Artist Project: Barbara Bloom

Since the 1970s Barbara Bloom has used photography, installation, film and books as a means of looking at issues of collecting, museology, design, taste and our investment in the objects with which we surround ourselves. In this project for frieze, created together with writer Susan Tallman, Bloom – who is referred to throughout as ‘BB’ – presents selections from her 2008 installation and book The Collections of Barbara Bloom, a work about ‘the way things carry ideas’

Since the 1970s Barbara Bloom has used photography, installation, film and books as a means of looking at issues of collecting, museology, design, taste and our investment in the objects with which we surround ourselves. In this project for frieze, created together with writer Susan Tallman, Bloom – who is referred to throughout as ‘BB’ – presents selections from her 2008 installation and book The Collections of Barbara Bloom, a work about ‘the way things carry ideas’

The Collections of Barbara Bloom

The Collections of Barbara Bloom (2008) is an installation and artist’s book masquerading as a retrospective and catalogue raisonné. Or the other way round. Inspired by the estate auctions of Jackie O and Andy Warhol, with their peculiar amalgams of biography, fetishism, pathos and marketing, Barbara Bloom (BB) decided to organize a historical self-portrait, an array of objects (art works, photographs, furniture, and tabletop whatnots) that would give physical presence to the thoughts that have occupied her throughout her career. Many of those thoughts are about presence, absence and how physical things are entrusted to fill the lacunae of our lives. So the ideas carried by bb’s things are largely about the way things carry ideas. She likes the mental and visual hopscotch that occurs when ideas stand in for people and things stand in for ideas.

The 11 chapters, or departments, of this endeavour are necessarily allusive: ‘Innuendo’ is the first, ‘Songs’ is the last. The project as a whole forms a kind of solipsistic symphony in which certain material motifs appear and reappear in call and response, sets and variations. We find glassware, chairs, statuary, chairs, carpets, chairs. Chairs that stand (or sit) for particular people, chairs that stand for events, chairs that stand for sins, chairs that stand for whole cosmologies.

The three chairs shown above belong to The Reign of Narcissism (1989), an installation that takes the apparent form of an octagonal period room. The precise period in question, however, is vague: restrained, elegant, but just a titch too fussy, the room suggests a kind of cross-Channel, cross-dressing hybrid of an Ancien Régime lady’s boudoir and a Regency gentleman’s library. The entrances are flanked by plaster busts of the artist and the crown moldings are ornamented with her profile; the four glass vitrines that lined the walls displayed 30 leather-bound volumes of BB’s ‘Collected Works’, as well as three potential tombstone designs (‘She lived for beauty…’) and boxes of chocolates embossed with her silhouette. Her face glows from the bottom of porcelain teacups and on the surface of hand-carved cameos. Like everything else in the room, the chairs that were set around the periphery are serenely, coyly, and obnoxiously about BB herself. The chair on the left is upholstered in a pattern of her signature, the one on the right with her horoscope, the one in the center with her dental X-rays.

Not surprisingly, the dental X-rays make for the least ornamental of the patterns – from a distance they look like little more than regular ink smudges – and they are also the funniest and most disturbing. Teeth, we know, are often the only things left behind when the recognizable body and soul have disappeared, and dental charts are commonly associated with last-ditch forensic efforts to identify bodies. Their peculiar pathos derives from the fact that, however useful they are at identifying, they are profoundly powerless to evoke the person in question. A portrait, a memoir, the empty chair by the fire might do the job, but a dental X-ray can only suggest a void.

BB really does like the mental and visual hopscotch that occurs when ideas stand in for people and things stand in for ideas. Perhaps because she knows it’s a fraud.

Barbara Bloom Belief in Style 1986, c-type print and Modernist Confession 1986, Gerrit Rietveld, Red Blue Chair, framed photograph mounted on board, cut and inset with photographs of Piet Mondrian’s studio, red roller-blind.

Belief

In the mid-1980s BB was asked to do a project with the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague, which is proud possessor of an extensive furniture collection that is especially strong in Dutch Modernism. BB has always been suspicious of the authority implicit in ‘good’ design – the way things just seem more credible, more spiritually and intellectually fit, if they adhere to certain visual rules. Her poster for the event bore the motto ‘Belief in Style’ – in no-nonsense mid-century sans-serif – sandwiched between a quadriga of Modernist chairs at bottom, and a ruined church filled with rows of folding chairs. The words – all caps, linear, professional – tied together the sacred (high Modernism and Gothic arches) and the profane (home accessories and a great place for a wedding).

Inside the museum she played upon religious confessional form, pairing Gerrit Rietveld’s iconic Red Blue Chair of 1918 with a photograph of a Shaker interior (amazing grace, how sweet that chair) amended with bits of Piet Mondrian’s painting studio; a red roller-blind acts as the curtain screening penitent from priest (though which is which is anyone’s guess). The Shakers were straightforward about the religiosity of their manufacture, high Modernists less so. It has taken a few generations to see the Rietveld chair not just as a breakthrough into bold formal experimentalism, but as an argument for the moral rectitude of rectilinear forms, a Calvinist hymn with footstool. People have often preferred extreme settings for the exposure and expiation of sin: mountain tops, deserts, dark closets and hard benches, places that promise, like Rietveld’s chair, to marry the virtues of the aesthetic and the ascetic, enlightenment and bruised backsides. Confession, after all, is not supposed to be comfortable. Nor is it supposed to induce smug self-satisfaction, though it very often does.

Rietveld’s wooden slabs, like the poster’s sans-serif clarity, speak of progressive thought and responsible living, emancipation from tormented ornament and neurotic nostalgia. They evoke a world now lost to most of us – a world in which people actually believed in design as something more than just style: design as politics, design as salvation. ‘Style’ implies the meanness and ephemerality of ‘taste’, whilst ‘design’ suggests the infinite grandeur that is ‘faith.’ Henri Matisse, painting away in the south of France, famously aspired to make art that would act like a comfy chair (un bon fauteuil qui delasse ses fatiques physiques – an easy chair that relieves fatigue), but Calvin’s line was Finitum non est capax infiniti – the infinite cannot be held by the finite.

It’s a lot of weight to put on a chair.

Bentwood chairs by Michael Thonet in the permanent collection of MAK, Vienna. Exhibition design by Barbara Bloom, including translucent walls, lights, photo frieze and screenprinted text labels, 1994

Shadow Play

The bentwood chairs of Michael Thonet (1796–1871) and his sons are familiar avatars of fin-de-siècle Vienna: the repressed yet sociable curves of the ubiquitous café chair, the louche extravagance of the rocker with its ardent calligraphic loops, the dour caning that looks like cinched corsets, all suggest the fossilized bones of a time and place most often evoked through the spineless metaphor of whipped cream.

In the early 1990s BB was asked to design a display for the dozens of Thonet chairs belonging to Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts/Contemporary Art (MAK). Decorative arts museums are often torn between the desire to present their holdings instructively and categorically, and the desire to use their things to recreate the experience of a vanished world. One strategy carries the dusty scent of the academy, the other reeks of the heritage theme park. With objects as emblematic of a time and place as Thonet chairs on display in a museum in Vienna, the difficulty is acute. BB chose to play with the chairs’ emblematic status itself.

One surefire indicator of whether an object has achieved the status of an emblem is the degree to which it can be recognized in silhouette (hence the brilliance of the iPod advertising campaign, which created a recognizable emblem almost before there was a product). BB lined a gallery with the chairs along two walls, but placed them behind gauze scrims so that all one sees are their shadows, projected and hovering – a corridor of bentwood ghosts.

Thonet had been both a sophisticated designer and a forward-looking businessman, employing an assembly line, advertising, and catalogue distribution, but in one respect his products retained the dry taxonomic character of the previous century: his famous café chair – the one generally brought to mind by the words ‘Thonet chair’ – was simply identified by him as Chair no. 14. bb brought Thonet into the age of Ikea by giving each of his designs a name – Diotima, Sigmund, Ludwig – each derived from an emblematic Viennese fin-de-siècle source: Robert Musil, Sigmund Freud, Karl Kraus, and so on. The name labels the shadow, which stands in for the chair, which evokes a time, but it’s all smoke and mirrors, scrim and bent wood.

Barbara Bloom. Homage to J.-L. Godard, 1986, unfurled roll of yellow backdrop paper, bentwood café chair, wall paint, framed photograph by F.C. Gundlach, Jean-Luc Godard while representing his first movie À bout de souffle (1961)

Breathless

BB is hardly the first artist to have conceived of chairs as stand-ins for people. Vincent van Gogh’s paired portraits of his chair and Paul Gauguin’s are perhaps the most famous, while Sir Samuel Luke Fildes’ post-mortem watercolour of Charles Dickens’ empty writing chair is perhaps the most maudlin. (Dickens himself, of course, used Tiny Tim’s ‘vacant seat […] in the poor chimney corner, and a crutch without an owner’ to impressive, tear-jerking effect.) BB is not so much interested in the expressive treatment of a banal subject as she is in the logic of the metonym, the standing in of one thing for another: the object for the person, the seat for the body, the presence for the absence.

In the 1980s BB had already made a few portrait ‘homages’ – each composed of a picture, rolls of photographic backdrop paper, and a chair – when, one day in Berlin, she stopped in at a photography exhibition and saw F.C. Gundlach’s 1961 portrait of Jean-Luc Godard, seated on a bentwood chair, in front of an unfurled roll of photographic backdrop paper. The photograph is framed so that the backdrop paper is clearly revealed for what it is, functioning, as in BB’s pieces, to isolate the subject while revealing the complete artificiality of the arrangement. As a device, it paralleled Godard’s own filmic devices.

Godard had long been one of BB’s personal heroes – her first homage piece had, in fact, been a response to the death of Jean Seberg, the gamine ingénue of Godard’s 1960 film À bout de souffle (Breathless). BB loved the way films such as À bout de souffle skirted the hackneyed interior voice; the way that everything important was communicated elliptically, and objects were allowed to speak for themselves. She loved Godard’s refusal to fill in the blanks, exposing instead an abandoned ground scattered with clues.

There was nothing else for her to do: she bought the photograph and hung it on a painted rectangle, beside a matching, unfurled roll of photographic backdrop paper, with a bentwood chair standing on it.

In a coda that Godard would no doubt have rejected as too coy for fiction, BB’s Homage to J.-L. Godard (1986) was being shown at an exhibition in Europe when Gundlach came through. Gundlach, it turns out, is a serious collector himself.

He bought the piece.

Barbara Bloom Pride from ‘The Seven Deadly Sins’, 1987, framed photograph in velvet mount, molded plywood Lounge Chair Metal by Charles and Ray Eames, calling card engraved with the word ‘pride’ on seat

Pride

There are seven deadly sins in all, and in a series of works from 1987 BB gave each of them a seat and a setting: Rage, in the form of an etched perfume bottle, rested on a small velvet stool in front of a picture of Freud’s couch; Sloth, a circled word in a copy of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), lounged in a slung-canvas deck chair by a beach scene; while Envy, embroidered on a handkerchief, was dropped onto just one of a matching pair of gilt chairs facing off in a corner. As is her usual practice, in each case BB sought out the most economical way to carry the allusion – there is no point to invest in authentic 18th-century fauteuils when the important thing is not their provenance but their twinned appearance of anxious pretension. At least that was her practice until she got to Pride.

Pride alone is the real thing: a mint condition Eames Lounge Chair Metal (‘LCM’ to those who like to be on a nickname basis with furniture) from the late 1940s. In point of fact, BB set out to purchase the most expensive example she could find. The chair sits regally before a framed silhouette portrait of itself, and on its revolutionary molded plywood seat rests a calling card for the sin itself.

The Eames LCM is still in production, as it happens, and new ones can be had online for US $429–529 a pop. But with Pride, physical appearance – sleek organic curves and visual rigor – are only a piece of the point. Pride rests not only on the self-conscious sophistication of its tastes (one Kentucky-based vendor of the LCM actually goes under the name Highbrow Furniture), but also on the exclusivity of its pedigree. That visible curvaceous rigour is allied to a body of knowledge (or at least belief) that is largely invisible – not just any LCM, but an original LCM, a mint LCM, an LCM with provenance and a piece of paper to prove it. Knowing that, we can be expected to see it differently. It is a point that has preoccupied BB before: to what degree do we see what we believe, and not the other way around.

Scientifically-minded people will sometimes point, disapprovingly, to the fickleness of aesthetic response, the way that authentic pictures are declared to be more beautiful than fakes, even when they were actually the same object until some fresh art historian came along and changed the attribution. Those who use this fact (which is true, of course) to reduce a love of art to mere social pretension, should take note of a recent study at Duke University, North Carolina, comparing the effectiveness of placebos that cost ten cents with ones that cost two dollars and 50 cents. Both pills were empty poseurs pretending to be real medicines. Nevertheless, the expensive ones worked better.

Belief in style, anyone?

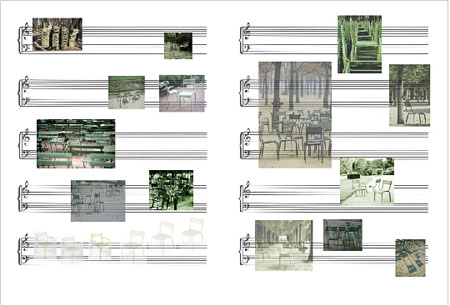

Barbara Bloom Luxembourg Garden Chair Song 2008, magazine page 99 in frieze, April 2011

Tête à Tête, Chaise à Chaise

What is it about the scattered chairs of the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris that seems to distill the very essence of civilization? BB, I think, was drawn to the suggestive sociability of the arrangements in which one finds them, as if like children’s toys, they move about after dark, have their little parties, conversations, romances and spats, only to freeze the moment wakened eyes fall their way. Their song is polyphonic, an array of independent lines, moving in and out of harmony, sharing a common cultural purpose offset by discreet personal agendas.

Like the Eames Lounge Chair Metal, the chairs in the Luxembourg Gardens can be bought and put in your own private garden for a bit of Gallic sophistication. But even if you were to buy a group of them – a couple, a ménage à trois, a more extended Mitterand-style arrangement – it would rather be missing the point. The Luxembourg Garden is not a private retreat, but a great and public space. The lyricism of the chairs erupts, not from any individual genius, but from the serendipitous wisdom of countless strangers. Americans in particular find it remarkable is that anything not privately owned could be so pleasant, so well-maintained, so … desirable.

Day after day the chairs are there. Paris is not Paradise; some chairs must get nicked, and some of them must get nicks, but somehow most remain, silent witnesses to shifting ententes, silent embodiments of an ideal, silent notes in a song.

Barbara Bloom is an artist who lives in New York, USA. She has recently finished a series of works titled ‘Present’, which focuses on the similarities and differences between the practices of making and viewing art, and the practices of giving and receiving gifts. ‘Present’ is on show until 15 May at Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan, Italy.