Collaborative Relationships: How Living and Loving Informed New Ways of Making Art

The forthcoming exhibition ‘Modern Couples’ frames the shared lives of modernism’s artistic pairings – from Claudel and Rodin, to Maar and Picasso

The forthcoming exhibition ‘Modern Couples’ frames the shared lives of modernism’s artistic pairings – from Claudel and Rodin, to Maar and Picasso

I have a deep loathing of the word ‘muse.’ Not the ancient mythical inhabitants of Parnassus – Calliope, Melpomene, Terpsichore and their ilk – but in the modern sense of the term. ‘Muse’ suggests a figure of radiant passivity: a creature of mute allure. It is a romanticised label for the marginal, objectified role that women have played (often, played naked) in western art. The Muse is the submissive counterpart to the Lone Male Genius. However prettified and aspirational, it is ultimately part of a tradition that prioritises men’s creativity over women’s – the one memorably described by comedian Hannah Gadsby as ‘the history of men painting women as if they’re flesh vases for their dick flowers’.

The western story of modern art, in its received version, is awash with muses. The exhibition ‘Picasso 1932 – Love Fame Tragedy’ at Tate Modern earlier this year found Picasso, the artist-as-genius, in a lather of creative excitement over Marie-Thérèse Walter. Twenty-eight years his junior, Walter is pictured asleep or patiently seated, and generally nude.

As Jane Alison, co-curator of ‘Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde’ writes in that exhibition’s catalogue: while the surrealists prized women and celebrated ‘feminine’ traits such as hysteria, they ‘needed, above all else, their female companions to be sexually available and extremely beautiful’. By way of counterbalance, ‘Modern Couples’ argues for an understanding of modernism based on collaborative relationships: new ways of living and loving that informed new ways of making art. Alison quotes Ben Nicholson saying of Barbara Hepworth: ‘Barbara and I are the SAME’. He and she could ‘live, think & work & move & stay still together as if we were one person.’ Similarly, she suggests the influence that designer and businesswoman Emilie Flöge – pioneer of reform dress, and avid collector of precious, patterned textiles – had on Gustav Klimt.

‘Modern Couples’ is part of a gradual re-evaluation of the role women played in art’s stories. The Hepworth Wakefield’s recent Lee Miller exhibition sought to liberate her from her role as muse to Man Ray, suggesting a collaborative role in both studio and dark room, and establishing her talent as a photographer. Likewise, the paintings of Leonora Carrington are now exhibited beyond the sphere of influence of her lover Max Ernst.

How the crowds now thronging the V&A’s ‘Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up’ might laugh at the 1933 newspaper article announcing that the Wife of the Master Mural Painter Diego Rivera Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art. Yet the tendency to view work by female artists in terms of their relationships with prominent male counterparts has not been laid to rest. Profiles of female artists still seldom resist pointing out that X once worked for Damien Hirst, nor that Y one had a relationship with Lucian Freud.

No wonder, then, that the question of mutual influence between artist-couples remains fraught. Artists are still so widely presented as solo operators, that to suggest one is working under the influence of another sounds dangerously belittling – particularly so in the case of women artists. For decades it was considered demeaning to cite, for example, the important role Alfred Stieglitz played in Georgia O’Keeffe’s life and art, as if to do so was to question her greatness. The painter Rose Wylie has preferred her work to be shown outside of the context of her long marriage to the artist and writer Roy Oxlade.

If we seek to lay the passive, compliant figure of the muse to rest in favour of a more active, collaborative, creative understanding of the role women have played historically, we need to accept that influence passes in both directions. Or indeed in many directions: to accept that an artist does not operate in a creative vacuum, but draws on the ideas, acts and language of friends, family and lovers alike.

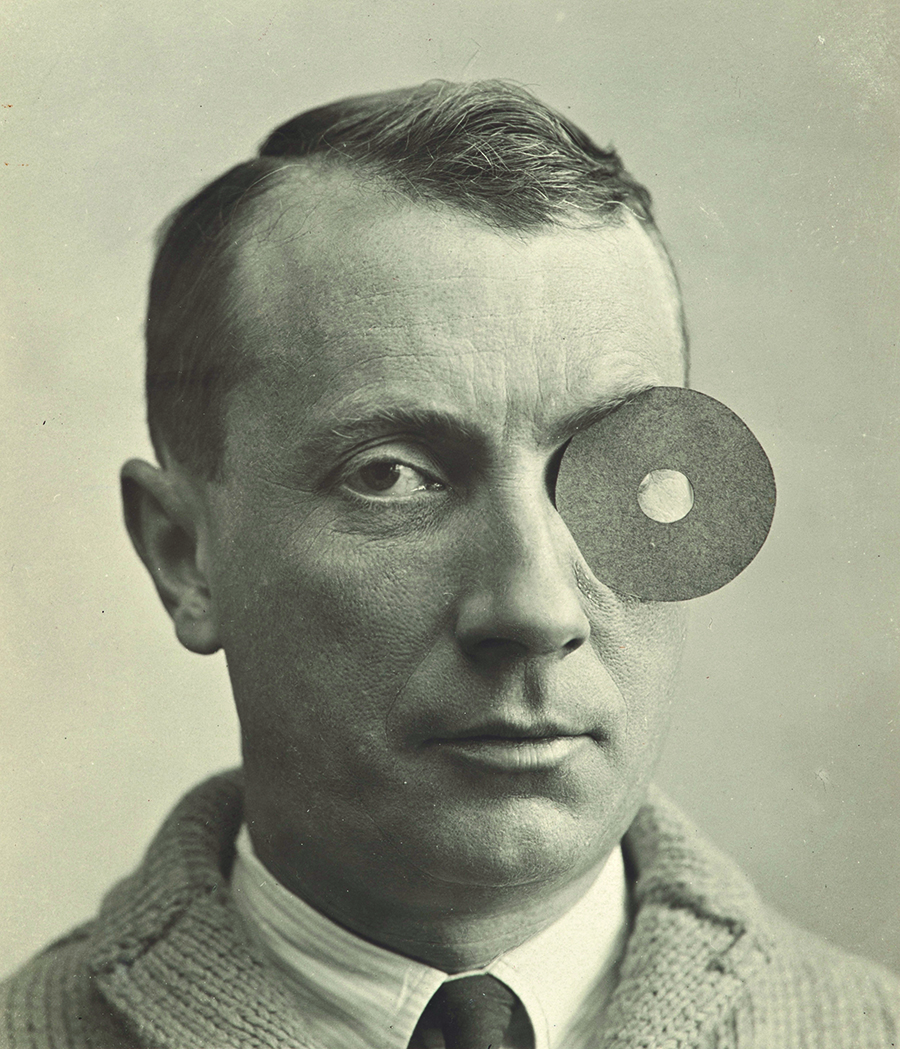

It can be a struggle: even artists whose work is explicitly collaborative are commonly re-packaged. Thus we see the photographic masquerades of Claude Cahun exhibited without mention of Marcel Moore, the genital dreamscapes of Grace Pailthorpe without suggestion that Reuben Mednikoff may have held the brush. Does presenting artists as a neat, lone package make them easier to market? And if so, is that because it erases the presence of ‘troublesome’ relationships? Is this erasure a coy act?

‘Modern Couples’ is as unflinching in its treatment of the troubling – the doll of Alma Mahler that Oscar Kokoshka had made after their split, Marcel Duchamp’s fetishisation of the erotic plaster casts he made of sculptor Maria Martin’s intimate parts – but it is also celebratory. At its heart is Virginia Woolf’s subversive and celebratory 1928 Orlando, inspired by her affair with Vita Sackville West. Here, too, are Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Laionov, Benedetta and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti: living, working and experimenting à deux in place of the muse-genius relationship. Hand-holding, it turns out, is permitted in the avant-garde.

‘Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde’ runs at the Barbican, London from 10 October 2018—27 January 2019. Published in Frieze Week, London 2018, with the title ‘Seeing Double’.

Main image: Tamara De Lempicka, Les Deux Amies (The Two Friends), 1923. Courtesy: Association des Amis du Petit Palais, Geneva