Club Rules

A recent performance about masculinity and sport revealed cultural exclusion within the art world

A recent performance about masculinity and sport revealed cultural exclusion within the art world

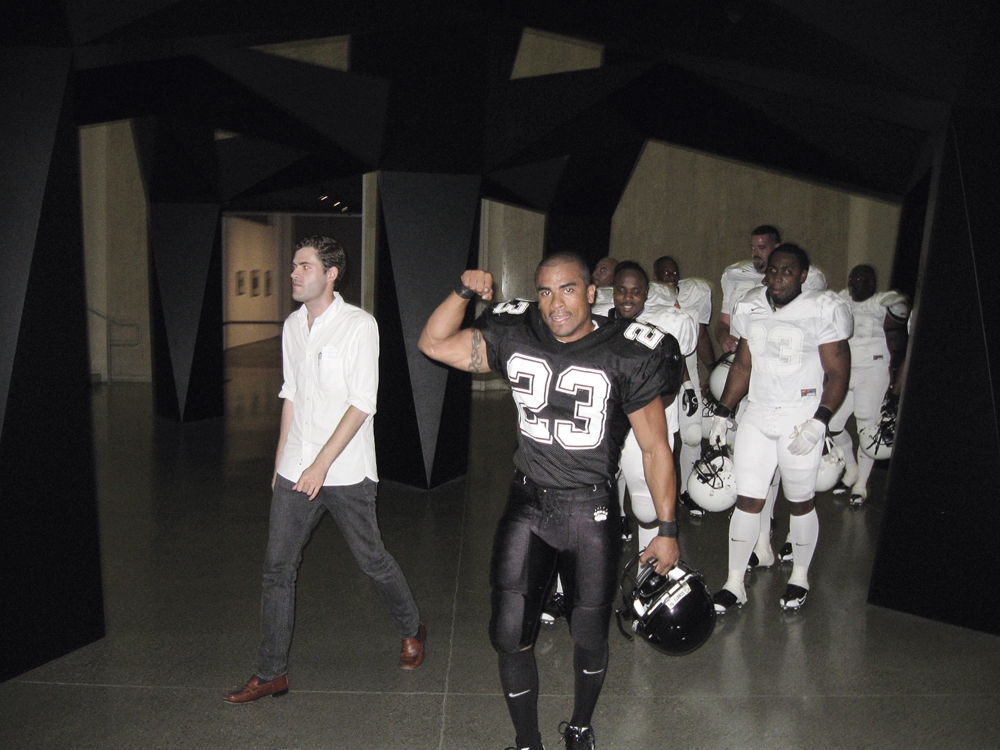

Thunderous, unruly, and larger than life, on the evening of 7 October 2008, ten semi-pro football players in mismatched jerseys yanked down over partially exposed pads, their features concealed under battered helmets, tentatively made their way through the bowels of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, past publications and the registrar’s office, towards a manicured square of grass adjacent to Renzo Piano’s new Broad Museum of Contemporary Art at LACMA. Led by the relatively diminutive Queens-based performance artist, Shaun El C. Leonardo, the players looked like oversized interlopers visiting a Lilliputian world. Those corridors, usually host to circumspect art handlers, elegantly appointed curators, and scurrying museum educators, appeared ready to burst at the seams.

That night was a rehearsal for a live performance that would precede the reception for an exhibition I organized for LACMA called ‘Hard Targets: Masculinity and Sport’, scheduled to open the following day. True to time-honoured curatorial precepts, I had commissioned Leonardo to conceive a performance that would speak to the concerns of my exhibition, namely the ways in which images of male athletes and the stage of sports shape our collective understanding of masculinity, and, most vitally, the efforts of artists to scramble this equation. Leonardo described the performance to me in an email as follows:

‘Bull in the Ring is the term used to describe a specific training routine banned from American football on the high school and collegiate levels. In its original form, the team would form a revolving circle, and one player would be chosen to enter the centre of the ring (the matador). One by one, players would be selected by their coach at random (the bull) to charge the player at the centre, possibly catching him off guard to deliver a blow – the object being to have the centre player develop alertness by “keeping [his] head on a swivel” and defending himself from all oncoming offenders.’

Chief among my interests was a social phenomenon branded ‘homosociality’ by the literary theorist, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, who used the term to describe the rituals of male bonding and expressions of guarded affection that structure heterosexual (and homophobic) all-male social networks. Closely guarded and fiercely insular, football teams render homosocial relations strikingly literal. In the locker room unusually intimate exchanges are commonplace, while on the practice field, intra-squad violence is offset by an unflagging loyalty to the team-concept. Brutality, then, is code for heterosexuality and thus an alibi for otherwise outlawed intimacy. Under these circumstances, transgression – sexual or otherwise – is effectively impossible.

With these seductive dialectics in hand, I felt confident writing a pre-facto interpretation of Leonardo’s performance for the ‘Hard Targets’ brochure: ‘The artist’s participation in the drill, and his accompanying sculpture of the same title, gave brutal metaphoric form to the sacraments of inclusion and exclusion that structure the fraternal dynamics of sports teams from the inside but remain largely hidden from public view, even as sporting events often take place before thousands of people.’ The backstage mechanics and spectacle of the performance served as ample justification for this analysis. There was no shortage of pre-performance bravado, locker-room sanctioned physical contact, and jocular accusations of homosexuality, and what took place on the field during the rehearsal and the performance certainly highlighted the drive shared by football players countrywide to establish the quality of their manhood through public displays of toughness.

But jarring as the ferocity of the performance was, there exist concepts and language to frame, contain, even tame the most extreme of spectacles. The impulse to complicate, invert, or just throw into relief a familiar social identity through performance is as native to the art world as broken bones and concussions are to football, and my text for the exhibition brochure was as guilty as any other of clinging to those conservative precepts for analytical clarity. With these critical precedents in mind, interpretation comes easily, and is summed up in a well-known Barbara Kruger text-based work from 1981: ‘You construct intricate rituals which allow you to touch the skin of other men.’ However, there was a far more unsettling dimension to Bull in the Ring than art critical discourse has the language or willingness to describe.

After a dramatic entrance and a theatrical stretching routine, replete with the artist as drill instructor barking orders to his cadre, the ten football players – clad head to foot in white – and the artist – dressed in black – assumed their positions for the performance. Poised in the centre of the circle, Leonardo readied his body for the hits that came fast and furious from the ten players circling him. Raw and unmediated, each helmet to helmet, pad to pad collision registered as a deep, dull thud that seemed to leave each player reverberating. Meanwhile, most of the crowd had assembled behind an adjacent wall, wincing and recoiling with each hit. While a group of sports fans would, undoubtedly, have crowded the action, eager to absorb and reflect the performance in all its ferocity, this group observed with something like rapt repulsion from a safe distance.

The art world prides itself on an all-encompassing ethics of inclusion of what we blithely call ‘difference.’ But there are limits to these ethics, and they are to be found where the ideologies of the art world meet popular cultural expressions that have never held a strong place in our social or discursive orbits. There are very few of these thresholds left, to be sure, but the collision of art and sport as discrete ideological fields stands as one emphatic example.

What was different about Bull in the Ring had nothing to do with violence per se, since, like identity, violence has a long history in performance art. What was different, however, were the types of bodies involved, and the relationship of those specific bodies to the typical demographics of an invitation-only art-world event in a major metropolitan centre. Oversized, tattooed, perhaps threatening, and thickly – not cosmetically – muscled, these were not artist’s bodies or the hairless, lithe forms found in gyms around LA, but the damaged bodies of men belonging to another social stratum entirely.

Hispanic, African American and White, some college educated, others not, all playing full-contact football for little or no financial gain in informal leagues around Los Angeles, the ten players in Leonardo’s performance represented not only the antithesis of the conventional museum patron, but in cultural profile – working class, sport-loving, beer-drinking, heterosexual males – were embodiments of everything the art world is not and, perhaps unwittingly, demeans and excludes under blanket terms like ‘normative’. Yet in the context of that evening, passive neglect became manifest as a form of aloof prejudice that caused the performers – normally the centre of attention – to sit alone in groups at the reception, as glaringly discrete from the museum ‘natives’ as they had been as performers. As artist’s collaborators in a choreographed event the identity of the football players could at least be understood as critically provocative, but beyond the performance, that same identity apparently held no critical interest and laid bare a stark social schism.

Bearing in mind the cultural profile of the average museum patron – upper-middle class and highly educated – it was hard not to see this division as symptomatic of deeper class lines in the United States drawn according to socio-economic status, level of education and race. Far from the dominant group that night, Leonardo’s collaborators occupied the margins of the art world’s centre, and the fact that such a dynamic could exist within a cultural field that prides itself on its embrace of difference and inclusion is to the detriment of the hermetic world we occupy.

Performance is, fundamentally, an art of process, and as such its effect is subject to any number of contingencies, most of which arise from the specific context in which the work unfolds. For better or worse, LACMA and its audience remade Bull in the Ring. What was scripted to be a performance about masculinity and sport emerged instead as one that addressed more insidious cultural rifts; prejudices the art world often chooses not to articulate. That the ten football players who participated in the piece would test Leonardo’s body was to be expected, but that their presence in the museum would also amplify cultural biases generally ignored within our community was an unexpected, even unpleasant, dose of impromptu institutional critique.