Around Town

Brussels, Belgium

Brussels, Belgium

‘Have you been half asleep? And have you heard voices? I’ve heard them calling my name; is this the sweet sound that called the young sailors? The voice might be one and the same.’ This oneiric quote is carved into the trunk of a pale aspen in Afterglow (2015), one of Sean Landers’s three nocturnal paintings (at Rodolphe Janssen) of trees etched with quotes, song lyrics and jokes. The inscriptions suggest that existential struggles are, if not universal, at least shared by this artist and his eminent sources. Other quotes come from canonical poets Robert Frost and Anne Sexton, but any sense of grandiose literary references is punctured by the realization that the verse quoted above is from Kermit the Frog. Landers’s exhibition is one of several concurrent painting shows in Brussels, capital of a region with a centuries-old painting tradition that still provides artists with inspiration.

An adjacent room at the gallery displays six paintings of wild animals whose coats bear distinctive tartan patterns rendered in Landers’s tiny brushstrokes. Most of the noble animals – including elk, musk ox and caribou – are indigenous to North America, painted life-size in their natural habitats. The works could reference current debates around climate change, were it not for Landers’s mapping of the human organizing principle of clan markings onto the animals’ fur. The press release explains that these plaid creatures are Landers’s tribute to Belgian surrealist René Magritte’s ‘Période Vache’ (Cow Period, 1948), a series of around 30 ‘bad’ paintings, in which Magritte swapped the wry refinement of his earlier work for a grotesque caricature of his own style. (Meant as a challenge to the genteel dominance of the Parisian art market, the project was a commercial and critical flop.) But I couldn’t help but wonder about the extent to which Landers’s pleasing pictures of animals set in chocolate-box landscapes actually honour Magritte’s ‘Vache’ works. Wouldn’t it have been a more mordant tribute for Landers to paint something that was repulsive and unsellable, as Magritte’s paintings proved to be?

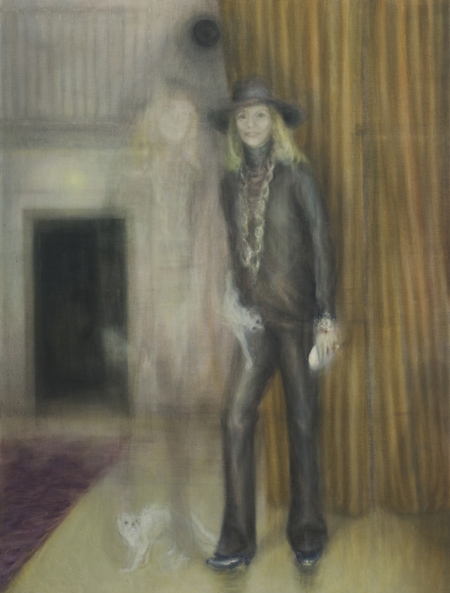

At Albert Baronian, one of Brussels’s first contemporary art galleries, established in 1973, the young Belgian artist Helmut Stallaerts also taps into Magritte’s legacy: in a portrait of Anne-Marie Gillion Crowet, a Belgian collector who modelled for the surrealist master – notably for La fée ignorante (The Ignorant Fairy, 1956), in which a candle casts a dark shadow onto the exposed side of her face. She is still recognizable in Stallaerts’s painting Der Auftrag 2 (Portrait of Gillion Crowet) (2015), thanks to her shoulder-length blonde hair, topped with a felt hat, but her image seems painted after a dream or an eroded memory. Stallaerts depicts her caught mid-step, with an emaciated white cat clinging to her hip. The composition is ruled by a series of vertical lines that seem to flicker like neon tubes. A mirrored, ghostly version of the subject appears on her right, this time with a translucent cat on the ground.

Optical effects abound in Stallaerts’s paintings. Sometimes they result from his use of wax and oil on leather, which softens the image into a haze of ambiguity; sometimes they arise through framing and perspective. The Boardroom (2015) depicts a large conference table set with water, glasses and manila folders extending at a sharp angle into the distance, where it is presided over by a black monitor on the wall. At first glance, the room seemed empty, but a moment later I noticed a faint seated figure with his head in his hands, acting out a silent cry. Stallaerts’s technique has a gaseous quality that recalls the lamp-lit impressions of Belgian symbolist painter Fernand Khnopff or Francis Bacon’s Pope Innocent X (1953), a portrait also distinguished by its intense vertical lines.

At Hopstreet Gallery, the work of Tinus Vermeersch, a young Belgian painter descended from three generations of artists, recalls a Flemish pastoral landscape tradition in which the occasional strangeness found in Brueghel’s paintings is distilled into pared-down scenes. Working in oil on board, Vermeersch begins with a gesso ground, whose imprimatura shows through multiple layers of translucent oil paint as vertical lines dragged by his brush, producing a texture resembling rays of light. The most common form in his repertoire is a wig-like shapewith matted locks he calls ‘tegumen’, after the Latin word for ‘covering’ or ‘protection’. Reminiscent of carwash brushes, the organic form first featured in Vermeersch’s work in 2010 and has since reappeared in various sizes and materials, including plaster and bronze.

The tegumen features in the new dreamlike works here (all Untitled, 2015), where it manifests in one painting as a shape resembling a haystack and in another as a sort of dreadlocked cocoon from which a pair of human legs protrude. Elsewhere, green brushstrokes coalesce to form a bulky torso topped by a loosely painted oval, less a distinct face than a pareidolic arrangement of brushstrokes. The works hang on walls painted in faded khaki and gold-green, which set off the rich vermillion and red lake pigment in several paintings. A pair of brown ink drawings in an adjacent room act as studies of the tegumen’s structure: a mesh frame with locks of hair tied at regular intervals. It’s a painstaking analysis of this recurring motif, recalling the precision of the strange bestiary found in the works of early Flemish masters such as Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. From Landers’s tartan beasts to Stallaerts’s skeletal cats and Vermeersch’s tegumen, a network of painted chimera forms across the city.