Chris Burden

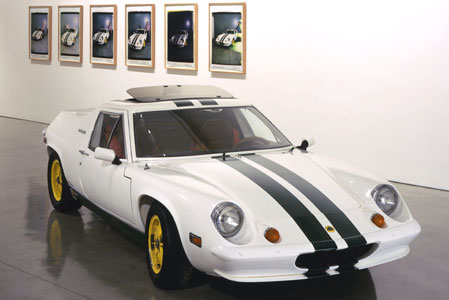

Ready-mades are the lightning rods of the art world. If it looks like your child could make it, we still sometimes wonder about emperors and their new high-end threads. Sign a urinal, and we’re still talking about it 90 years later. In this case Gagosian invited Chris Burden to put on a summer show, and it looked as though the idea was thought up during a telephone call: a request, a pause, the muffled sound of a hand over the receiver, then a quick ‘yeah, we can do that’. What was delivered to the gallery were simply two vehicles owned by the artist himself: Lotus (2006), a 1973 Lotus Europa (along with six photographs of the sports car), and Bulldozer (2007), a 1954 International Harvester T-6 Crawler (with four photographs). The title of this two-car garage of a show, ‘Yin Yang’, was the only clue pointing to any meaning; but it was all anyone needed, for while at first glance the show looked brazenly empty, it was in fact quite full.

Colin Chapman, who founded the Lotus sports car company in Britain, always privileged lightness over simply packing more horsepower into a chassis (the American ideal), and this Lotus Europa, with its competition stripes and racing harnesses, seemed poised to zip around a track. Contrast this with the heavy-duty tractor, which spoke of farms, heartland, individual labour and a time before thoroughly industrialized agribusiness. Both cars also operate as surrogates for the artist himself: the quick-manoeuvring Europa a portrait of the artist as a young man, the stolid T-6 (coincidentally the same age as Burden) a portrait of the artist today – still chugging along stoically, in love with overkill, taking care of business. This incongruous pair, parked in the gallery’s Beverly Hills location (where ‘you are what you drive’ has more meaning and cachet than elsewhere), speaks volumes.

These are objects that have not only been used but also cared for and loved. Driving them straight into the white cube reinvests them with a charm and dignity they deserve – more like exhibiting a loyal show pony and ox than a blender and refrigerator. From the freshly waxed body of the Lotus (with its registration all up to date) to the tiny sprig of green growing out of the radiator of the tractor, we begin to discern the personality that many of us invest in our cars (where others might see themselves in their pets). With that awareness these things become more than just vehicles, more than art even. They are some of the things that make our days bearable (or unbearable once they break down).

The photographs look amateurish; exposures are wildly all over the place, sometimes out of focus, rarely spot-on. They showed Burden standing next to his trusty steeds, with a Cheshire cat grin, or blankly peering over his glasses. Others feature studio assistants, with Burden nowhere to be seen. This slightly awkward scenography is partly due to the fact that they were made with a large-format Polaroid camera (so big and exclusive that it requires its own technician to accompany it). Since each photo is unique, it is hard to get things just right, hence the range of exposures (and hence, presumably, the inclusion of assistants, probably substituting for Burden as he aimed to get light levels correct, like stand-ins on a Hollywood set). Another layer of meaning to this onion presents itself in the fact that the photographs, the one medium we usually associate with reproduction, are one-of-a-kinds. By contrast, the vehicles, although rarely seen on the roads, become the multiple.

This installation contained the sorts of quiet revelations mulled over for decades, slowly finding fruition. If we look at the many dualities that sprout from Burden’s simple intervention, they pop up everywhere: old/new, Continental/domestic, heavy/light, play/work, original/multiple, cute/ugly, East/West, representation/object, deadpan/stirring, flawed/elegant. It is about loving objects, as well as letting go of them (in this case for ten times their worth, which softens the blow), which gives us one more unexpected couplet: bargain basement/top shelf. Kudos to the collector who, however many thousands of bucks lighter in the wallet, feels the weight of wisdom that Taoist philosopher Lao Tse spoke of nearly a thousand years ago: ‘Be content with what you have; rejoice in the way things are. When you realize there is nothing lacking, the whole world belongs to you.’