Piecing together Cady Noland’s ‘THE CLIP-ON METHOD’

Accompanying her show at Galerie Buchholz in New York, the artist’s new book leaves readers to navigate her labyrinthine conceptual practice

Accompanying her show at Galerie Buchholz in New York, the artist’s new book leaves readers to navigate her labyrinthine conceptual practice

The summer fare at New York City galleries is usually a predictable pabulum of group shows – a miscellany of works from in-house rosters, more often than not a hodgepodge of disparate expressions rather than collective effort. Galerie Buchholz has broken the seasonal mould twice over, with a project defiantly monographic and ostensibly self-effacing at the same time. Cady Noland’s name appears on the spine of the two-volume tome accompanied by the show, THE CLIP-ON METHOD, which shares its name with the artist’s 1989 mixed-media installation: a raised metal bar affixed to the gallery floor, onto which are clipped an assortment of unrelated objects, from a shoehorn to a cowbell. Other than a double dedication to the artist’s mother and her teacher Stephen N. Butler (an African-American professor of sociology), these underproduced books evacuate personal authorship in place of various texts, documents and articles. Seemingly printed at a Kinko’s (if those still exist), the volumes contain everything from a 1978 essay from The American Sociological Review to a report on Boeing Airlines and Ethel Person’s essay ‘Manipulativeness in Entrepreneurs and Psychopaths’.

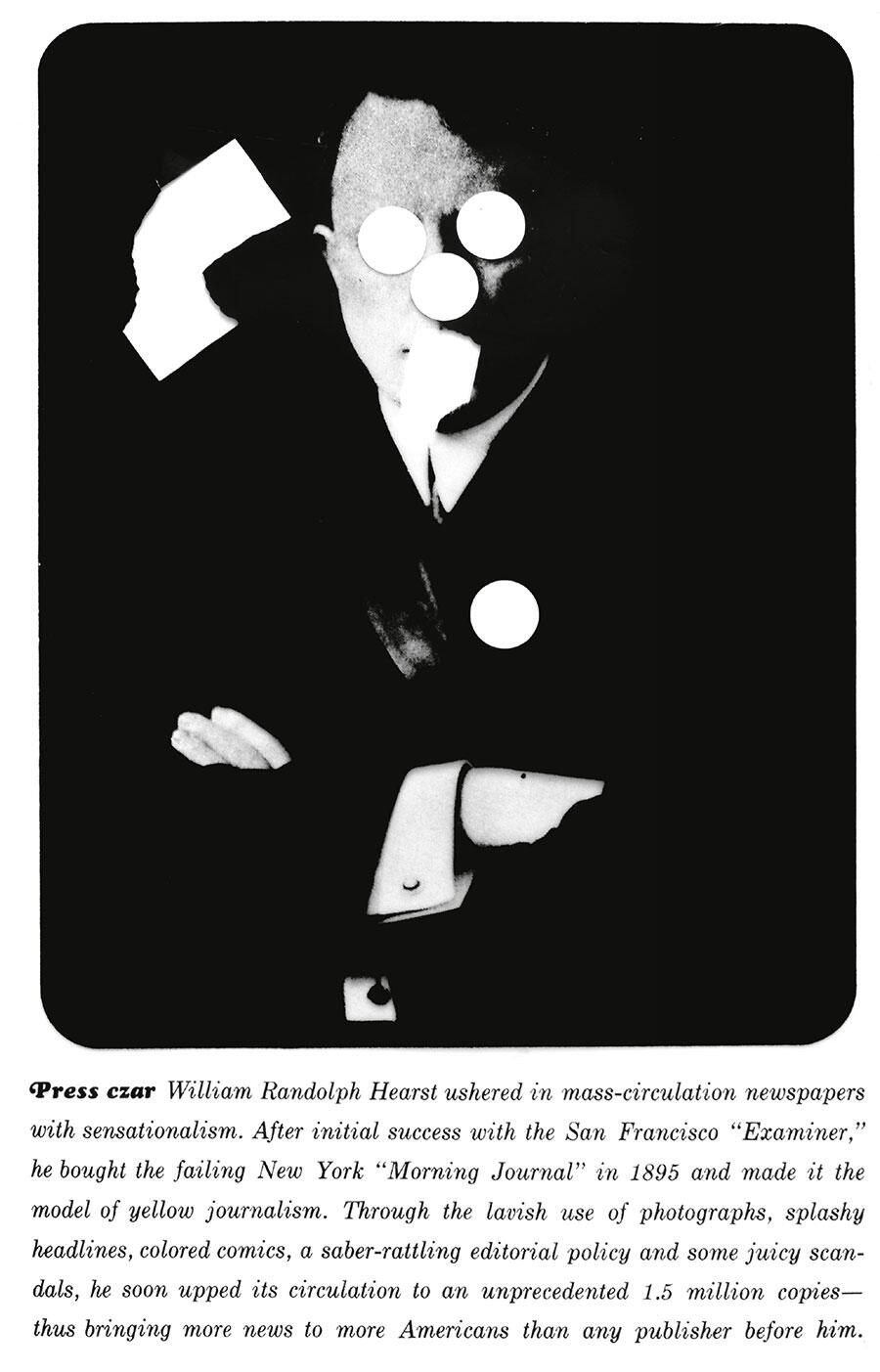

To be sure, Noland’s own work appears interspersed in photographic reproduction throughout the same pages, bearing the same visual and semantic weight as other texts. In one such work a crumpled American flag sits in a wire crate next to a police holster, handcuffs and steel pipes; another reveals a large, free-standing election poster for William Randolph Hearst; still another page bears installation shots of her larger-than-life aluminium cut-out of Lee Harvey Oswald. The simulacrum of his infamous assassination photograph reveals JFK’s alleged assassin riddled with stylized bullet holes, his mouth stuffed with an American flag and twisted in an eternal grimace. Anyone familiar with Noland’s work will recognize these as some of her best-known.

So, what are we dealing with here? Is the artist’s body of (artistic, conceptual) work meant to be read in aesthetic apposition to these miscellaneous texts? Or in dialogue with them? Or nourished upon them? The books leave us to navigate these questions on our own. One volume consists mostly of (unnamed, undated) reproductions of the artist’s assemblages and installations; the other packs its pages with a mix of artworks and photocopied articles. One such folio (also gracing its volume’s cover) reproduces a silkscreen by Noland of an annotated page from ‘Types of Police Patrol’, illustrated by a photograph of a (apparently white) mounted police officer. At what do these juxtapositions aim? Like the American flag next to handcuffs and steel pipes (in Noland’s Pipes in a Basket, 1989), they perhaps offer some insight into Noland’s conceptual practice. That practice doggedly separates objects and images as much as it brings them together. Chain-link fences, metal barriers and cages feature regularly, in apparent allusion to policies of exclusion and containment, proscription and suppression.

I say ‘policies’ because Noland’s work, like that of Alfredo Jaar and Hans Haacke, bears upon wider, often insidious practices by institutions both local and global, governmental and cultural. Though Noland famously retreated from the art world for a time, her works have gained a renewed poignancy in the (post-)Trump era; the sight of makeshift metal scaffolding with the US flag and stacks of Budweiser (in Untitled, 1989) appears to have anticipated with uncanny mordancy America’s carceral immigration policies on the southern border, for instance. The galvanized steel fence and plastic barricades installed against the blindingly white walls of Galerie Buchholz echo these previous works and occasion a reconsideration of the artist’s prescience. Like any institutional critique worth its proverbial salt, both Noland’s books and the body of work that they document are staked upon an almost clinical aridity and attendant irony. In the wry vein of Noland’s larger conceptual strategies, THE CLIP-ON METHOD and the show by the same name are, for all intents and purposes, interchangeable. In an art world still strained by COVID-19, that interchangeability is an auspicious one; what matters most are the intellectual constellations that it makes possible and portable.

Main Image: Cady Noland, ‘THE CLIP-ON METHOD’, 2021, exhibition view. Courtesy: the artist, Rhea Anastas and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin; photograph: Carter Seddon