Critic’s Guide: Los Angeles

A round-up of the city’s best current shows, to coincide with this year's Art Los Angeles Contemporary, which opens today

A round-up of the city’s best current shows, to coincide with this year's Art Los Angeles Contemporary, which opens today

‘Breaking News: Turning the Lens on Mass Media’

The Getty

20 December – 30 April

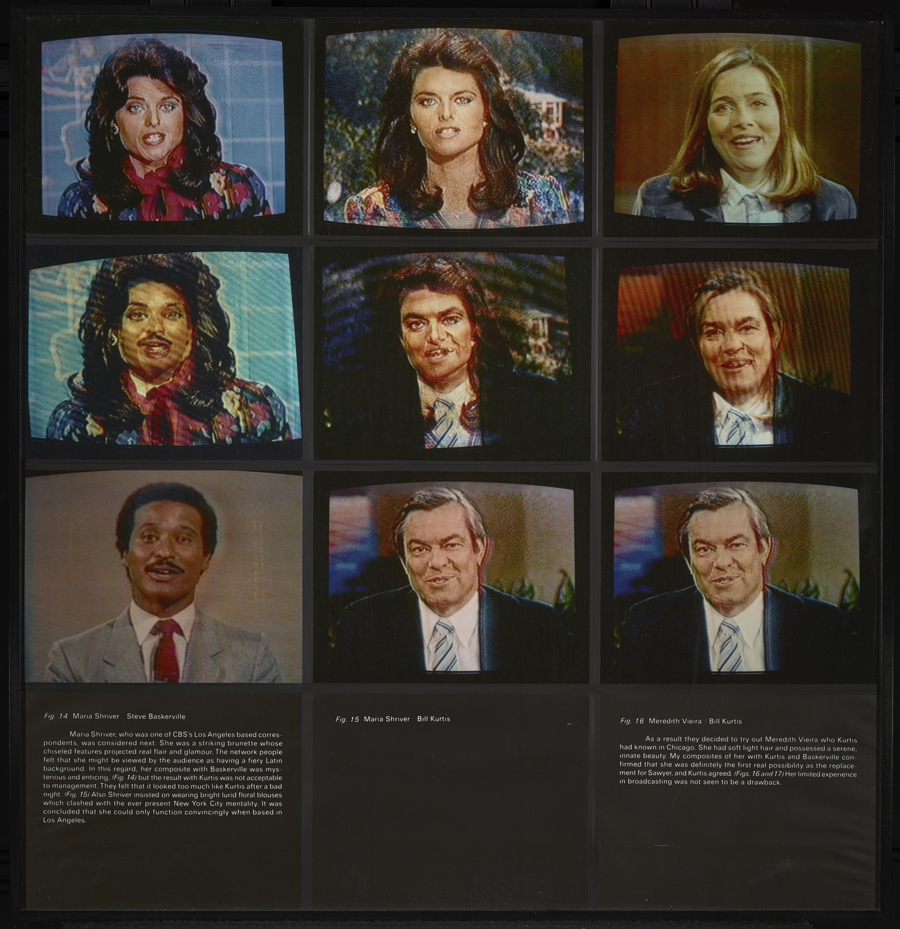

How many ways can you take a photograph of a televised news broadcast? How many ways can you reframing and image from the newspaper? According to ‘Breaking News: Turning the Lens on Mass Media’, a survey of news images as source material and subject for artists working in photo and video, the answer is a lot. We see, for example, the ways in which similar strategies have been utilized to a variety of effects across different contexts and political positions. Donald Blumberg’s grids of photos of TV screens address the anxieties and ideological fractures of the Vietnam era, while Masao Mochizuki’s grids of photos of TV screens, composed from the mid-1970s, address the logic of the televisual experience. (Robert Heinecken just had a thing for blonde newscasters.)

The news that is imagined, dissected and critiqued throughout the show is predominantly lifted from television and print, and one wonders how it could have been brought up to date. Even the 21st-century works included, Catherine Opie’s Polaroids of TV screens, for example, which circle around the invasion of Iraq, or Ron Jude’s appropriated pictures from an old small town newspaper, have an archaizing, nostalgic quality. But that aside, the show is thorough, as one would expect from the Getty, and one of its strengths is the pairing of lesser-known artists, like Mr. Blumberg himself, alongside the more familiar faces.

Linda Stark

Jenny’s

14 January – 25 February

The titular ‘Painted Ladies’ of Linda Stark’s show at Jenny’s are an odd bunch: cartoonish renderings of the female reproductive system, complete with fallopian tubes arms and frantic little hands. Ovaries are eyes. Vaginas become snouts or tentacles. The two oils on display, both older works created via a long and laborious process of layering, possess mesmerizing textures and near-sculpted surfaces. The first, the meticulously rendered Fixed Wave (2011) has a rather Pop sensibility, with a surface you might mistake for moulded plastic. The second, Coat of Arms (1991), curdling at the edges, could be taken for a devotional object from some folk religion. Those two evocations – Pop and the tradition of visionary or mystic art – underlie the talismanic repetitions that move as well through Stark’s more recent, and often deceptively delicate, works on paper.

Stark’s paintings and drawings are hilarious and mischievous, mythic while grounded in biological reality, but they are also timely, to say the least. I saw the show one day before Donald Trump’s inauguration, two days before joining some 750,000 others at the Women’s March on LA, and three days before our new President signed an executive order barring foreign aid from going to any NGO that provides abortions or even discusses them as a family planning option.

Theaster Gates

Regen Projects

14 January – 25 February

There is a tension built into Theaster Gates’s show at Regen Projects, one that he presents up-front – makes central to the experience of being there. The exhibition’s title comes from W.E.B. Du Bois’s classic, The Soul of Black Folks (1903): ‘To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships.’ The line haunts many of the very beautiful objects and paintings that constitute the bulk of the show – ceramics, sculptures in bronze and wood, elegant geometric abstractions. Gates explains Du Bois’s ‘poor race’ as having ‘a particular kind of poverty, one that is not just about a lack of economic capital but one that is deprived of the basic elements from which one can make a living.’ And here we are, in the heart of a blue chip gallery.

The question being asked here is not only of how much of the past remains present, but also of how we objectify and transmogrify that past for our own purposes. We see it when Gates frames old wooden gym flooring and mounts it on the wall, just as we see it in Black Harmonics, Like Space on a Page, and West Side Story (all 2017), the highpoints of the show, which comprise a vast collection of Jet magazines, library-bound in dozens of thick volumes, presented on three steel shelves. Launched in 1951, Jet was a popular weekly African-American digest, covering everything from entertainment and politics to wedding announcements and beauty tips. Collected together, these volumes amount to a rich archive of black cultural history. Well, they would, but here their content is inaccessible. Printed in gold letters along the spines is Gates’s poetry.

George Nelson Preston

Henry Taylor’s

14 January – 14 February

Poet, painter, art historian and Ghanaian chief George Nelson Preston has lived some interesting lives. An active member of the Beat circle in the 1950s, he founded the Artist’s Studio in Greenwich Village, which would later host readings by major and minor New York poets and novelists. Later, he had a hand in fostering the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s, and following that became a scholar of African art history. The five paintings and collages that comprise his show in the artist Henry Taylor’s living room each come out of a different chapter of this life. The earliest is a ghostly self-portrait from 1959, the most recent an abstract landscape of torn paper with acrylic, graphite and masking tape, made last year after an ayahuasca ceremony in Brazil. Supplementing Preston’s paintings are a mask and bronze relief from the Niger Delta (each dating back to the early 19th century), borrowed from the collection of friend and African art collector Jeremiah Cole. The show is spare, loose, and comes out of a long-pursued vision of the history and present of the Black Atlantic.

Laura Schawelka

Garden

9 December 2016 – 30 January

Garden occupies a spare room in a back apartment in an old terracotta building, and is the latest of a recent proliferation of project spaces housed in tool sheds and apartment galleries throughout Los Angeles (full disclosure: I run one in my backyard…). Is this phenomenon just a down-market response to a recent spate of new museums and a sharp influx of galleries from New York and Europe? Is it the Uberization of exhibition-making? Whatever the explanation, Laura Schawelka has used the space well. Covering one of the walls is wallpaper bearing a large image of Schawelka’s own hand resting in green goop. In fact, hands (and goop) prove to be major motifs: There are photos of golden hand-shaped reliquaries from the Guelph Treasure, and close-up images of Muscle Milk protein shake on black glass. It’s the hand as image, the hand as object and the mythic hand of the artist, all in one. Muscle Milk reappears again in an accompanying video, being poured over a car seat. The green slop is there, too, only we can’t see it as it’s green screen coloured, and it’s been keyed out. In its absence, there appears an image of a headless mannequin being hugged by a large smiling doll. It’s a nice moment.

Main image: Martha Rosler, First Lady (Pat Nixon) (detail), from the series 'House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home', c.1967–72. Courtesy: the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York