The Top Exhibitions to See During Tokyo Gendai

From Theaster Gates’s moving exploration of ‘Afro-Mingei’ to Futo Akiyoshi’s creative collaboration with critics and curators

From Theaster Gates’s moving exploration of ‘Afro-Mingei’ to Futo Akiyoshi’s creative collaboration with critics and curators

Kazuko Miyamoto | Take Ninagawa | 1 June – 10 August

Kazuko Miyamoto, a Japanese-born artist who has spent most of her life in New York, has been a critically important contributor not only to minimalism but also to process-based sculpture and conceptual performance. Too often overlooked, the octogenarian was not honoured with an institutional survey exhibition until 2022, at the Japan Society in New York. This delightful show at Take Ninagawa features drawings from the mid-1970s and string spatial constructions from the 1970s and ’80s. The majority of works here are made of string tied to nails, forming three-dimensional geometric patterns that transform based on the viewer’s perspective. Seen from afar, they appear hard-edged. Up close, these formally complex, hand-tied installations reveal themselves to feature lines of various densities and even degrees of shading. These are creations that demand to be seen in person.

Theaster Gates | Mori Art Museum | 24 April – 1 September

Theaster Gates’s first solo exhibition in Japan is a tightly composed and moving experience. It proposes the concept of ‘Afro-Mingei’, which draws parallels between African diaspora culture in the US, especially the Black is Beautiful movement that emerged in the 1960s, and the concept of Mingei, developed in Japan in the mid-1920s to champion utilitarian objects made by anonymous artisans. Gates, whose formative years as an artist were spent studying ceramics in Tokoname, sees both as cultures of resistance. The show opens with a shrine-like installation featuring Gates’s own works alongside those of others he respects. Paired with the incense-based Black Buddhist Scent Practices (2024), the sustained hum emanating from A Heavenly Chord (2022) – comprising a Hammond B3 organ and seven Leslie speakers – invites meditative contemplation. Gates’s Afro-Mingei vision culminates in the final room, where visitors can experience joyful emotional release amid disco tracks and Houseberg (2018/2024), an iceberg-shaped mirror-ball ode to house music.

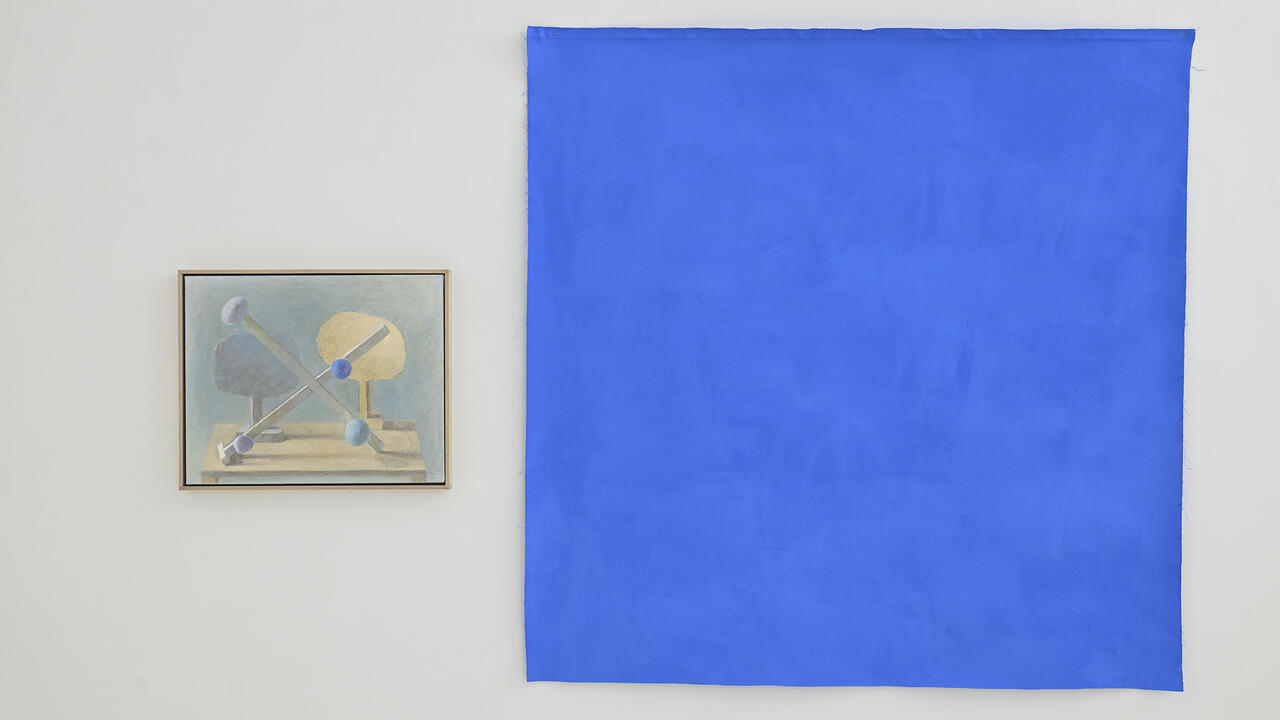

Futo Akiyoshi | TARO NASU | 22 June – 27 July

For ‘Godchildren’, Futo Akiyoshi produced 29 nearly monochromatic paintings of equal size. In each one a flatly-painted ground in a different colour is topped with a constellation of six tiny hemispherical dollops of varying hues. These smart paintings offer considerable visual interest with great economy. Futo distributed the pieces among 29 critics and curators, inviting them to name the works – like godparents to the artist’s offspring – and write an accompanying text to be exhibited with the paintings. These texts fit a handful of categories: the anecdotal, the impressionistic, the art historical, the phenomenological and the projective (one exception is independent curator Hikotaro Kanehira’s graceful submission of a colour photograph). Most of the responses feel defensive and humourless, as if their authors feared that their slip might show. Little attempt is made to frame the work beyond the context of art. Consequently, this exhibition of coolly composed paintings provocatively shows what happens when there’s nothing at stake in writing.

Katsuro Yoshida | Yumiko Chiba Associates | 8 June – 10 August

Katsuro Yoshida was one of the artists who moved soil to execute Nobuo Sekine’s 1968 Phase–Mother Earth: a work often cited as the origin of Mono-ha, a Japanese artistic movement that advocated for a retreat from expression. Instead of using materials to convey a sense of the artist’s self or concept, Mono-ha artists created situations and juxtapositions – often pairing familiar industrial and organic materials – that allowed viewers to see an object as a ‘thing’ before seeing it as an artwork. This important show features Yoshida’s earliest Mono-ha sculpture, Cut-off (paper weight) (1969), a 250 × 210 centimetre sheet of paper weighed down in four corners with rocks and recreated based on his production notes, which he kept from April 1966 to August 1999. Yoshida’s intention, expressed in his notes, was that we see the rock anew once placed in a new context and situation. He could not have foreseen how the work might be affected by its display some 50 years later in an exhibition space located next to a stationary cycling studio blaring dance music.

‘Sōetsu Yanagi and the Korean Folk Art Museum’ | Japan Folk Crafts Museum | 15 June – 25 August

Sōetsu Yanagi’s encounters with ceramics in Korea inspired him to create the Mingei movement and cofound the Korean Folk Art Museum in 1924. In 1936 he established the Japan Folk Crafts Museum, where exhibitiongoers can now be treated to a selection from the museum’s beautiful collection of objects ranging from brooms to ceramics, kimonos to pillows, and scroll paintings to ashtrays, along with many broken pieces of pottery. Yanagi’s ‘discovery’ of Korean ceramics is intertwined with Japan’s colonization of Korea from 1910 to 1945. Japan studies scholar Yuko Kikuchi has shown that Yanagi’s position was deeply ambivalent and susceptible to colonialist condescension and nationalism. The lack of any such contextualization here is deeply troubling, but also a part of the programme. The only information accompanying the objects is given in hand-painted kanji signs that at most identify the object and indicate the period and place of origin. Yanagi underscored the importance of ‘direct insight’ in appreciating objects. I abhor the erasure of colonial context but respect the insistence on opacity.

Main image: Theaster Gates, Black Vessels for Doric Temple, (2022–23), and others. Courtesy: Mori Art Museum and the artist; photograph: Koroda Takeru