Books

Gilda Williams’s new book on how to write about contemporary art

Gilda Williams’s new book on how to write about contemporary art

Let’s assume there is a crisis in art writing. The past decade saw a number of essays, books, panel discussions and events debating the state of criticism, the death of the critic and the demise of art publishing. So, let’s imagine that crisis: reviews always simply describe what is on view rather than say anything about it; catalogue essays never produce new knowledge, only serve to promote an artist’s market value; and the language of press releases, so often derided as hollow, has taken over. All those roundtables that bring critics back from the dead and onto the podium reflect a growing anxiety over the communicative possibilities of writing.

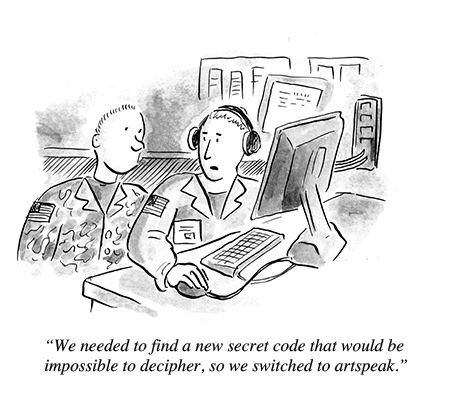

Gilda Williams worries about all of the above. Call it by any name – her slightly derogatory ‘art-patois’, mystical ‘speaking in tongues’, or plain old ‘artspeak’ – it’s all barely comprehensible to Williams. She sets out to correct this problem in a new book, How to Write About Contemporary Art (published by Thames & Hudson) which is structured to untangle the linguistic mess we have supposedly got ourselves into. In countless bullet points, she describes the field, its key players and its particular penchants (citing, amongst other things, a number of frieze articles), and then moves on to discuss style, the work of pitching and the different forms of writing in the contemporary-art context. Williams’s methodology is flawless. She brings in some 50 examples of texts, ranging from exhibition reviews to snippets of catalogue essays and artist statements, and attentively analyzes them. She highlights the use of active verbs, points out specific nouns, deconstructs complex grammatical structures and, all in all, seems to read these samples more closely than anyone has done before. In confident style – ‘Unless discussing a certain shark floating in a tank, or that porcelain bathroom fixture signed “R. Mutt”, never assume your reader remembers or has seen the art’ – Williams stresses that the essential approach to writing about art should be to answer three questions, easily summed up: (1) What is it? (2) What might this mean? and (3) So what? This formula is meant to answer what Williams sees as the inherent paradox of writing about art – ‘stabilizing art through language risks killing what makes art worth writing about in the first place’ – but her three-ingredient recipe is not a solution, it’s a formula so simple that it could work just as well for nutritionists as it could for contemporary art writers. (Quinoa: a popular supergrain that can be eaten in salads, soup and stews; this may lead to a food shortage in Bolivia, but it provides a good source of protein for westerners.)

The book has its flaws: some ill-chosen examples of supposedly good writing practice, including a paragraph from Claire Bishop’s 2012 book, Artificial Hells, in which the academic manages to use the dated term ‘surf the web’ not once, but twice. There is a use of emphasis (bold, italics, colour) so liberal that every other sentence is presented as if it is the end-all of literary flare. Williams also has the bad habit of comparing totally disparate things – a memorable passage contrasts Dave Hickey discussing the 1970s: ‘limos, homos, bimbos, resort communities’, to the ‘pile-ups of Kunsthalles and Kunstvereins some art-writers try to pass off as a legitimate paragraph’. Still, her systematic analysis of the current state of art writing is a first and, when looking beyond her textual analysis, her examples can serve as a jumping-off point from which to review the field, its terms of engagement and what is at stake.

In the world Williams describes, the old-school critic is gone, replaced by a ‘jack of all trades’, but she does not dwell on the origin of this disappearance – the reality of writing about art, which is low pay, freelance hustle and a constant struggle to keep one’s ethics in check – or its consequences. While Williams acknowledges that writers are implicated in some way in the larger art economy, the conclusion she draws is that ‘today’s critics are not as powerful as they once were […] Occupying almost the bottom economic tier of the art-industry pyramid, critics are least affected by cycles of boom and bust. When art bubbles burst, art-writers often have more to write about and nothing special to worry about. As Boris Groys asserts, since nobody reads or invests in art-criticism anyway, its authors can feel liberated to be as frank as they please, writing with few or no strings attached.’ Does a position of power enslave a writer? Not necessarily. In fact, it could give the critic further traction and support his/her role as someone that should – and potentially could – keep the market in check. As for Groys’s assessment that no one reads criticism anymore, the conclusion that should be drawn from it is that what we urgently need right now is not more writing, but more critical writing.

No book could teach a writer to be interesting, opinionated, engaged or passionate. And that isn’t the objective of this one. Its goal is to take a discipline that Williams conceives of as highly unregulated – and professionalize it. In outlining exactly how an auction catalogue differs from a museum’s wall label and a magazine review, down to the vocabulary and tone each should accommodate, Williams gives insight to the inner workings of very different industries: academia, auction houses and mainstream and professional press. With an eye on the rise of numerous academic programmes in art writing, a book on the subject could be seen as a democratizing entity, but the difference between a book and a school is interaction. Even if one recoils at the idea of needing an MFA in art criticism in order to write for a magazine – another instance of an art world in which the terms of participation are a secondary degree, often accompanied by academic debt that few can financially justify – at least those programmes allow students a sense of community. Whether found in a graduate programme or not, it is the participation in discourse and interest in one’s contemporaries that makes someone a critic. Williams’s technique is married to the work of art – let the work lead you – which risks resulting in formulaic art writing that neglects the intellectual context from which the artwork emerges.

Art writing is not an industry in crisis – quite the opposite. Art publishing has developed into a realm complementary to the work, not one that merely describes it. The physical and conceptual expansion of what art can be has also produced a publishing landscape with a positive anything-goes ethos, which we should promote, rather than suffocate. Writing about art has become a space in which good writers can discuss anything, lofty or mundane, from politics to neckties, philosophical trends to internet memes. While Williams claims that art writing needs to be grounded in descriptions of the art – the ‘what’s there’ – I’d argue that this extended field of publishing is what makes for vibrant reading material, whether or not it ever mentions that this or that video installation has two screens and a total running time of 15 minutes. Art writing should be sharp and opinionated, but also sometimes flimsy and erratic. Art writing doesn’t need to be professionalized further – it needs to be granted room to experiment and expand. These more wayward forms of writing create an art world that is more perceptive, where what we read is equal in its intellectual ambition to the work we look at.