Cecilia Vicuña’s Poetry Challenges ‘Authoritarian Monolingualism’

Alejandro Zambra on how reading Vicuña helped him lose his fear of writing

Alejandro Zambra on how reading Vicuña helped him lose his fear of writing

I was in the university cafeteria, stirring a sickly sweet Nescafé with a popsicle stick, when a classmate told me that an informal performance by Cecilia Vicuña was about to start in a second-floor classroom. At the time – this was in 1995, maybe 1996 – my limited idea of a performance had much to do with the atmosphere of a death-metal concert: people screaming and throwing things at the audience. I ran upstairs so as not to miss a second of that spectacle but, instead of the shouts I’d expected, the room was dominated by a warm, complicit silence: Vicuña merely gazed at us with a beautiful, crooked smile, as if in reality she were the audience, the whole audience, and the 15 or 20 of us watching were actually the ones putting on a show. Or, rather: as if she already knew us and wanted to get to know us again; as if she had seen us as children and now, with loving curiosity, was noting the passage of time in our posturing as brand-new twentysomethings.

Suddenly, as if on impulse, Vicuña picked up a copy of that day’s El Mercurio newspaper and started to sing the supposedly objective journalistic prose to an uncertain, improvised melody. At times she whispered; at others, she raised her voice, moved by a fit of enthusiasm, as if she were getting to the good part of a tango or a bolero. I remember it took me a while to realize that the reading was not the introduction, but the performance itself. Afterwards, I wanted to approach Vicuña in the hallway, but I wouldn’t have known what to say, except to thank her.

‘That stuff’s not vanguard anymore,’ someone said afterwards, in the courtyard, with the air of a connoisseur. To us, the word ‘vanguard’ designated something almost sacred, and maybe also contradictorily classic. Many of us were at university studying literature precisely because we had been lucky enough as teenagers to read Vicente Huidobro’s Altazor (1931) and much of what we had come to understand as great literature included emblematic works by the Latin American vanguard. ‘I don’t know if it’s vanguard or not,’ replied another classmate, after a long silence, ‘but when I grow up, I want to be as wise as that crazy old lady.’ His words felt necessary, so luminous and unforgettable.

Also unforgettable, for me, was that simple yet unexpected performance. From that morning on, I started reading Vicuña daily. By which I mean in the daily paper: every time I came across a copy of El Mercurio, I found myself imitating the fluctuations of her voice, at times with fits of laughter, at others with consternation. But a year went by, maybe two, before I started reading her poetry – thanks to my teacher, Soledad Bianchi, who was responsible for my first encounters with so many important writers’ work, including Pedro Lemebel’s nonfiction and Elena Garro’s magnificent novel, Memories of the Future (1963).

Ezra Pound’s famous definition of literature as ‘news that stays news’ is particularly germane when thinking of Vicuña’s work, which taught some of us to read the newspaper: her poetry has, for decades, kept us abreast of the news of today, tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. Amid the climate crisis and indigenous peoples’ ongoing, arduous attempts to recover cultures and plundered lands, amid our continued frustration at the knowledge that we are still living in an age of war and in-communication, Vicuña’s work is impressive yet painful, and its lessons inexhaustible.

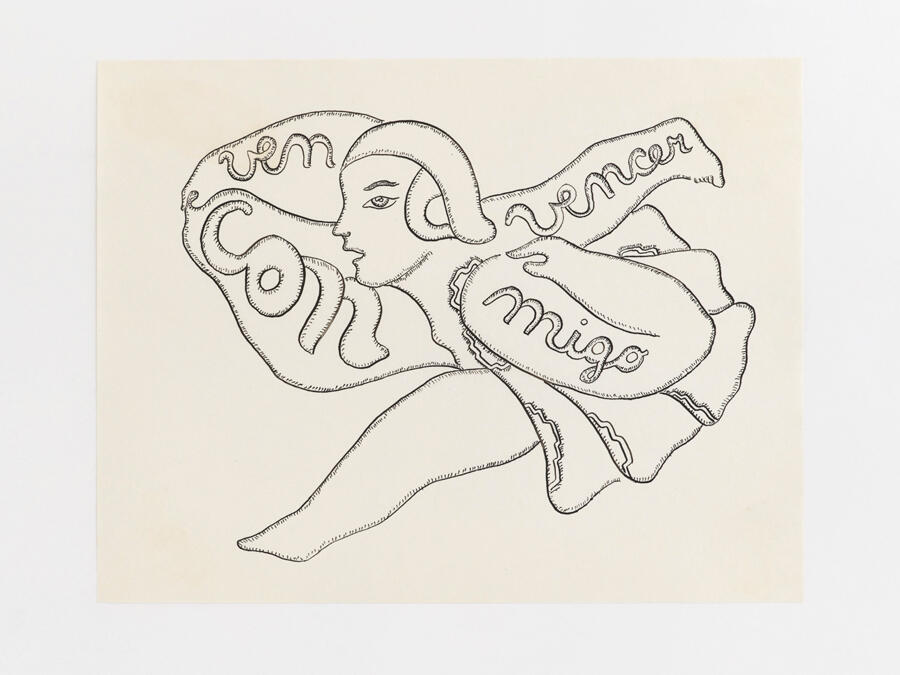

‘I want to be a Native / hiding in the hills / who never comes down the valleys / because everything hurts,’ writes or sings Vicuña in ‘Beloved Friend’. She lives everywhere and doesn’t renounce anything, not her own pain or that of others. Her work can be read as a defence of cross-cultural mestizaje, or as an open and joyful challenge to the authoritarian monolingualism that wants to erase all, or as an urgent call to a true reconciliation with nature, or in a thousand other ways. None of them, in any case, could encapsulate a body of work that has been able to exist without limiting itself to a few certainties or in a single mode of expression. ‘I don’t believe in the crystalline,’ she writes in her 1967 poem ‘El silencio es algo en ruinas’. ‘Purity is not my thing / My pores scratch away to end my endless virginity.’

In the same way that, after listening to Violeta Parra’s songs, many Chileans picked up the guitar and lost – for ten minutes or four hours or for the rest of our lives – our fear of singing, Vicuña likewise helped so many of us lose our fear of writing, and let us know that writing poems is not the only way to make poetry. I don’t think it’s too late to thank her for that.

– Alejandro Zambra, translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell

‘Cecilia Vicuña’s Poetry Challenges ‘Authoritarian Monolingualism’’ first appeared in frieze issue 229 as part of the festschrift ‘I Am Green: An homage to Cecilia Vicuña’, alongside ‘The Sound and Feel of Cecilia Vicuña’s Art’, ‘‘A Form of Praying’: The Performances of Cecilia Vicuña’ and her poem ‘Silence is in ruins’.

‘Hyundai Commission: Cecilia Vicuña’ will be on view in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern, London from 11 October 2022 to 16 April 2023.

Main image: Cecilia Vicuña, mtChondrial Eve (Mother of Threads), 2008, performance, MoMA PS1, New York. Courtesy: the artist and New York / Hong Kong / Seoul / London