The Architecture of Fascism in Ingeborg Bachmann’s ‘Malina’

The newly reissued novel maps the intimate spatial connections between fascism and patriarchy in postwar Austria

The newly reissued novel maps the intimate spatial connections between fascism and patriarchy in postwar Austria

Ingeborg Bachmann’s novel Malina (1971; reissued by New Directions this year) follows the confessions of ‘an unknown woman’ as she shows the ways that the threshold of her private sphere is being manipulated, eroded and trespassed upon by three different men. The private sphere is a precinct of social life over which an individual usually enjoys a degree of authority, unhampered by interventions from governmental or other public institutions. The narrator delineates, however, that the distinction between spheres is problematic and that the private-sphere aggressions shown by the male individuals around her have merged with the public-sphere traumas of fascism. As a result, sharing an intimate space entirely removed from these vast events becomes untenable, destroying any chance of reciprocal relationships, contributing to what she terms the ‘virus’ of love, and eroding her sense of self. Throughout the novel, to counteract the negative forces encircling her, the woman attempts to maintain a fairy-tale world: one in which there is a suggestion of a third, utopian state between the spheres of female and male, public and private, where she can regain sovereignty over her own body and mind. But, at a certain point, this fictional retreat converges with her reality, and escape is seemingly attainable only at the cost of her evanescence.

The unknown woman’s relationship to the men – just as it is to fascism – is spatially intimate and distant simultaneously, which Bachmann uses technical language to reveal. Midway through the novel, the protagonist claims to be enamoured with the concept of ‘apparent wind’, which is wind speed measured relative to a person standing on a moving boat. Weather fronts are, of course, far bigger than people and come from a distant place, yet this particular term renders them personal. The novel is also studded through with the word ‘sidereal’, which pertains both to distant stars and to the specific location of an individual in relation to them.

These objective and scientific terms are then set against subjective personal relations. When first meeting Malina, the person with whom the unknown woman appears to live, there is no threshold and she writes: ‘I rammed into him as if someone had pushed me.’ A similar situation occurs when she meets her lover, Ivan: ‘my life, which once ran into someone else’s’. After these initial connections, both men quickly define the boundaries of their relationships to the woman. Malina soon loses himself in a ‘crowd’, demarcating his physical vacancy for the rest of the novel, raising the question as to whether he continues to exist outside of the narrator’s mind. With Ivan, on the other hand, she captures how he will later decide on the rights of her access to his domain: ‘I had no doubt I would accompany him, go home with him right then and there […] The borders were soon defined.’ Both male characters control the width of the threshold between the narrator and themselves, dominating through different types of detachment that then leads to direct, intimate encroachment because of the pain she personally suffers from wanting to be close to them.

By translating psychological concerns into physical spaces, Bachmann enables the reader to see just how controlling the male characters are, employing parameters that are already understood: distances, walls, partitions. In the book, as in reality, these boundaries between spaces are controlled by a host of patriarchal figures, whether real or internalized, and the traumas grow out of and reinforce this domination.

Contained within the title of the first chapter, ‘Happy with Ivan’, is the unknown woman’s ambition – although for Ivan the relationship is little more than a convenience for when he is not occupied at work, such as when he allows her to care for his children. He can utilize the attributes of her private sphere, has near-unlimited access to it, but she’s not allowed to move into his. The prose throughout the novel is agitated, fitful and full of grammatical oddments, as well as intercut with alternate and unexpected modes of conveyance: film scripts, musical scores, interview answers to unknown questions. Her conversations with Ivan, for example, conducted on the telephone after many hours spent chain smoking and waiting for him to make the decision to call, to cross a technological boundary, are riddled with glitches and voids and notated like poetry: ‘How I am? And you? / I don’t know. This evening? / I can barely understand you / Barely? What? So you can / I can’t hear you very well, can you?’ These sections convey the telephone’s capacity to create verbal contact – even though it’s not communicating anything fully – in the absence of a physical connection or shared space. The calls are symptomatic of their relationship, one in which Ivan keeps the narrator at arm’s length, controlling when she can enter his private sphere.

While the narrator perennially awaits Ivan, even though he rarely arrives or calls, Malina is all-too-present, almost in superposition, like an atom that can inhabit multiple places at once, a pervasive gaze that is perpetually watching. In one moment, whilst he is looking at a chessboard on which the protagonist had recently been playing Ivan, he comments on the poor quality of play from her opponent without referencing him directly. He also knows which glass to drink from: ‘How can he know it’s my glass and not the glass that Ivan left, also half full, but he never drinks from Ivan’s glass.’ Malina is omnipresent and, despite the passivity of his gaze, it still colonizes the woman’s private domain.

Ivan is physically present, when it suits him. Malina is a more elusive character and the reader is left only with traces of him. As the narrator says: ‘He always keeps his distance, because he is distance personified.’ She also has a tendency to refer to him using the female form of his name, Lina, along with feminine pronouns and, when discussing her childhood, she conflates him with her best friend, Melanie. Malina uncannily infiltrates the narrator’s world in many ways, suggesting that he could be part of her imagination, her innate patriarchal surveillance system.

The unknown woman’s father is also physically and psychologically trespassing on her private sphere. In chapter two, ‘The Third Man’, she seems to pass in and out of consciousness while reimagining the sexual abuse she may have experienced at his hands, so traumatic that it becomes an elusive subject described only obliquely through the nightmarish architecture that surrounds her. Bachmann often employs architecture as a proxy to articulate the unknown woman’s emotional state. By utilizing inanimate spatial forms, the author can express that even the protagonist’s inner thoughts, her psychological private space, have become detached and objectified in the same way that men perceive her as a person. Early in the chapter, she looks out onto the ‘cemetery of murdered daughters’, a space that ‘is large and dark, no, it’s a hall, with dirty walls […] there are no windows and no doors. My father has imprisoned me and I want to ask him what he intends to do with me but, again, I lack the courage.’ Though an emanation of her own trauma, she starts to notice details of the enclosure that entangle it with the Holocaust and gas chambers: ‘a black hose, hoses are fastened all around the walls, like gigantic leeches wanting to suck something from the inside’. All of this diminishes her claim on her own interiority as she shoulders her own burdens interwoven with those of German and Austrian postwar society, and there is no exit.

The father figure has a dual symbolic function in representing patriarchy and fascism: how collective regimes manifest themselves in individuals. It could be said that Malina defines patriarchy and fascism as systems that control the boundaries between physical and psychic spaces, that invade the private sphere and that instil their values in the subconscious.

The third and final chapter brings the narrator a moment of composure before the significance of its title, ‘Last Things’, becomes clear. Discussing the differences between men and women upon entering into relationships, the protagonist notes: ‘There are spasmodic rearrangements: a female must suddenly distance herself from everything and accustom herself to something entirely new.’ A man, on the other hand, ‘continues his habits in peace’. Men perform the role they desire; this remoulds the woman’s personal sphere. Coercion through affection follows, as she is forced to fit a particular mould: it’s by way of such enactments that she becomes ‘an unknown woman’, foreign even to herself. It appears there is no way forward, no chance of symbiosis between the two domains; she craves comfort and contentment through human relations, yet pays for it with the threshold between her mind and her actions being warped by male desires.

While the book explicates the boundary asymmetry between people, it also contains allusions to more literal thresholds. Doors, which are often associated with gaining privacy or shutting out the world, litter the novel, but they rarely operate properly. While battling the mirages of her father, the narrator delineates that ‘the doors have been taken off their hinges to prevent me from locking myself inside, my father laughs’ and ‘I want to and have to slam doors loudly, like my father always slammed all doors […] But the door clicks shut quietly, I am unable to slam it.’ Frequently, there is no way out or, when there is a door, either it doesn’t keep others out or it doesn’t function for her the way it does for men. Fundamentally, it is the existence of any rooms or gendered spheres at all that is dangerous, because it allows men to be in control of the thresholds between them. The narrator forms a utopian antithesis to this problem early in the novel, describing how she wishes people would traverse the world ‘as if there never were an open door, as if there never were a closed one, as if there weren’t any room at all, so as not to profane anything’. Appropriating architecture to express human relations, she evokes a place where there are no separations between people, no private spheres in which abuse and trauma can be hidden, no public spheres for men to dominate.

In the latter pages of the book, the unknown woman herself becomes the threshold between spheres and appears to initiate her own erasure as she dematerializes into the walls of the flat she shares with Malina. She becomes the liminal zone between inside and outside, public and private – even, perhaps, between male and female dichotomies: ‘I have walked over to the wall, I walk into the wall, holding my breath.’ It is only through her dispersal that she can be at the point of intersectional plurality, where things are constantly coming together, changing without ceasing to be themselves, rather than being pulled apart and categorized. Here she can be the threshold and be in control of it.

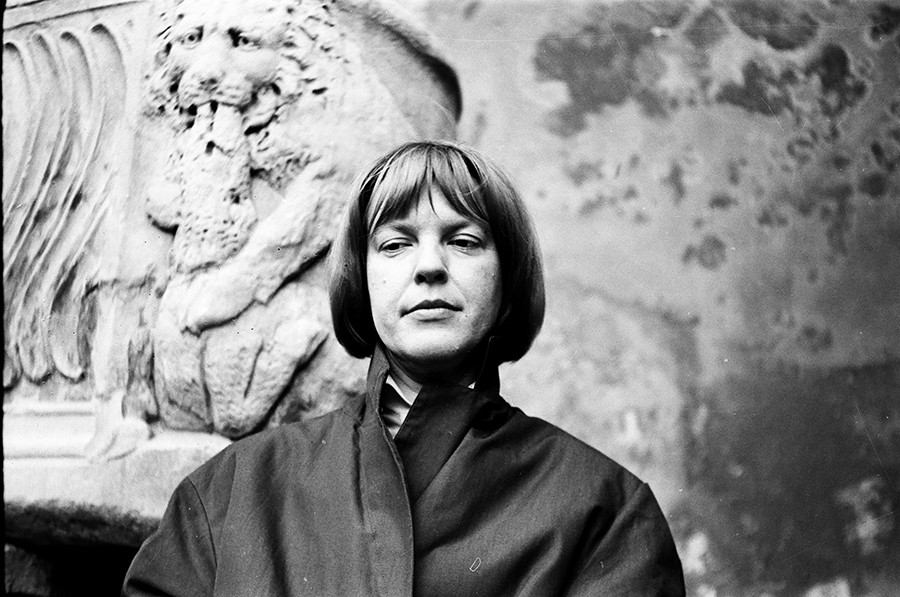

Main image: Ingeborg Bachmann. Courtesy: New Directions; photograph: Heinz Bachmann