Crystal Balls, Red Light Spectacle and a Pop Art Nun: the Best Shows in Los Angeles

As the inaugural Frieze Los Angeles opens this week, here are the exhibitions you shouldn’t miss across the city

As the inaugural Frieze Los Angeles opens this week, here are the exhibitions you shouldn’t miss across the city

Kelly Akashi: ‘Figure Shifter’

François Ghebaly

2 February–10 March

Stare into Kelly Akashi’s ethereal glass orbs and gently trickling fountains and sink into a realm permeated by celestial, spectral sheen. Cast hands and graceful glass blown forms swell, descend, and shrivel in the artist’s exhibition ‘Figure Shifter’. These forms seem to reflect our own appendages – a palm prostrate, its outstretched recumbent digits curled in leisure or repose. Here, there is an odd beauty in the curvature of a thumb wrinkle. Fingers dip into sleek bulbous vessels, a louche touch balanced and lingering on the artist’s vaguely anthropomorphic silhouettes.

Akashi’s objects are not simply appealing in their sheen, but provocative shapes that seep into globs and form puddles at once uncanny, appealing, and familiar. In Flowing Figure (2019), water dribbles out of a glass conch pump into an upturned bronze umbrella, an unlikely fountain both sputtering and beautiful. Elsewhere intricately patterned glass orbs descend from thin twine, they resemble heavy lesions or internal organs that allude to the tug of gravity and of time. Bright chromogenic photograms present scans of her glass blown forns that appear as fragments of flora and fauna rendered as floating outlines or abstracted studies of paleontology. The show is a whisper, a satisfying secret where the swells and tiny knots on a sea shell, the protruding root and of a shriveled onion, and the contorted whorl of a lump of speckled glass seem to offer up all the marvel of a crystal ball.

Trulee Hall: ‘The Other and Otherwise’

Maccarone

26 January–2 March

Have you ever woken in a cold sweat from a nightmare, that, on trying to fall back to sleep, was appealing and curious in a bewildering way? Trulee Hall’s ‘The Other and Otherwise’ is a balletic, cacophonous, hallucination of painting, sculpture, installation, and video that is part nightmare, part chicken with its head cut off, and part feminist rumination on gender, sexuality, and the ordering (and disordering) of each. Hall’s exhibition lends itself to the landscape of a stage, where one is both viewer and actor, moving among the wild scenery. Enter Act I through a rounded moon gate vestibule flanked by larger-than-life golden female forms with rounded heavy bottoms and buxom chests (Golden Corn Entryway with Boob Fountain, 2018). In the antechamber, freestanding wall breasts spout water from nipple fountains. The walls are alive with clever symbols of fertility and the phallic. Among the varied kaleidoscopic works, pony tails jounce and butt cheeks quiver – the beat of the drummer at once erotic, absurd, and outlandish. Hall’s ingenuity lies in her facility to straddle each. Cue the final act, where a motorized cob of corn (Sweet Peeper, 2018) pokes its way out of the gallery wall, a cheeky sexual awakening that chips away at the very infrastructure of the gallery.

Corita Kent and Matt Keegan: ‘I Wish to Communicate With You’

Potts

13 January–14 April

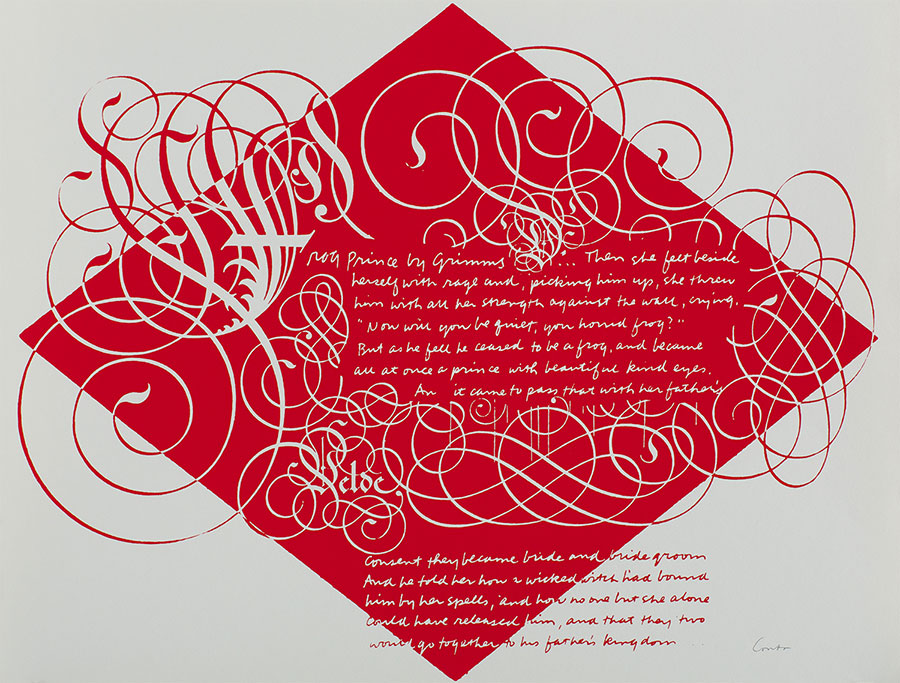

Sister Corita Kent (1918-1986) was a nun-turned-artist best known for her silk screen printed serigraphs characterized by their graphic originality and cogent political messages of her era. Kent’s interest in the iconographical and representational came to a head in her 26-serigraph A-Z series ‘International Signal Code Alphabet’ (1968), a novel reinterpretation of the International Code of Signals used by maritime vessels to communicate via flag, radiotelegraphy, semaphore, etc. While her alphabetical flags mimic the broad swaths and stripes of typical ensigns and banners, they likewise adopt positive and simple quotes, curlicue sketches, and the iconography of old-fashioned literary lettering. The flag for H professes ‘H is for my heart’ where Kent doodles fanciful faces in red and white lettering. Other letters and the words and images she chooses to include (‘E is for everyone,’ ‘F is for frog prince,’ ‘P is for palm,’ ‘S is for saint,’ etc.) speak to Kent’s own life and devotion to the power of language to communicate.

Taking cues from the palette, technique, and methodology of Kent’s flag system in folded and cut out paper form, contemporary artist Matt Keegan revitalizes Kent’s objective of utilizing flags, lettering, and the like as an efficient system of communication. Keegan’s 26 similarly hued silkscreened paper works entitled Cutouts (c is for Corita) (2018) are presented above and below Kent’s flags, where a compelling juxtaposition – or conversation through space and time – comes to the fore.

Pierre Guyotat and Christoph von Weyhe: ‘Scenes and Stages’

The Box

2 February–30 March

In ‘Scenes and Stages’ Pierre Guyotat’s half-dressed creatures of the night peer out of elongated windows, congregating citizens of the red-light district spectacle. Swaths of pink and reddish flesh encircled by flecks of dark hair appear throughout the artist and author’s drawings, perverted scenes that prey on the ribald escapades and fantasies some partake in after dark. Here, we are rendered unwitting voyeurs. Guyotat’s flagrant impulses permeate his writings, which have been historically censored for their intense carnal brutality. In one work, the artist depicts a street fight with spilled blood on the cobblestone and a sea of nude and near nude men either scrambling or oblivious to the filth and violence (Untitled, 2017). Yet these characters read as studies of men he has known, of streets he has passed, fragmented memories like a floating fistful of cash, a (sacred) offering to this infinitude of bodies.

In another room, Christoph von Weyhe depicts a wholly different frame of reference for the night: dark and bewitching scenes of the Port of Hamburg devoid of figures. His painted angular lines and shapes are at once abstract configurations and distinguishable forms like a street light cast on the water, the outline of a floating crane, or cantilevered scaffolding. In his ethereal scenes, the harbour is not merely a site of passage, of trade, of transition, but a site of lingering and of reflection.

‘Time is Running Out of Time: Experimental Film and Video from the L.A. Rebellion and Today’

Art + Practice

2 February–14 September

‘Time is Running Out of Time’ collapses filmic time, layering and collaging African American narrative and experimental cinema from the 1970s to today into a thoughtful composite portrait of history, the quotidian, and the imagined. The exhibition takes its roots in the formative values of the L.A. Rebellion filmmakers, a core group of artists that formed out of the UCLA film programme in the 1960s–80s whose work is characterized by its portrayal of everyday life in African American communities. Their documentary and experimental work from this era is celebrated for its sensitivity to relevant social and political issues and its resistance to mainstream cinematic influence. These same conventions reverberate in the film works of younger artists working today.

The astute exhibition is rife with archival material from African and African American history – from recognizable political figures to pop culture television clips and interviews with contemporary practising artists. In Ben Caldwell’s Medea (1973) images of African ancestors in regal headdresses rapidly flash across the screen, followed by a woman at church, Martin Luther King Junior, a sign for a segregated doctor’s office, and many more black and white photographs; this is 20th-century black culture spinning in orbit. In the same video, Caldwell inserts footage of a pregnant woman about to give the birth – her baby will inherit the weight of these images, along with their cultural narratives and social implications. Works by younger artists like Martine Syms’ video My Only Idol Is Reality (2017) dwells on black subjectivity as it manifests in pop culture. Syms presents re-recorded footage of the first season of the popular reality television programme The Real World (1992), isolating a verbal dispute between a black man and a white woman about opportunity and skin colour. The garbled, blurry footage loops, abstracting this already complex work of social critique.

Alima Lee and Mandy Harris Williams’ insightful Portals 1: Ja’Tovia Gary (2018) amplifies the voice of their subject, a young African American woman who speaks freely and joyously about her filmmaking practice, heartbreak, and feeling isolated from contemporary American current events while abroad. Their subject, presented on occasion in filtered, faded, and blurry hues, is likewise politicized, a woman who declares her need to take up space and be visible. So many collective narratives converge on these screens, a celebration of varying forms of cross generational celebration and resistance.

Jamilah Sabur: ‘Un chemin escarpé / A steep path’

Hammer Museum

19 January–5 May

How do you measure the curvature and angle of a descending wave? And, what of an ocean floor’s contents and the stories and lives of those who have traversed its watery pathways over time? Jamilah Sabur immerses viewers in her native Caribbean landscape – a dry sandy bank, a cloudy mountain range, a marshland with tall gently swaying grass. These visually striking outdoor scenes unfold over a 5-channel video installation Un chemin escarpé / A steep path (2018) that explores her island homeland and the politics of its borders, colonial history, and its social and global integration. One settles into the artist’s immersive mise-en-scène, surrounded by the faint blue glow of the monitors.

The Caribbean landscape that Sabur depicts appear as many sites at once, a wide panorama here or a closely cropped embankment elsewhere. The artist herself emerges from the scenery, a costumed figure in a traditional white cricket uniform or donning a mask and worker’s gloves. She performs idiosyncratic dances in these scenes, balancing on a thin wooden beam she carries along a wet meadow. In another scene, she rocks a wooden rhomboid frame – a personal reference to her mother and with that, to her motherland. This apparatus resembles an old-fashioned cartographer’s tool. Yet Sabur reframes its use by planting this object in the sand and kneeling before it in a ritualistic-like gesture of worship and reverence for this land.

Nancy Shaver and Emi Winter

Parker Gallery

3 February–30 March

A lone sock resting on a wood and fabric patchwork box is a humorous 3-dimensional trompe l’oeil, a garment one might mistake for the real thing. Nancy Shaver’s Flat Goods (2006) and other sculptural works in ‘Gathering Texture, Following Shape: Nancy Shaver and Emi Winter’ are comprised of the ‘the real thing’ – found dress fabric, wooden spools, and other playful bric-a-brac. Her sculptures seem to take on multiple lives, where cast off detritus is revivified as material and readymade pattern. While many sculptures recall grandma’s beloved floral loveseat, one aberrant work (Sentinel, 2018) repurposes a faded wrestling character t-shirt. Installed before the house gallery fireplace beside the more decorative pieces, Shaver’s fabric character opens his mouth in a tough guy scream and flexes his giant muscles. The shadows and contours of his body are cracked and peeling, a mark of time that likewise references the gradual decay of the body.

Nearby, Emi Winter’s traditional Zapotec patterned rugs grace the gallery floor, objects that straddle the space of utility and ornament and that eventually, like a sock, will wear out. Like Winter, however, Shaver fragments these traditional designs, selecting parts of patterns to create unusual, striking geometric designs. Both artists use the texture and material of the conventional to subvert it.

Main image: Corita Kent, c is for clowns etc., 1968, serigraph, 45 x 58 cm. Courtesy: the artist, Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community and POTTS, Los Angeles