The Unsettling Presence of Francis Bacon

A packed survey at the National Portrait Gallery in London reveals an artist who was the architect of his own myth

A packed survey at the National Portrait Gallery in London reveals an artist who was the architect of his own myth

Francis Bacon’s beady eyes – the first thing visitors encounter in this comprehensive survey of the artist’s portraiture at London’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG) – exert an influence that permeates the entire exhibition. The painter, then aged 59, stares out like an inquisitive bird in a clip from Peter Gidal’s black and white film Heads (1969).

Here is an artist seemingly aware of his self-image and myth, sitting for an intimate filmic portrait so close-cropped you can’t see his ears. ‘Human Presence’ is the title of this show, yet it is undoubtedly Bacon’s presence that is felt most intently throughout the two burgundy corridors and several adjoining galleries that contain more than 55 works.

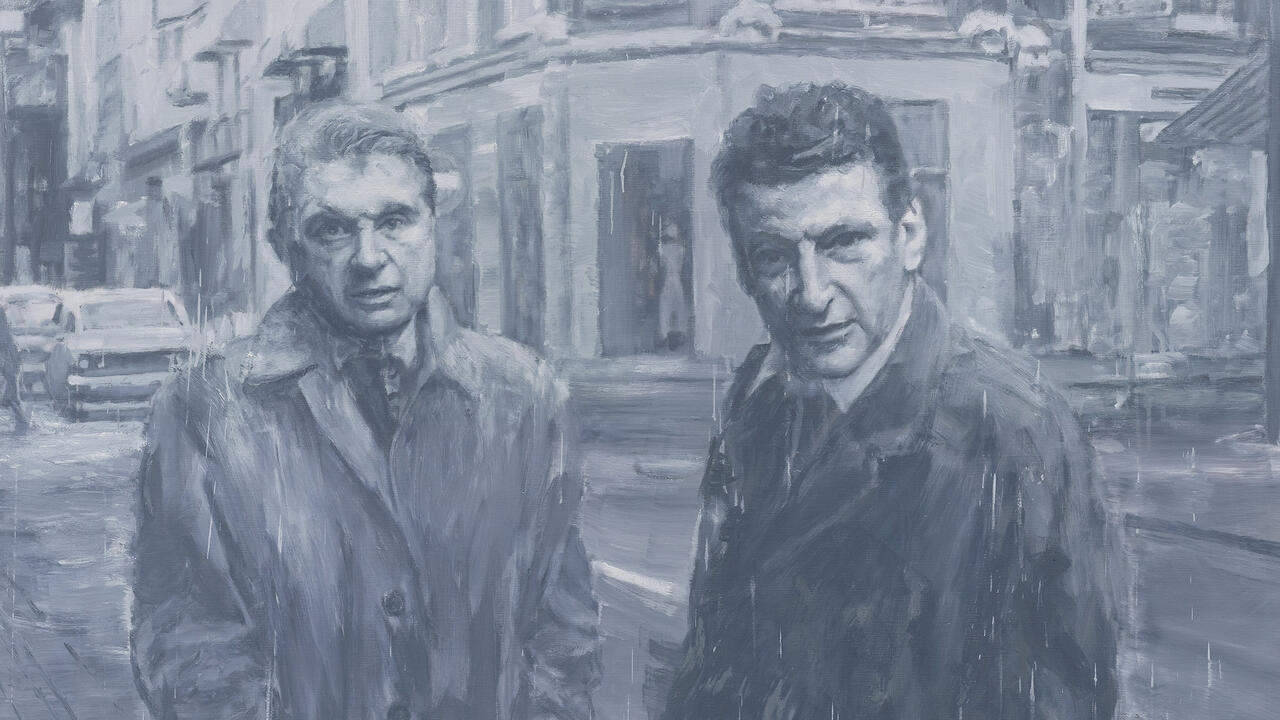

The ambitious scope of the exhibition feels too great for the confines of the space, which is how I also felt about the artist’s survey at Tate Britain in 2008. Two masterpieces bookend the show: the first is Head VI (1949), his early atomic depiction of an isolated, distraught Pope, which over the years you may have seen reduced to prints on tea towels and mugs; the second is Triptych, May–June 1973 (1973), a trio of canvases portraying the final moments of Bacon’s most storied lover, George Dyer, a small-time gangster who died from an overdose in a Paris hotel room in 1971.

Not all of Bacon’s paintings were as profoundly stirring and synthesized as these two monolithic works, but those that are contain some of the 20th century’s most majestic passages of paint. The exhibition’s thesis focuses on how Bacon’s attention to his subjects developed over time and revolutionized his approach. It traces his journey from early renderings from life to reworkings of the historical masters he so admired (Vincent van Gogh, Diego Velázquez et al.) to paintings from photographs of his muses, often friends and lovers, those flawed and maverick individuals of The Colony Room Club and Wheeler’s Oyster Bar.

I often see contemporary queer painters portray their community as if in a chic, A24 film of their life. Bacon didn’t; in Henrietta Moraes (1966), the titular artist and muse is a totemic swirl of emotions, hemmed in by a green outline that subtly alters in tone as it trains the figure’s fixed circumference. Reclining on the beige, striped daybed, she paradoxically towers before us, an animalistic vision with an almost-obliterated face. Moraes was his most emphatic subject.

An interpretation panel near the beginning of the show will have you believe that Bacon’s interior fixtures are often ‘incongruous’ to his figures, which are the central focus. I disagree: the door handles, soft furnishings and porcelain toilet basins are essential in engendering the overall unease of a composition. The suggestion being that, while the home purports to be comforting, for some it contains insidious disquiet.

What happens when, through historicization, a character whom society might consider unsavoury must become universal?

A detailed queer reading of Bacon’s work is often lacking in institutional exhibition panels, particularly concerning normative structures, such as the conventional home, alternative formulations of friendship and fringe sexual practices. What happens when, through historicization, a character whom society might consider unsavoury must become universal? But there’s plenty here that is universal: the relatable horrors and responsibilities of being inside a body.

Take a moment to consider the meeting of colours in the garments of Bacon’s Homage to Van Gogh (1960), a re-working of the Dutch artist’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889) – familiar blood-red rubs against two shades of emerald in a stunning example of his masterful palette. Nearby, he takes on Van Gogh’s The Painter on the Road to Tarascon (1888), a lost work in which the figure of an artist jauntily sets out with an easel and canvas to paint en plein air. In Bacon’s version, the shadow that stretches beside the feet of Van Gogh’s painter has swallowed him whole.

In an adjoining room, a wall of photographic portraits tracks his personal evolution from a cherub-like boy (Francis Gutmann’s Francis Bacon, 1933) to a pensive artist (Sam Hunter’s Francis Bacon at Cromwell Place, 1950). He loved the camera, and it loved him. Turn 180 degrees, and an unexpected face will greet you: Rembrandt van Rijn’s quizzical Self-Portrait with Beret (1659). It’s a delightful curatorial touch in an unassuming place that ratifies the lineage within which Bacon was operating.

Bacon’s portraits from life, such as Study for a Portrait of Lisa (1959), are his most lifeless; he specialized in once-removed depictions gleaned from an encyclopaedia of so-called working documents, some of which appear here in the form of paint-splattered clippings. There are also some lesser-known gems, which set this show apart from those I’ve seen before, including Three Studies of Isabel Rawsthorne (1967), in which separate portraits of Rawsthorne disconcertingly scatter across a domestic scene. When Bacon trains the brush on himself, the results are intentionally bashful, as in Study for Self-Portrait (1963), in which his awkward limbs disappear into his lap like it’s a plughole.

Before I entered the exhibition, the ‘presence’ of its title struck me as a curious rubric for Bacon, particularly since many of his earlier figures appear deliberately locked away from us in their own personal chambers. I more vividly associate this notion of connectivity with his contemporaries, such as Alberto Giacometti, whose spindly bronze men bound into our world. However, there is something enduringly present in Bacon’s sensibility, which invites us to confront our most carnal desires and fears.

Bacon’s lore is strong, and I leave this fascinating show reflecting on how much of it he cultivated himself during his lifetime. His style undoubtedly softened with age. Eighteen years after Gidal’s penetrating film, Bacon, aged 78, painted Self-Portrait (1987), in which his eyelids seem heavy. At first, it felt like a strange curatorial choice to situate this small canvas so close to the entrance of an almost-chronological show. But, by the end, it made total sense. The artist had come full circle: from screaming into the unyielding abyss to a more serene, haunting presence.

‘Human Presence’, a survey of Francis Bacon’s portraits, is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, until 19 January

Main image: J.S. Lewinski, Francis Bacon (detail), 1967, photograph. Courtesy: © The Lewinski Archive at Chatsworth / Bridgeman Images.