California in a State of Creative Incubation

Marko Gluhaich profiles five figures leading the charge in education in Los Angeles and beyond, from Catherine Opie to Mercedes Dorame

Marko Gluhaich profiles five figures leading the charge in education in Los Angeles and beyond, from Catherine Opie to Mercedes Dorame

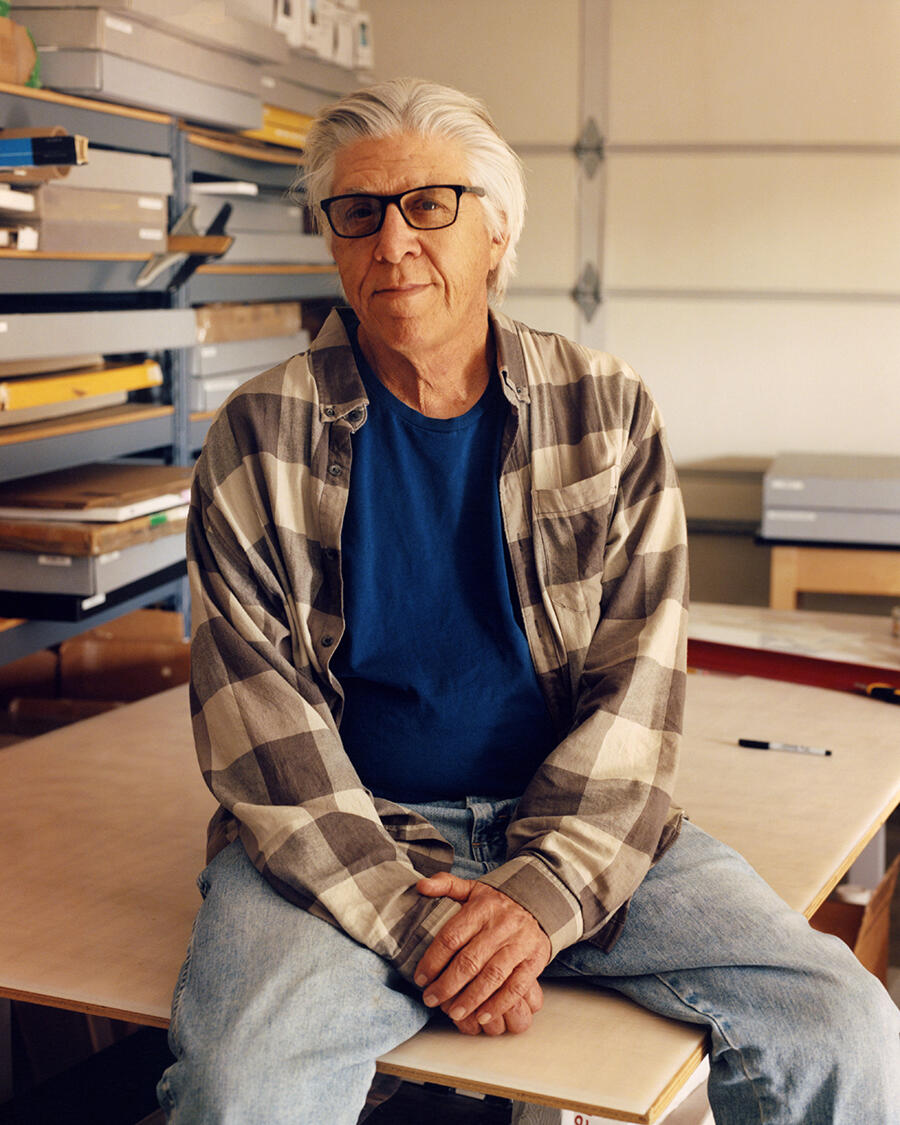

John Divola

Professor of Art, University of California, Riverside

John Divola has always tested the limits of photographic technology. His early black and white series “Vandalism” (1974 –75), experimented with how silver within the image would interact with the silver nitrate of the prints’ chemical composition; his spray-painted dots and patterns appear stellar on the walls of abandoned Los Angeles homes. “As Far as I Could Get” (1996–97) shows Divola running away from his camera, the shutter capturing the image after a ten-second self-timer. Recently, he’s been working with GigaPans, a technology that creates a panorama by stitching together several images that together total billions of pixels, though Divola uses this format in more intimate environments (say, a room of an abandoned building) than you might expect from a panorama.

Divola has become synonymous with the photography program at University of California, Riverside, where he has taught for the past 33 years. With its one-of-a-kind program, as well as being home to the California Museum of Photography which has one of the largest photographic collections on the West Coast, UC Riverside was a great fit for Divola — who, just a few years into his tenure, was appointed chair of the art department, a position he would hold for eight years. This turned out to be an auspicious move for the department since, by 2000, Divola’s initiative to launch a photography MFA had been realized. And, as the artist told me when we spoke in November 2021, the overlooked, newish UC Riverside had plenty of room for growth and hasn’t seen the humanities funding cuts afflicting the STEM-focused public university system in California.

Divola told me that he sees how his students’ relationship to the technology of photography has changed over the years — moves from analogue to digital, from horizontal to vertical orientation, from field to studio — although this hasn’t changed the format of his classes too much. He seeks out an unstructured space for creative incubation, propelling students using the momentum they bring to the program. He might offer them a simple framework — say, telling them to make an abstract photo — but this remains as undefined as possible, so the student has to make their own decision. Divola is there to help refine his students’ processes through Socratic questioning — a refinement that, he hopes, will maximize their potential.

Mercedes Dorame

Visiting Faculty, California Institute of the Arts and the University of California, Los Angeles

Mercedes Dorame’s practice bridges two former careers: student photojournalist and cultural consultant. The latter describes a position she held during and after pursuing her undergraduate degree, when she would travel across Los Angeles County to construction sites at burial grounds on the unceded land of the Gabrielino-Tongva — a native people to which Dorame belongs — and advise workers on what to do with the Indigenous artefacts they found there. As a student, Dorame learned how little documentation there is of the Gabrielino-Tongva, who remain unrecognized by the US federal government, and has since worked to bridge the gaps in the sparse history that has been recorded.

Dorame’s practice reinscribes Indigenous history onto land from which that history is actively being removed. In the series “Earth the Same as Heaven: ’Ooxor ’Eyaa Tokuupar” (2018), for example, the artist stages ceremonial interventions in the LA landscape — a fox skin surrounded by cinnamon, for instance — which she then photographs. The works activate their surroundings, reminding the viewer of a long-invisible Indigenous presence. Blending fact (the stolen land) and fiction (the invented ceremony), Dorame’s works echo her belief that “the imagined can be equally as powerful as fact”.

Dorame teaches at the California Institute of the Arts and the University of California, Los Angeles, where her position as an Indigenous faculty member comes to the fore in her pedagogy. She both instructs —bringing in texts and artworks from Indigenous artists and artists of colour, works that she knows deeply but that her students may not — and holds space for questioning. She sees this questioning as holding value both in the classroom and in the studio. A Dorame crit emphasizes looking, replicating the experience of someone viewing an artwork without the artist there to explain what the work “means.” This enables students to see not only whether their work is communicating in the way they want it to, but also how, when it deals with personal history — as with Dorame’s own practice — it isn’t always possible to relay that entire history to the viewer, since there will always be spaces of possibility. Dorame gives her students the ability to listen for those spaces and to let their curiosity fill them.

Lacey Lennon

Assistant Professor, California State University, Long Beach

It’s hard to tell that the subjects in Lacey Lennon’s photographs are often actors. Her recent images stage performers in situations from her own family history. Take The Smiling Pictures 1 (Judy and Her Girls) (2019): two younger women flank an older woman, who could be their mother. The girls — one confident, the other wistful — have the strained look of wanting to escape, while the woman in the centre, chest out, grips their waists. Despite bearing little resemblance to each other, they appear related, their expressions feeding off some unspoken connection pulsing between them. In the style of Black American neorealist cinema, Lennon’s photographs play with fact and fiction to uncover a wide range of Black subjectivities.

Lennon first considered the relationship between performance and photography while taking classes with Jenn Joy and Tavia Nyong’o at the Yale School of Art, where she did her MFA. In Joy’s class, for example, students paired movement-based exercises with a reading from Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons (2013). These assignments encouraged Lennon to reconsider the non-verbal histories contained in her body — histories derived from personal and familial experiences. It was then that she shifted from the documentary-style photography which had defined her earlier work to one that turned the camera on herself and her own memories.

This ethos translates into the way Lennon teaches. Originally at Yale Norfolk School of Art and now at California State University, Long Beach, where she’s an assistant professor, Lennon blends performance into her photography lessons, considering its relationship to truth-telling. In a class taught by Lennon, students will read a work like Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993), as an example of tangling fact and fiction, while also engaging in movement- and partner-based exercises. Many of these derive from Lennon’s own practice, whether it’s an inquiry into the meaning of “witnessing” or a long excursion across LA to mimic the activity of finding a filming location.

So much of Lennon’s classes are self-guided: the exercises, the interactions between students, the responses to reading. She wants to set her students on their own paths to understanding themselves and their relationship to photography, enabling them to gain the confidence to share their ideas and knowledge, and to understand the generosity this requires.

Catherine Opie

Chair of the UCLA Department of Art and Professor, University of California, Los Angeles

Catherine Opie has long concerned herself with ideas of community. Her work deconstructs mainstream conceptions of her subjects, whether by styling portraits of Californian queer communities after Dutch old-master paintings (“Being and Having,” 1991) or depicting high-school jocks as vulnerable teenagers (“High School Football,” 2012). In “Domestic” (1995–98), she captured lesbian families across the US within the context of their home lives, while she navigated her own relationship to family and motherhood. In these works, Opie uncovers what unites a community and tracks the individuals that comprise it.

Community-building also drives her work as a teacher and administrator. As a long-time professor in the photography department of the University of California, Los Angeles, Opie has built an artistic community for her students. In December 2021, she told me that she loves how welcoming LA’s arts community is and how supportive and non-hierarchical its members are. She seeks to use her platform within the university not to impose a particular path upon students but to help facilitate their momentum.

With rent and tuition costs rising, however, the question has shifted from how to integrate students into the LA arts community to how to make it affordable for them to stay. Since beginning as chair of the UCLA art department in 2021, Opie has kept this in mind and aims to ensure her students can live financially viable lives as artists beyond the program. Her plans to achieve this are unprecedented and ambitious but could set a standard for other art schools.

One of her initial focuses is to ensure that all graduates are debt-free by creating scholarships for students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. She also plans to set up weekend seminars detailing the various ways to support an artistic practice — whether through financial planning or applying for grants and residencies — something she sees as missing from art-school curricula. To facilitate career growth for her students, she plans to implement an internship program through which they will have access to various LA institutions and learn about a spectrum of art-world jobs, from commercial galleries to museums and non-profits.

Opie doesn’t want to see the old LA slip away. She’s doing a fantastic job of maintaining a friendly, supportive community where students are welcomed — whether into the classroom or the gallery — with open arms.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Associate Professor, University of California, San Diego

In the photography of Paul Mpagi Sepuya, the nude body, which is its frequent subject, isn’t the most intimate part of the composition; rather, it’s the glimpse we get into the photographer’s studio: bare intermingling limbs reflected in mirrors or jutting out of sheets; equipment strewn on the floor. In his self-portraits, smudged traces of bodies are visible on the surface of the mirror, around which hang torn-up pieces of drafting paper and other art-making detritus. All of this makes it seem like the studio isn’t ready for our presence; we’d be voyeurs if it weren’t for the artist’s careful compositions.

It’s LA, Sepuya told me in December 2021, that makes this work possible. Having left California for New York in 2000, aged 17, to attend New York University, the artist never thought he’d return to the West Coast. While he studied to be a pop fashion photographer in the style of David LaChapelle, Sepuya’s NYU professors — including Lorie Novak, Editha Mesina, Fred Ritchin and Deb Willis — provided him with the technical, material and historical foundation that underpins his work today. Alongside this, he learned how to fund and support artistic projects through arts initiatives like Creative Capital and the Joan Mitchell Foundation. After graduating, Sepuya pursued a series of residencies between 2009 and 2011 at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the Center for Photography at Woodstock and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Having failed to receive the mentorship and engagement he had hoped for, however, he returned to California in 2014 to pursue an MFA at UCLA, where he studied with Catherine Opie and James Welling. One thing LA had that New York couldn’t offer was space, affording Sepuya the expansiveness that, in turn, expanded his own vision for his work.

In addition to his LA-based studio practice, Sepuya serves as associate professor in visual arts at University of California, San Diego. His classes are structured around a regular critique format, and Sepuya encourages his students to ask themselves a series of questions: what is it about photography that they care about and why are they working with the camera? In doing so, he hopes students will surprise themselves. It’s clear from the success of Sepuya’s own practice that these questions serve as an excellent framework: you cannot imagine his work in any other medium; the camera is always just as present and important as the artist, his subjects and their environment.

This article first appeared in Frieze Week, February 2022 under the headline ‘Learning Curve’.