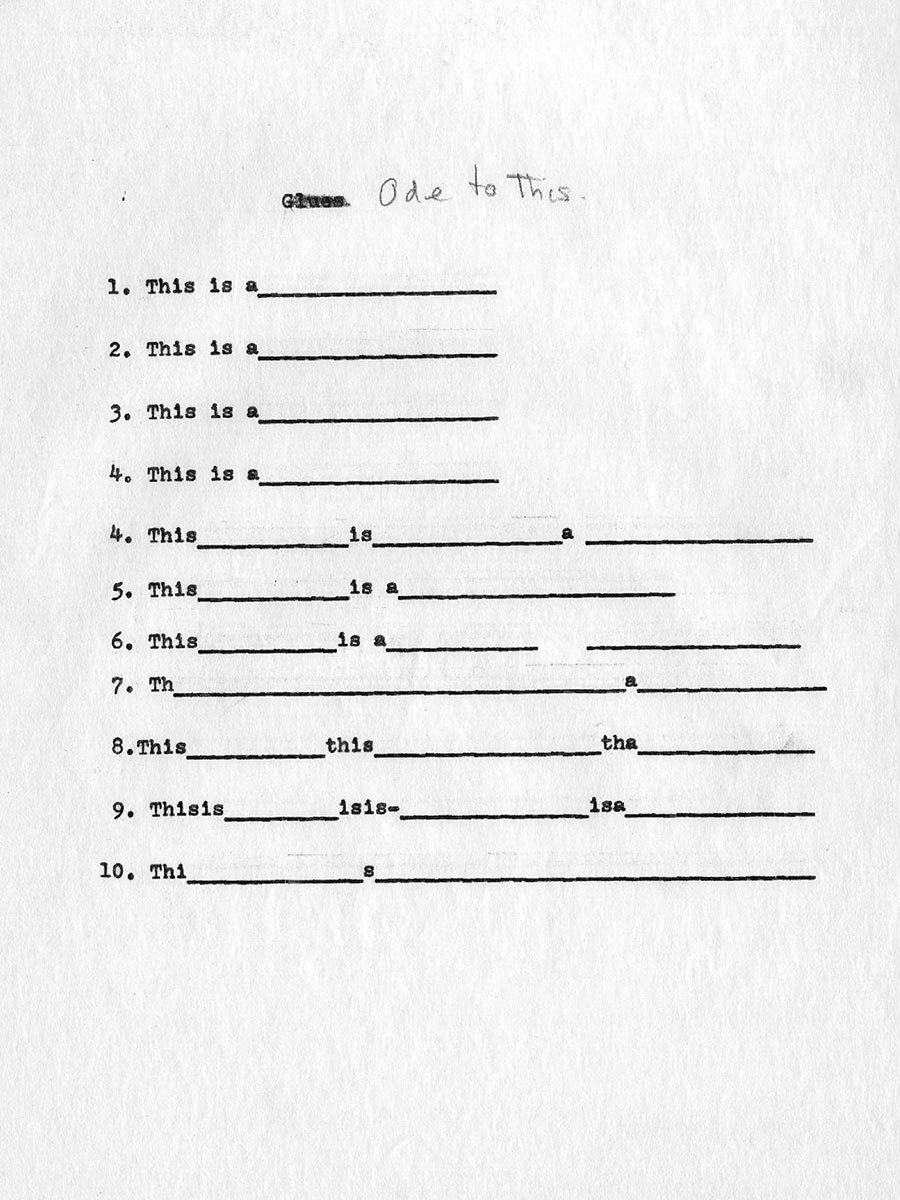

One of the real surprises and delights of The Saddest Thing Is that I Have Had to Use Words is the inclusion of early poems from the 1960s and ’70s, which have not been previously published. Many of these works take the form of numbered lists, as if each poetic statement had a place in a logical order. In a poem called ‘To Arakawa’, for example, the sketchy elements of a scene are enumerated: ‘4. Oh, look you have a pencil in your hand / 5. Shadow bitten / 6. You are full’. Counting, which almost inevitably suggests forward motion, is derailed by the inconclusiveness and partiality of the lines. But the numbers are not merely a parody of mathematical thinking: they are a way to separate phrases, setting them off from the rest of the poem so that they might linger a little longer, briefly suspended in time, not moving toward an ending.

This work didn’t quite fit into the literary landscape when it was written, and it doesn’t quite fit now. That’s because Gins was never concerned with being hyper-contemporary, nor with commenting directly on the day’s news. She was dedicated to a lifelong exploration of duration and ephemerality. While her architecture remains better known, that’s only one part of the story – this generous selection of texts is an opportunity to engage with the full scope of her thinking.