The Eleventh Busan Biennale is Refreshingly Local

Both regional and international artists probe the history and identity of the port city, offering a template for other biennials to stave away hyper-globalist perspectives

Both regional and international artists probe the history and identity of the port city, offering a template for other biennials to stave away hyper-globalist perspectives

From its beginnings as the self-organized Busan Youth Biennale in 1981 through its evolution into the government-led Sea Art Festival in 1987 to its launch as an international art event in 2002, the Busan Biennale has continually expanded its scope. By contrast, the tenth edition is refreshingly local. Opened to the public on the same day as Frieze Seoul, this year’s biennial in the smaller city of Busan offers an antidote to the frenzied atmosphere in the capital, taking a slower, more intimate approach to exhibition-making. Ultimately, the biennial acts as an intermediary between a specific place and its international neighbours without depending on the promise of globalism.

Aptly titled ‘We, on the Rising Wave’, given both Typhoon Hinnamnor’s landfall on opening weekend and South Korea’s rising status on the world stage, this year’s Busan Biennale, under the artistic direction of Haeju Kim, is a culmination of the trajectory begun by its last two editions, curated by Jacob Fabricius (2020) and Cristina Ricupero (2018). Those two biennials sought to capitalize on the underappreciated legacy of the city’s industrial past, using satellite venues – an empty bank building from the Japanese colonial period, redundant sites near the container port – beyond the Museum of Contemporary Art Busan.

This year’s biennial goes a step further, closely examining Busan’s history and identity as a port city, with the wide selection of artists who hail from the region making clear this local focus. In works such as Anotherframe 01 (2006), for instance, Lee In-Mi captures Busan’s changing urban landscape in a series of monochrome photos of high-rise residential complexes. Elsewhere, Kam Min Kyung’s large charcoal drawing, A Song of Dongsook (2022), in which the artist recalls her early years in Busan, is accompanied by a long excerpt from an eponymous novel on the disappearance of places in the wake of unilateral urban redevelopment projects. And Choi Ho Chul’s 2011 newspaper illustration of the thousands-strong march in support of Kim Jinsook – an activist who lived in a crane in one of Busan’s ports for more than six months to protest the laying off of a worker and aggressive police suppression – is reproduced as the large-scale digital pigment print on canvas, Yeongdo, Busan, 2011 (2011 / 2022).

However, it is not only participating artists from Busan who draw from the local context. Overseas artists have likewise created new works that respond to the immediate environment, suggesting that an effective discourse between local and global can evolve from a negotiation of existing artistic languages. Greeting visitors at the entrance to the Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, for instance, is Untitled: Bluechatcher (2022) – a concrete-dipped net taken from a Busan fishing boat – by British artist Phyllida Barlow, known for her largescale sculptures wrought from industrial materials. Mounira Al Solh collaborated with Hantya, a local feminist bookshop, to translate and distribute her magazine NOA (Not Only Arabic) (2008–ongoing), which cannot be publicly disseminated in her native Beirut.

Coinciding with the arrival of an international art fair on a scale that the country has never experienced before, this year’s Busan Biennale offers a template for how a large-scale exhibition can retain a focus on local history and identity while accounting for diverse perspectives. Installed in a now-defunct shipbuilding factory, Mire Lee’s Landscape with Many Holes: Skins of Yeongdo Sea (2022) perhaps best encapsulates this ethos. The 40-metre-per-second winds of Typhoon Hinnamnor damaged the work: the structure became minutely slanted, with bigger and looser holes throughout. But the sculpture will not be restored: rather, it has been reconfigured by local conditions to speak a new language.

‘Busan Biennale 2022’ is on view at various venues until 6 November

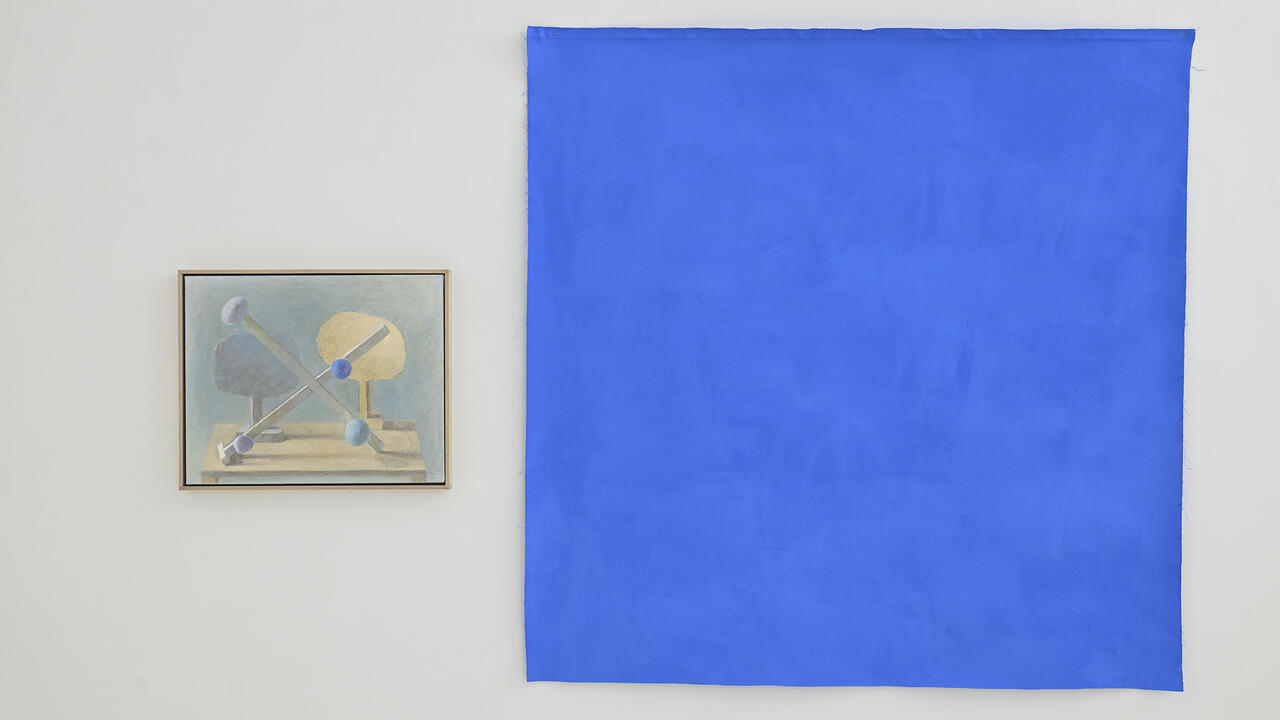

Main image: ‘Busan Biennale 2022’, installation view