Critic’s Guide: Geneva

Ahead of Artgenève this week, a round-up of the best shows in the Swiss city

Ahead of Artgenève this week, a round-up of the best shows in the Swiss city

‘Nightfall: Gothic Imagination Since Frankenstein’

Musée Rath, Musée d’art et d’histoire

2 December 2016 – 19 March 2017

In 1816, Mary Shelley and her husband Percy travelled to Geneva to visit Lord Byron, then in exile in the countryside near Lake Geneva. The same year, volcano Tambora erupted in Indonesia, the biggest volcanic eruption ever recorded. It caused what was later described as ‘The Year Without a Summer’ in the Northern Hemisphere resulting in the worst famine of the 19th century. The bad weather and dark atmosphere would inspire Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein, published two years later. ‘Nightfall: Gothic Imagination Since Frankenstein’ is an extensive survey of Gothic motivations and themes in art over the years, with works from the 16th century until today. Sarah Lucas’ neon coffin and Sterling Ruby’s fabric sculptures happily neighbour early Francisco de Goya engravings and watercolours by John Ruskin. Surpassing the typical Medieval aesthetics and horror-story iconography, the exhibition brings a new reading of the Gothic, while tracing its controversial history.

Biennale de l'Image en Mouvement 2016

Various venues

10 November 2016 – 29 January 2017

Currently hosting its 15th edition and one of the oldest of its kind in Europe, this biennial has contributed to the democratization of video art since its inception in 1985. Curated by Andrea Bellini, Cecilia Alemani, Caroline Bourgeois and Elvira Dyangani, and spread across various venues in the art district of Quartier des Bain (primarily hosted in the Batiment d’Art Contemporain and l’Usine), 27 newly-commissioned works bear a strong focus on young filmmakers. Names such as Wu Tsang, Pauline Boudry & Renate Lorenz and Tracey Rose headline but the inclusion of lesser-known, non-Western and politically-engaged artists – such as Boris Mitić, Alessio di Zio, Bertille Bak, Hicham Berrada for example – is noteworthy and welcome. Catching its last days, make sure to see Exquisite Corpse (2016), a three-channel video by Kerry Tribe, which portrays the Los Angeles river, from its source in the San Fernando Valley to its mouth at the Pacific Ocean. Carefully following its geographical course (through the poor suburbs of Maywood to the lavish waterfront in Long Beach), the film is a poetic allegory of the varied populations living along its banks.

‘DOMESTIC - Like a Preraphaelite Brotherhood’

Truth & Consequences

27 January – 18 March 2017

Through a selection of small-scale works, mostly produced with organic material and using craft as their main technology, ‘DOMESTIC’ suggests the existence of an alternative to a certain idea of modernity heralded by ‘gigantism and the machine’. With a fresh take on 19th century artists groups such as the French post-Impressionist Nabis and the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood by curators Charlotte Cosson and Emmanuelle Luciani, the works on display – all by living artists – share a similar utopian faith that yearns for a less fragmented, more spiritual world through a re-evaluation of beauty with a capital B. Interestingly enough, what seems like a simplistic reaction to the polished and digital aesthetics of the critically defunct post-internet art might actually be its most logical development.

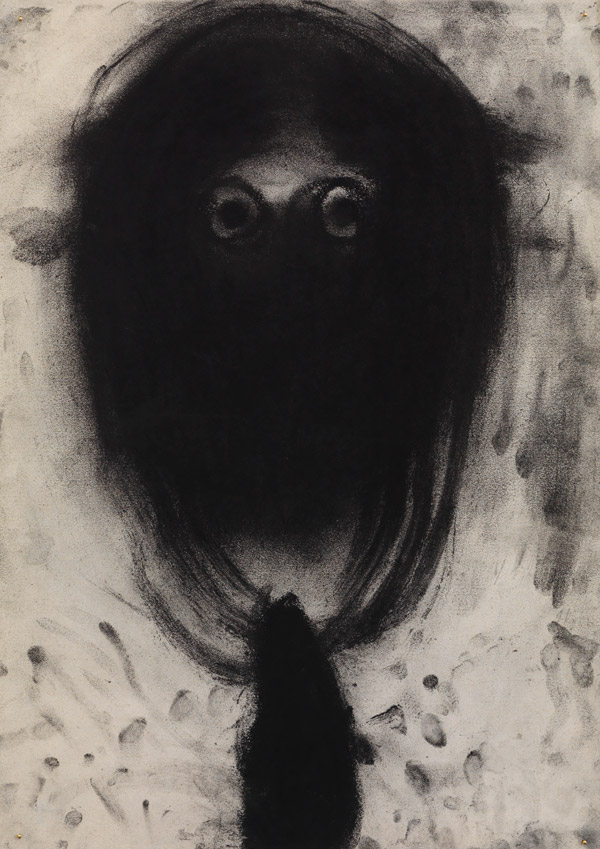

Miriam Cahn, ‘Works on Paper 1977 – 1985’

Blondeau & Cie

19 – 28 January 2017

Born in 1949, Miriam Cahn is often considered a standard bearer of Swiss feminist art. Working across performance, film, writing, drawing and painting, she puts the body at the centre of her practice – the body as both her main motif and also primary tool when generating drawings. Up until the 1990s, Cahn drew on the floor, crawling on large-scale sheets of paper during highly focused cycles that often lasted less than a few hours. In their brutal simplicity, the drawings on display appear as the leftovers from exercices of pure expression. Working with black chalk on paper, she recently emphasized in an interview that black signals colour through its absence, a simplification that, according to her, symbolizes strength. ‘Works on Paper 1977 – 1985’ shows, among others, series of distorted mask-like faces that introduce the more abstract side of Cahn’s early work.

Wade Guyton

MAMCO

12 October 2016 – 29 January 2017

Despite being digital prints of photographs, Wade Guyton considers his large-scale printed canvas as paintings. In what might be a tongue-in-cheek reading of Walter Benjamin’s concept of the loss of aura through the mechanical reproduction of art, Guyton enlarges and prints the same smartphone snapshot multiple times, provoking the machine to inevitably fail: the presence of dripping and glitches signals a data or ink overload, guaranteeing its auratic uniqueness. Among a generation of commercially successful male painters prioritizing large-scale and process-based works, Guyton manages to propose a rather eye pleasing and coherent corpus of 30 works shown on MAMCO’s freshly-designed first floor. But beyond its obvious monumental appeal, the exhibition conveys some essential aspects of contemporary painting in its attempt to question reproduction and authenticity.

Axelle Stiefel, ‘Das Herz’

Forde

21 January – 28 January 2017

‘Das Herz’ (the heart, in German), is the title of Axelle Stiefel’s first monographic exhibition. It’s drawn from Georg Trackl’s eponymous poem, which the artist recites in an enigmatic film that’s available on Forde’s website and immediately on view upon entering the exhibition space. An open-water landscape unravels from the back of a speed boat, it’s filtered in deep blood red, rhythmed by the monotonous voice of the artist and a mesmerizing soundtrack by UK music producer Patchfinder. Red, it seems, is the exhibition’s leitmotiv, included in each artwork, from the boat sails, neatly folded on the floor, to the printed hand towels and the artist’s personal archive of fashion shows, where only garments presenting a red line are pinned on the wall. In a constant, sometimes conflicting superposition of references (a trademark in Stiefel’s work), the colour red becomes the reassuring thread that guides the viewer into the artist’s cumulative process.

Jan Vorisek, ‘Total Fragmented Darkness’

Hard Hat

20 January – 13 March 2017

Possibly the smallest gallery in Geneva, Hard Hat is also one of the city’s most notorious. Founded in 2004 by John Armleder, Lionel Bovier, Christophe Chérix, Balthazar Lovay and Fabrice Stroun, it’s currently run by curator Denis Pernet. Since its inception it has uncovered an astonishing number of successful artists. For his inaugural solo exhibition in Geneva, Zurich-based artist and musician Jan Vorisek proposes a new site-specific installation consisting of objects found at flea markets, bought in shops or recycled from previous exhibitions. Like samples, they are reassembled and modified according to the artist’s mood and research interests. Selected for their material, sonic or visual qualities, the elements are later carefully arranged, connecting the artist’s previous installations while subtly announcing what’s to come.

Main image: Massimo D'Anolfi and Martina Parenti, Infinita Fabbrica del Duomo, 2015, film still; included in Biennale de l'Image en Mouvement 2016. Courtesy: Montmorency Film