The Black Charismatic

Theaster Gates & The Black Monks of Mississippi’s latest project for IHME Festival, Helsinki

Theaster Gates & The Black Monks of Mississippi’s latest project for IHME Festival, Helsinki

Is listening the future of public art? Of politics? At its best, the work of Theaster Gates would seem to suggest so. Alongside a conceptual sculptural practice that listens to, and speaks of, Black history – charged, fetishized objects such as elongated shoe-shine stands, and reframed fire hoses formerly used as part of crowd control methods in Civil Rights marches – Gates has for the last decade reclaimed derelict spaces and turned them into areas of exchange in cities all over the world. It is a unique style of relational aesthetics. These spaces look like The Listening House in Chicago’s South Side, an archive of Black music in an area in which no one wanted to live (part of Dorchester Projects, 2009–ongoing). They look like a patchwork structure built inside of a ruined church in the UK city of Bristol, a ‘sacred space within a sacred space’, in which locals were invited to sing, dance and play instruments (Sanctum, 2015). Wherever it may be there is a strong scent of redemption and salvation in Gates’ work – a philosophy of imbuing broken things with life. This ‘spiritual ecstasy’ (as he calls it) is hinted at in The Black Charismatic: the title of a body of work commissioned by Helsinki’s IHME Contemporary Art Festival earlier this month.

A multifaceted presentation, The Black Charismatic encompassed a film premiere at Helsinki’s Finnkino Tennispalatsi cinema, a live performance at the Rock Church with The Black Monks of Mississippi, an in-conversation with Van Abbemuseum Director Charles Esche at Gloria Cultural Arena, as well as a film installation which can still be seen at the Finnish Salvation Army Temple. This quartet lay at the centre of a series of related festival events aiming to tackle themes emerging from Gates’ practice – film screenings inspired by found and discarded materials, and panel discussions tackling the value of art and cultural appropriation.

But what to review? As with Gates’ other commissions, The Black Charismatic is a Gesamtkunstwerk, its parts un-viewable in isolation without missing some key translation. A viewer unfamiliar with the artist’s portfolio would have had to search hard for context. Dedicated viewers had to take to the streets, hunting down all four components at their respective city-centre-based venues. Undoubtedly, the main spectacle was The Black Monks of Mississippi concert; set in a 1960s Lutheran church, hewn out of solid rock, replete with a glorious, circular, copper roof. It seemed like all of Helsinki had turned up. Stripped of Gates’ visual art and of any other contextual information, the performance felt bare and startlingly abstract. We were here to listen.

Describing The Black Monks of Mississippi as his ‘art-house band’ to Esche, the ensemble was originally formed in 2008 for an exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum. Nine years on, The Monks include Gates (who sings and ‘offers leadership around a conceptual framework’) and musicians Yaw Agyeman, Mikel Patrick Avery, Michael Drayton and Khari Lemuel. During the roughly 60-minute performance, one Monk skipped up and down at the back of the congregation ringing a bell, casting out spirits. Another Monk played deconstructed jazz trumpet; another played minimal piano keys. All slowly built up a cacophony of chants, wails, and broken harmonies that seemed to feel and test the space around them and us. Titbits of lyrics were woven together with restraint, barely recognizable from pop songs and hymns; from Parliament’s 1978 Aqua Boogie (‘I never learned to swim’), to Billie Holiday’s rendition of the protest song Strange Fruit (1939), to Amazing Grace. In the film premiere, Lemuel described his Monk status as ‘a spiritual path […] remaking myself and becoming less and less and having the experience less and less of having a self.’

Christian references abound in The Black Charismatic. Gates defined his dissected versions of evangelical singing, ‘loose utterances’ and speaking in tongues performed by The Monks and present within the film as a ‘language of youth’: a useful tool from his church-attending early years that could also be used to question the sacredness of space, and of the articulation of Black American history. As he sees it, architectural ruin signals societal ruin; the abandoned churches in South Chicago were the last, physical reminder that the 99% African American neighbourhood in which he lives had once been great.

However, at times The Black Charismatic felt forced, and some of the visual metaphors were in danger of veering into martyrdom. We probably could have done without footage of Gates standing under a leaking roof in an impromptu baptism. He clearly believes that good public art can rescue neighbourhoods. This culture-as-saviour model is, of course, highly problematic; ‘artwashing’ is now part of the political vocabulary. One questions the ownership, reach and permanence of such social impact, measured as it is by art world frameworks that includes Gates’ value in the art market. But in other, more subtle moments, namely the stripped-back live performance, Gates’ work can achieve transcendence. There is a power in this work that feels urgent given the terrifying politics of the current US administration. Certainly, Gates’ South Chicago community is never far from his practice regardless of which city he is exhibiting in. Back home, he works with people that have been prematurely discarded and actively forgotten; he teaches his community to mobilize using the tools of art and culture. Gates is also using his art world status to make others listen, in cities that have their own problems with historic suffering, long-term poverty, and gentrification.

Which brings us to Helsinki. Why here and why now? Finland is celebrating 100 years of independence in 2017, and issues both home and abroad are coming into sharp relief against the backdrop of a (relatively recent) turbulent past. Perhaps IHME’s organizers invited Gates to start a conversation about how to listen more effectively. Perhaps because of its northerly location nestled in-between Sweden and Russia, historically Finland has never been thought of as a culturally diverse nation (though that assumption has been challenged). And though immigration levels remain some of the lowest in the European Union, the rising numbers are causing increased racial tension. Its centenary programme (‘Suomi Finland 100’, run by the Prime Minister’s Office) includes events promoting tolerance; its website notes candidly how the majority of complaints received by the Non-Discrimination Ombudsman relate to ethnic origin. During my visit, asylum seekers were camping in the central Railway Square to protest the deportation system, and were being threatened by far-right groups. The adjacent National Theatre and Ateneum Art Museum had both been supporting the camp with facilities and resources; the Ateneum displayed a huge ‘Refugees Welcome’ banner depicting Europe cut off from the rest of the world with an ugly red line. Can you imagine this response from a major arts institution happening in the US, or in Britain? Given the context, IHME and Gates may be asking us all to listen more actively.

The 2017 IHME Contemporary Art Festival ran from 5-8 April. Theaster Gates’ video installation continues at Finnish Salvation Army Temple, Uudenmaankatu 40, 00121 Helsinki, until 29 April 2017. Admission is free.

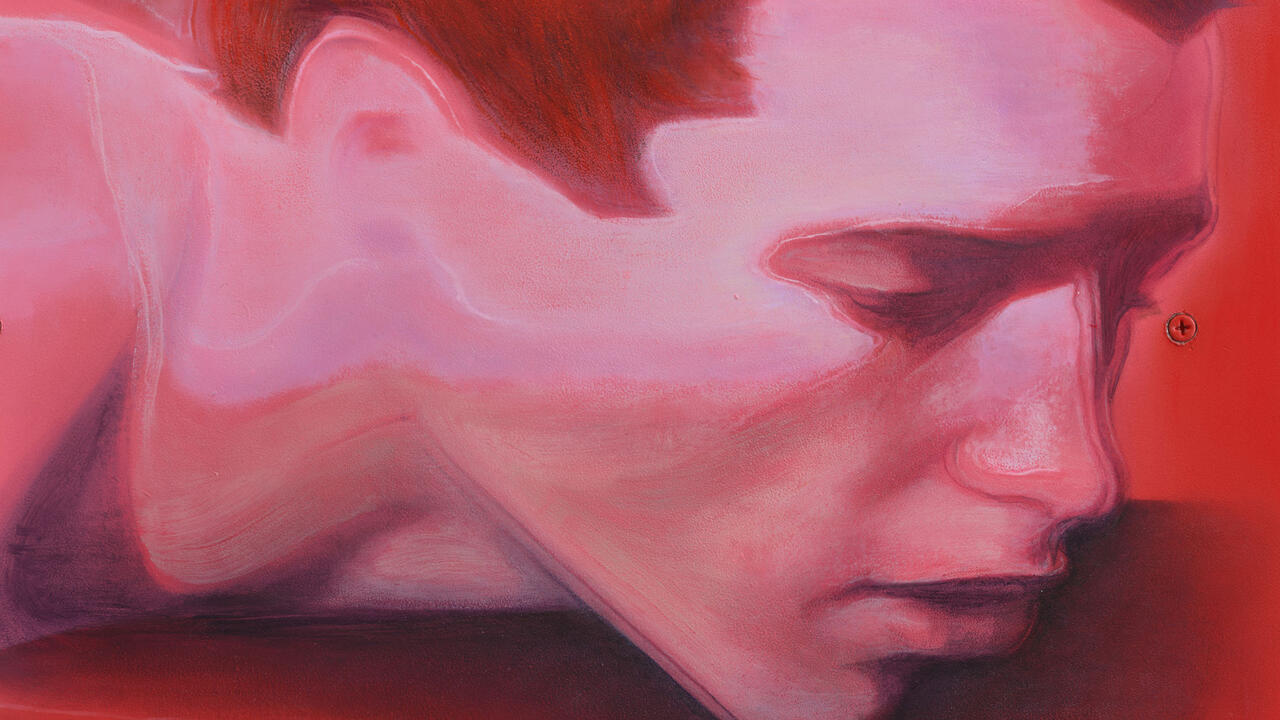

Main image: Theaster Gates and The Black Monks of Mississippi performing at St. Laurence Church, Chicago, during the building’s demolition, 2014. Courtesy: the artist, White Cube and Regen Projects, Los Angeles; photograph: Sara Pooley