Petrit Halilaj Reads History in Classroom Desks

The artist’s show at kurimanzutto, New York grapples with a transgenerational experience of a conflict that’s often overlooked and largely unresolved

The artist’s show at kurimanzutto, New York grapples with a transgenerational experience of a conflict that’s often overlooked and largely unresolved

The Kosovo War is considered to have ended in June 1999 after the Kumanovo Agreement was signed by the International Security Force and the governments of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Republic of Serbia. Yet today, the region remains disputed; Kosovo is still not a member of the UN, many member countries don’t recognize its sovereignty and as recently as 2022 Serbia considered deploying 1000 troops to its southern neighbour. The notion that history can be easily grafted onto a timeline is complicated by Kosovar artist Petrit Halilaj’s exhibition ‘Abetare (Noisy Classroom)’ at kurimanzutto, New York, in which he conveys the complex, enduring realities of violence, displacement and trauma through local materials and voices.

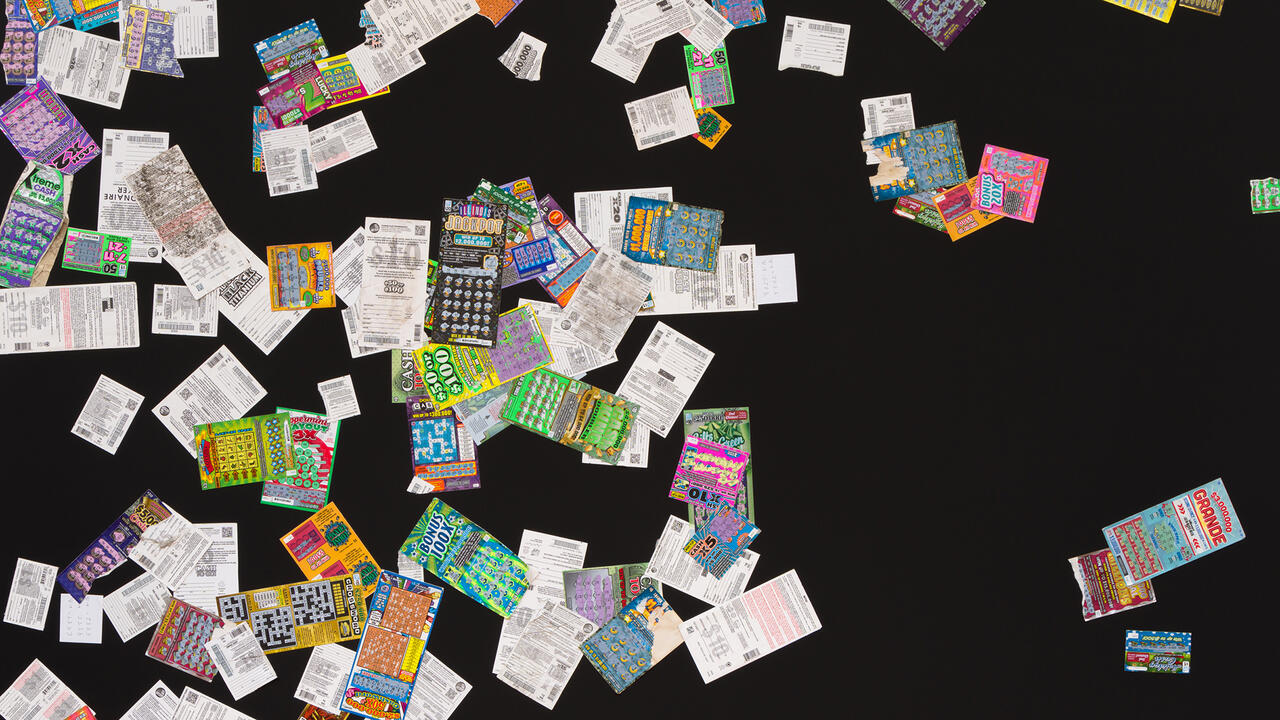

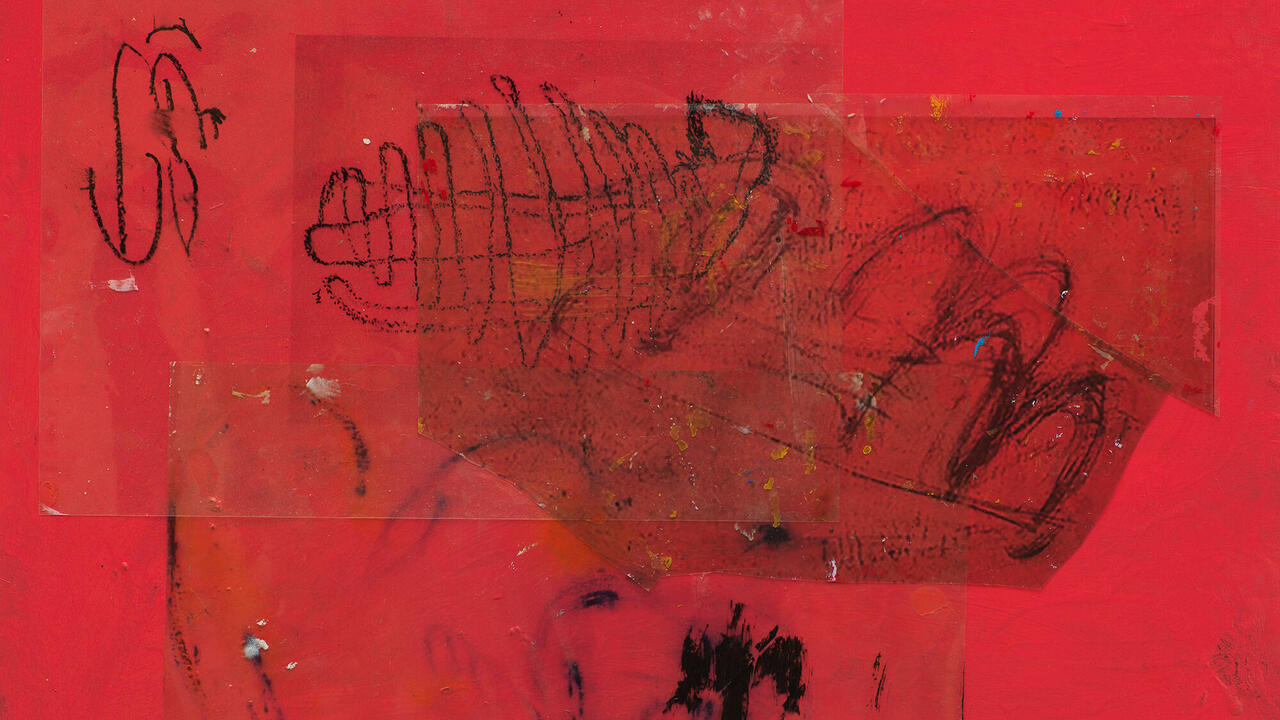

‘Abetare’ sees Halilaj continuing his eponymous series of classroom tables and large-scale bronze sculptures based on the apparently puerile etchings and drawings on their surfaces. The tables are tattered from years of use; in a 2024 interview with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, where related sculptures by the artist are on view, Halilaj speculated that they date back to the 1970s when Kosovo was part of a unified Yugoslavia. The scribbles and words may document a country in strife, of children at risk of almost-inevitable displacement – the fate of at least 90% of Kosovo-Albanians during the height of Serbian aggression. Such readings emerge from etched phrases like ‘lirie lendi’, which means ‘freedom of speech’, or a sketch of two machine guns beside the onomatopoeia ‘tik-tak’ – haunting representations of what Kosovar children were seeing and hearing.

Halilaj, however, complicates notions that these desks are tethered to a specific time frame of belligerent action (1998–99); names like ‘Cardi B’, for instance, betray their more recent history. When the artist first presented the series (2015–ongoing), the desks had been recovered from his primary school, which was being demolished some 13 years after surviving the war which almost entirely destroyed the artist’s home village of Runik. He has since gathered desks from across Kosovo and presented them as classroom-style installations like the one we see at kurimanzutto, but also in more surrealistic configurations, as when they appear to be crawling up walls.

In this iteration, tables mounted on the gallery’s pastel walls (Abetare Painting (Rabbit, Bird and Fuck You), and Abetare Painting (Chicken and Melting Heart), both 2024, for instance) evoke colour-field paintings – with Halilaj’s twisted bronze sculptures of cute animals and hearts emerging from their edges. Instead of reading the tabletop graffiti with a craned neck or in the form of Halilaj’s sculptural renderings, we meet them at eye level, which drew to my mind Leo Steinberg’s essay on Robert Rauschenberg, ‘The Flatbed Picture Plane’ (1968/72). That artist’s wall-works called attention to their former horizontality and status as a working surface, characterized by Steinberg as ‘the outward symbol of the mind as a running transformer of the external world, constantly ingesting incoming unprocessed data to be mapped in an overcharged field.’

What better description is there for the scribbles of a schoolchild who struggles to find words for the trauma they experience outside the classroom walls? ‘Abetare’ gets its name from an Albanian spelling book used by Halilaj as a student; its colourful xeroxed pages are wall-papered to the gallery’s entryway. It’s a subtle but radical gesture: in the manner of many oppressive regimes, Serbia banned the use of Albanian in Kosovar schools, stripping Kosovo-Albanians of the language they could use to describe the atrocities they witnessed. Through its ambiguous temporalities, Halilaj’s exhibition not only documents this violent legacy, but also powerfully underscores its ongoing character. These compelling works nod to a transgenerational experience of a conflict that’s often overlooked and largely unresolved.

Petrit Halilaj, ‘Abetare (Noisy Classroom)’ is on view at kurimanzutto, New York until 19 October

Main image: ‘Abetare (Noisy Classroom)’, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy: the artist and kurimanzutto, New York; photograph: Billie Clarken