Critic’s Guide: Berlin

The best shows opening as part Berlin Art Week

The best shows opening as part Berlin Art Week

Berlin Art Week is a citywide initiative funded by the city’s Senate Chancellery for Economics and the Senate Chancellery for Cultural Affairs. Since 2008 it has revolved around abc (Art Berlin Contemporary), which started as a hybrid exhibition format, halfway between curated show and art fair. Yet, as abc’s prominence has declined over the years, other events and institutions have come to the fore and the moniker has lost its precision; Berlin Art Week now spans the two to three weeks of the city’s artistic rentrée.

Natascha Sadr Haghighian, ‘onco-mickey-catch’

Neuer Berliner Kunstverein

15 September – 4 November

Exhibited upstairs, in the showroom, ‘onco-mickey-catch’, a project by Natascha Sadr Haghighian, treats the screen as a biopolitical tool: both the object of attention and the object capable of capturing attentive behaviour.1 The starting point is deceptively simple: the somewhat paradoxical notion of online face-to-face communication.

With video-conferencing you typically look at your conversation’s partner screen image (or your own), instead of staring at the camera. As a result your eyes rarely meet. CatchEye, an add-on for Skype, Hangouts and Messenger, is an application designed to force your eye not to wonder: the ‘Eye Contact’ reorientates your gaze towards the camera, ‘“enhancing” your “chat experience.”’ The app is installed here onto two monitors, which, in turn, protrude from the dorsal region of a furry mouse-like shape. The abnormal form is slightly reminiscent of the Vacanti mouse – the rodent Charles Vacanti used to grow ear-shaped cartilage, which became an internet sensation in the ’90s – which Sadr Haghighian ties to two other famous mice: the OncoMouse, genetically modified to become susceptible to cancerous tumours (a registered trademark, the OncoMouse was the first fully patented animal), and Mickey Mouse, often a shorthand for the military-entertainment complex. But Mickey, much like the scopophilic culture he belongs to, is a relic of the past: our wholly interfaced infrastructures do not address users as desirous subjects but rather as units of attention to be tapped into.2 By juxtaposing technomorphs and optical technologies, Sadr Haghighian points to a fully autonomous model of vision, no longer tied to emotion, representation or cognition.

1 Jonathan Crary, Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999)

2 Orit Halpern, The Smart Mandate, in Nervous Systems-Quantified Life and the Social Question (Spector Books, 2015)

Halil Altındere, Space Refugee

Neuer Berliner Kunstverein

15 September – 6 November

Downstairs, NBK presents Turkish artist Halil Altındere’s ‘Space Refugee’, an exhibition revolving around the history of the Allepo-born Syrian cosmonaut Muhammed Ahmed Faris. In 1985, Faris took part in the joint Syrian-Russian space programme, travelling to the space station Mir. In the wake of the Syrian uprising, Faris defected from the regime and fled to Turkey, where he now lives as a refugee. Exalting Faris’ personal story, Altindere short circuits the image of the refugee (and of the Syrian populus in general) as uneducated, backward and poor, but Space Refugee has greater ambitions than to simply comment of the image of the Middle East. Faced with a growing humanitarian crisis the so-called first world responded with racism, de-humanizing its victims. Where to go when no country on Earth wants you? The answer, Faris sustains, is space.

Space (more concretely, Mars) belongs to no one, therefore belongs to all: the new utopian frontier for a truly equal mankind. ‘Space Refugee’ stages the logistics of Faris’s fantasy with scientific precision: underground colonies, supplied by horticultural stations, the costs of life-supporting systems (to transport one litre of water to Mars costs half a million US dollars), resource extraction machinery, 3-D printers. However visionary in its outline, ‘Space Refugee’ basks in nostalgia, tapping into Socialist Realism, the iconic aesthetics of NASA’s golden age and the familiar wonder of the full dome display. In Altındere’s hands, the future looks like the past, and space travel is not so much a place but an idea: an utopian dream of parity and participation, downright dissimilar from the biotech reality Sadr Haghighian outlines.

Nathalie Du Pasquier, ‘Meteorites & Constructions II’

Exile

8 September – 8 October

Exile is showing a series of recent paintings (Meteorites & Constructions II, 2013-16) by Nathalie Du Pasquier, who was a founding member of the Memphis Group, the Italian designer collective known for infusing irony and cultural commentary into industrial design. Du Pasquier, whose former paintings were reminiscent of early 20th century movements such as the Neue Sachlichkeit, signals with this new series a return to the playfulness and the anarchic instability Memphis was known for, but also a reversal of the traditional work process: whilst design objects start their life as two-dimensional blueprints, Meteorites & Constructions develop from three-dimensional assemblages.

Anna Ostoya

Silberkuppe

5 September to 29 October

Exhibiting at Silberkuppe, Anna Ostoya, also mines the Bauhaus aesthetics (clean lines, block colours, swift turnover) but disrupts it with incongruous elements: mud-like papier-maché, a photograph of the atomic bombing aftermath in Nagasaki, an unfolded American Spirit cigarette pack. The title ‘Alte Sachlichkeit’ addresses the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, whose somber realism forebode the coming Second World War. In ‘Alte Sachlichkeit’ all genres (realism, formalism, abstraction) seem to point to the remoteness of the modernist past, whose architecture, as T. J. Clark notes, is now only readable under a rubric of fantasy.

Jos de Gruyter and Harald Thys, ‘Pantelleria’

Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi

1 September – 5 November

This feeling of despondency is echoed by the halting and toneless voices of speech software in The Ape from Bloemfontein (2014) the central piece of Jos de Gruyter and Harald Thys’ show ‘Pantelleria’ at Isabella Bortolozzi. Surrounded by immaculately white steel panels holding measuring instruments (thermometers, barometers, compasses) the video, spoken in Afrikaans, recounts the story of ‘Jaap the chicken’ who ‘was also a monkey’ and ‘had a computer, that was actually a lawnmower, on which he watched TV.’ The narrative, animated by unstable forms and their constant transmutations, contrasts the deadening pace of the image sequence and the lethargy of the narrator’s voice, creating a dissociative effect between the sensory experience of sight and sound and the mental images they engender.

Sean Landers, ‘Small Brass Raffle Drum’

Capitain Petzel

16 September – 29 October

Never one to shy away from hallucinatory imagery, Sean Landers grounds his exhibition at Capitain Petzel ‘Small Brass Raffle Drum’ in a similarly jarring premise: each painting in the exhibition was based on seven randomly selected elements, which the artist picked from his own custom-built raffle drum. The figure of the lone sea-wolf recurs in Captain Homer (Seven Pipes for Seven Seas) (2016) as a stand-in for Landers himself, unsteadily navigating his phantasmal streams of consciousness.

Jutta Koether

Galerie Buchholz

16 September – 22 October

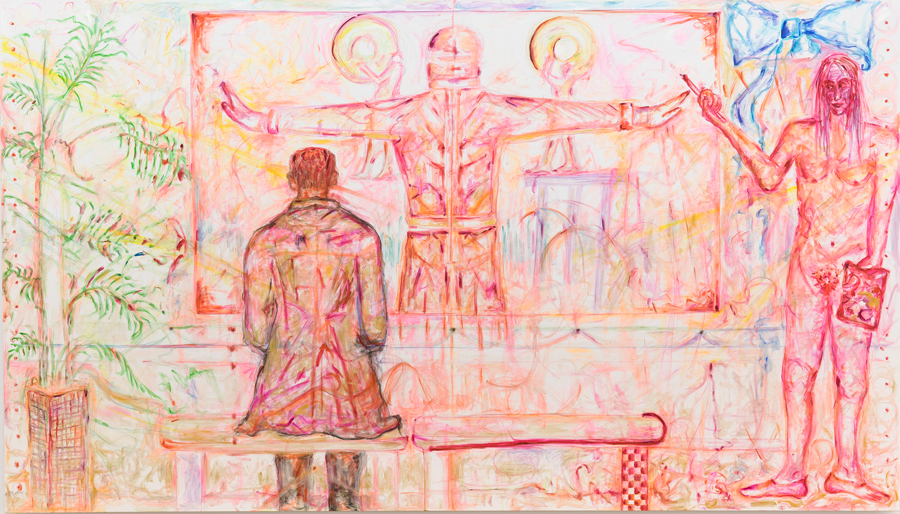

Whereas Landers paintings often offer themselves as a script to be deciphered, Jutta Koether courts the indeterminacy of visual meaning. ‘Zodiac Nudes’, exhibited at Galerie Buchholz, addresses painting as a gendered concept, typically personified as a female who enthrals the, most often male, painter. This libidinal economy, as the press release by Isabelle Graw points out, poses a difficulty for female painters. Koether’s answer is to appropriate the figures and formulas of her male colleagues in order to create fleshly and vulnerable images, which refuse to fall into showmanship and fetishization. Koether’s apples are never held upright, rather they are turned towards the viewer, like a breast – when shown in pairs they resemble the cut-off breasts of St Agatha – or an eye, encoding several contexts into their round form.

Eran Schaerf, ‘Stairs, Dogs & Underdogs’

Zwinger Galerie

16 September – 12 November

Last but not least, Eran Schaerf’s Stairs, ‘Dogs & Underdogs’, presented at Zwinger Galerie, interweaves several non-linear narratives, anchored by recurring images whose meaning is contingent to the plot for which they are recruited: there is Valie Export walking Peter Weibel on a dog leash (Mappe der Hundigkeit, 1968) and an attorney on all fours, re-enacting a dog attack in a Californian court. There is a couple eaves dropping on their upstairs neighbours’ violent fight, there again is the attorney on all fours, re-enacting how the wife is being beaten, there are dog-walkers in Mexico City forcing tranquilizers down their dogs throats, there is a black and white image of the Staatsbibliothek in Unter den Linden, juxtaposed to a video shot on the same room. The library staircase stands in for the staircase separating the two couples but also for the verticality of social hierarchies and their hidden gender dimensions, much as the handrail stands in for a leash and the pluripresent dogs become a proxy for master-slave asymmetries and a cipher for the struggle of the underclass.

Main image: Anna Ostoya, A Kiss, 2016, oil on canvas, 61 x 76 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Silberkuppe, Berlin; photograph: Timo Ohler