Barbara Chase-Riboud Looks at the World Askance

The artist speaks with Terence Trouillot about how her art and writing have finally met

The artist speaks with Terence Trouillot about how her art and writing have finally met

Terence Trouillot You have two large survey shows this autumn: ‘Monumentale: The Bronzes’, which opened last month at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, and ‘Folds of the Soul’, which opens this month at Serpentine North Gallery in London. Can you tell me a little about both shows and how they will differ in theme and scope?

Barbara Chase-Riboud It’s actually an astounding coincidence that these two shows are happening back to back. On top of that, my memoir, I Always Knew [Princeton Press, 2022], is coming out in October, which also was a surprise. So, these three things are converging in what is going to be an epic journey, like the film Ben-Hur [1959], because we’re truly going from 1958 all the way to 2022.

TT In ‘Monumentale: The Bronzes’, there’s a through-line from some of your earliest works to some of your most recent. Will there be a similar framework to the Serpentine’s show?

BCR They’re totally different but there is some crossover. What’s interesting is the way one picks up off the other. So, for instance, both the Pulitzer Arts Foundation and Serpentine will have a few sculptural works dating back to the early 1970s from the series ‘Malcolm X’ [1969–2017] – my tribute to the American civil-rights activist who was murdered in 1965. But the big news is that Josephine [2022] – my monument to the singer and dancer Josephine Baker – will be unveiled at Serpentine. Last November, Baker was inducted into the Panthéon – the French national tomb of heroes – as only the third woman in history, and the first ever Black woman, to receive such an honour. So, I decided that I would do a monument in homage to her.

TT You’ve led a fascinating life, emigrating from the US in 1957 and eventually settling in Europe. Along the way, you’ve travelled all over the world, including North Africa, China, Eastern Europe and Mongolia. Much of this is recounted in your new book of memoirs. Can speak to the genesis of that?

BCR The process of writing this book was practically unconscious. After the death of my mother in 1991, I found amongst her affairs a little dark-green tin box. When I opened it up, I realized that there were 600 or 700 letters that I had written to her from Europe, beginning in 1957: 34 years of letters to my mother.

At the time, I simply closed the box and said: ‘Not today and not tomorrow.’ It wasn’t until eight years later that I finally got someone to transcribe my letters. We put them in chronological order and I thought that, maybe, one day, there might be somebody who would be interested in publishing them. I shared the transcript with a few museum curators. Then, without my knowledge, Stephanie Weissberg, the curator of ‘Monumentale: The Bronzes’, sent the letters to Princeton University Press. She thought they were so extraordinary that they should be published. It is a work of love and also a work of intense emotion.

TT Can you talk a bit about that period in your life, particularly as a young woman travelling in Europe and Asia for the first time?

BCR Well, let’s put it this way: I was the first American woman to be invited to China after the revolution. I attended a dinner party with Chairman Mao Zedong.

TT Really? How was that?

BCR Me and 5,000 Chinese citizens. It was an extraordinary adventure. It was the apex of my adventures all over Africa, Eastern Europe and India. It was May Day and it was a sit-down banquet where they served 30 dishes! It was truly something to write home about, so I recounted the experience to my mother, which is in the memoir. I went everywhere because I was married at the time to Marc Riboud, a photographer and member of Magnum Photos, who covered the world. On many of these trips, I was just along for the ride. But what a ride it was! I discovered all kinds of new civilizations and new ways of looking at the world that I had no idea would ever come my way.

TT In addition to your work as a visual artist, you’re also an award-winning novelist and poet. I’m curious to know whether there’s any relationship between the two practices. Do you find that, sometimes, your writing informs your artwork or vice versa?

BCR For many years, I upheld the idea that there was no relationship between the literature and the art. People would ask me: ‘Do you get up in the morning and write a poem and then run downstairs to make a sculpture?’ No, it doesn’t work that way. Everything comes in waves. Everything comes in clusters. It’s only now, at the end of my career, that these two things are meeting together. So, we’ll see. The story isn’t finished yet.

TT There’s a wonderful vacillation between soft and hard in your sculptures, between the bronze elements – which are influenced by artists such as Alberto Giacometti – and the textile skirts that feature in the ‘Malcolm X’ steles. Can you describe how you arrived at this particular aesthetic?

BCR Giacometti was a great influence on my work in the 1960s. My first animal bone sculptures, such as Le Couple [1963], Tiberius’s Leap [1965], Sejanusand and Nostradamus [both 1966] were all surrealistic personages with legs. As the sculptures got more and more abstract, however, I became increasingly frustrated with the legs, which were interfering with the abstractionist mode. So, I had to get rid of them. I did this in the ‘Malcolm X’ series by making a curtain, a skirt.

The first work, Malcolm X #1 [1969], was a horizontal, floor-based piece. Malcolm X #3 [1969], however, rose straight up to become the first stele: its legs disappeared and there seemed to be a transformation of power from the bronze to the fabric and back again. The bronze looks like it is being held up – impossibly – by bundles of knotted silk. From then on, the series continued as steles. By this time, I had been to China and Cambodia, where I was inspired by funerary steles: large stone rectangular tablets, monoliths. Eventually, I was simply elaborating one from the other, experimenting with the size and the shape of the folds in the fabric. They became more and more baroque as I went on, in terms of both the silk and the bronze, so that there was an eternity of folding and pleating and knotting of the bronze.

TT To backtrack a little, you were famously the first Black woman to graduate from Yale School of Architecture and Design in 1960. What was that experience like?

BCR In the entire graduate school – not just the architecture school – there were only three Black women: one in philosophy, one in law and myself. The relationship between this powerful institution and these lone figures was very interesting, but I had already lived, worked and exhibited in Europe, so I came to academia with a different attitude. I also had a rather formidable reputation as Miss Chase. Everybody else was John or whatever, but I was Miss Chase. Nobody dared called me Barbie or Barbara. So, I had to assume that persona and do a lot of other things that most of the students didn’t have to.

I learned a great deal about a lot of things. About America, and so on. After I left Yale, I moved to London with the intention of living there. Then life interfered and I met my first husband, whose life was one of total internationalism. I did not really begin to do my own work until after my two children were born, so I had this hole in my career of seven or eight years. After I published my first novel, Sally Hemings [1979] – about an enslaved woman’s concubine relationship with US President Thomas Jefferson – the book’s success meant that my private life became public and I had to juggle two different professions at the same time, on top of having a young family. It was quite a challenge.

TT I was thinking about your series ‘Le Lit’ [The Bed, 1966], which comprises these beautiful charcoal and pencil drawings of two figures in bed that morph into these exquisite angular abstractions reminiscent of the shapes and forms in your bronze sculptures. I’ve always been curious as to whether those drawings were studies for your sculptures.

BCR I think that those designs are the bridge between the bone sculptures and the pure abstractions of the bronzes or the steles. They are the clue as to how the work evolved. Little by little, the bones became abstracted, and then transformed themselves into another kind of drawing. Because, if you look at the early, more figurative drawings from 1957 to 1970, they are really Giacometti-ish.

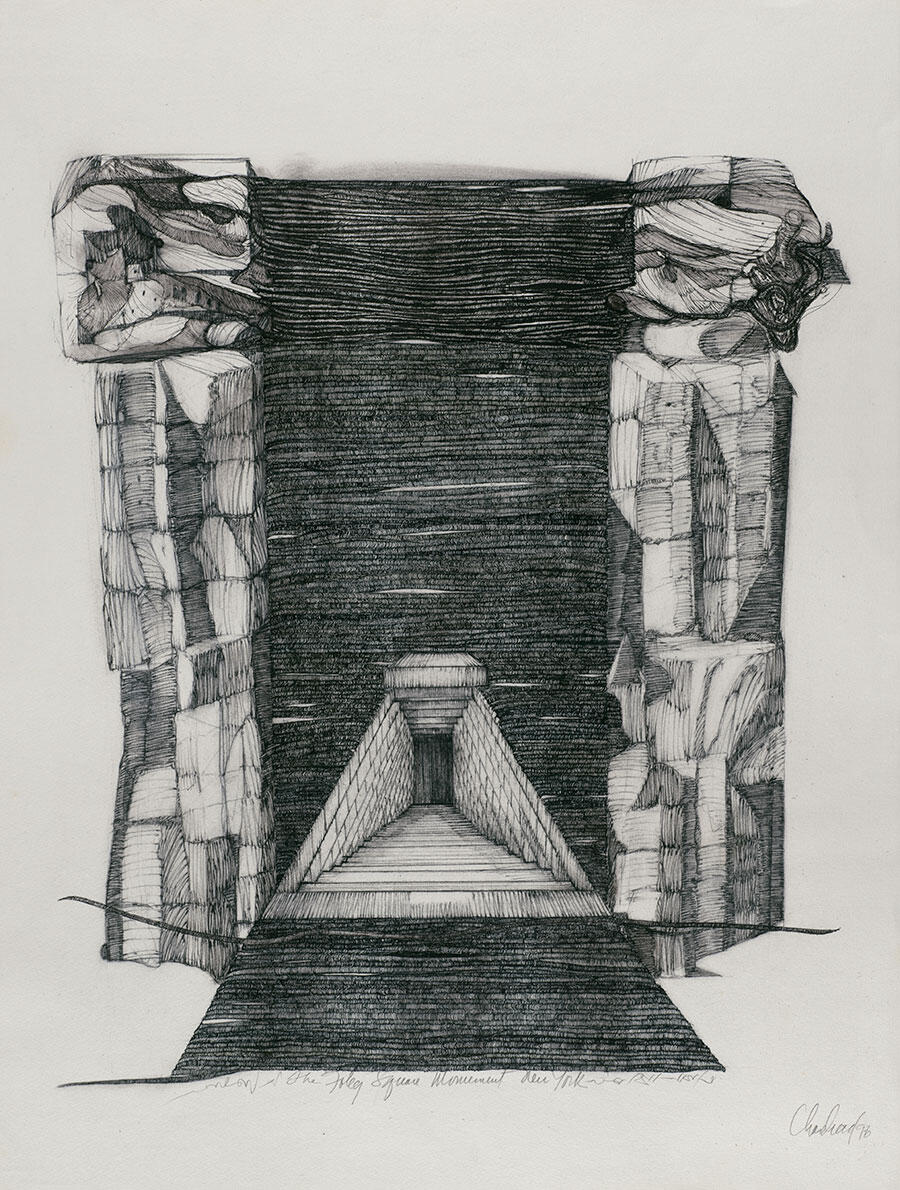

Once I had made that jump to skirts, and to manipulating the lines in an entirely different manner, I began working on another suite of drawings, the ‘Monument Drawings’ (1994–ongoing), which I have been developing for almost 30 years.

TT Are the ‘Monument Drawings’ preparatory works for your sculptures, in some respects?

BCR No, because I never make sketches for my sculptures. But I needed some kind of graphic frame for all these monuments to people who should have had monuments, but didn’t because of race or gender or whatever. The forgotten heroes. Those who will never have statues of themselves. For me, it was poetic; it was amazing.

And, of course, since these were works on paper, I didn’t have to worry about the architecture, about whether they would stand up or not. I have to decide whether that’s the end of the series or whether I’ll continue to make more.

TT What are you currently working on?

BCR Josephine is on the horizon. There are already two versions, but there’s going to be a third. I will know more when she finally sees the light because it’s an amazing transformation, turning Baker, who is all movement, into a stele, which is permanent and static. So, we’ll see where that goes. For me, she’s part of ‘La Musica’ [2022–ongoing] – a whole series of sculptures that have to do with music and movement and stillness. She fits in there, but she’s gone crazy. She’s going way, way beyond the ‘Malcolm X’ series. And so, there you are.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 230 with the headline ‘Interview: Barbara Chase-Riboud’.

Main image: Barbara Chase-Riboud in China, 1965. Courtesy: Serpentine Gallery, London