Curating by Numbers: How Budgets Shape Exhibitions

Hans Ulrich Obrist's collection Think Like Clouds highlights the logistical evolution of the curator’s role

Hans Ulrich Obrist's collection Think Like Clouds highlights the logistical evolution of the curator’s role

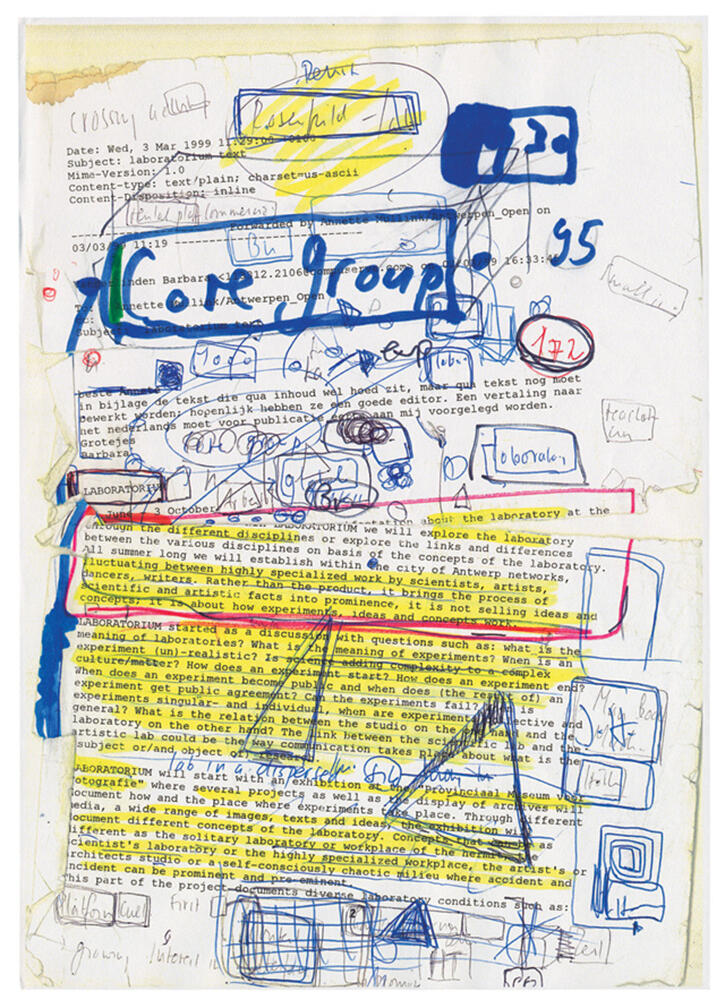

Last September, Badlands Unlimited, the New York-based publishing house set up by artist Paul Chan, announced a new project. Think Like Clouds (2013) collects 22 years’ worth of notes, drawings and diagrams by cultural marathon-man and Serpentine Gallery co-director Hans Ulrich Obrist. Available as a paperback or an e-book (because, as the Badlands website notes, ‘you can’t publish a .gif on paper’), Think Like Clouds risks playing into the popular impression of curating as a somewhat opaque profession. After all, if you type ‘what do curators …’ into Google, the search engine suggests that you complete the question with ‘actually do’ (the second suggestion is ‘wear’).

But what do these frenetic sheets of paper actually say about Obrist’s inner workings? The book’s title has an echo of 1990s-era ‘blue-sky thinking’, while the anxious lists of names and themes, many of which are almost illegible (does that say ‘finance’ or ‘trauma’?), conjure up the rather outmoded image of a curator as the gifted connector of artists and ideas. Although these qualities might remain important to the practice, I wonder if keywords are really what predominate in curatorial thought today, especially for those working in smaller spaces or outside of major cities, where resources are so limited. Indeed, ‘Rebalancing Our Cultural Capital’, a report published by Peter Stark, Christopher Gordon and David Powell last October, indicates that central government spending per capita on culture in London in 2012–13 was nearly 15 times greater than in the rest of England. And while this interpretation has been criticized as an over-simplification by the Arts Council and others, it’s hard to refute the broader picture of uneven national investment.

Little has been written in the art world about the calculations that course through a curator’s mind. Perhaps because the logistical concerns that they represent are seen to sully the seductive image of the arts as safeguarded from such mundanity. In a conversation about the proliferation of curatorial studies programmes (published in this magazine in September 2011), Chisenhale Gallery director Polly Staple pointed out that ‘curating’ comes about ‘through structural decisions about how the institution operates, how the artistic programme is produced and how you engage with audiences. I also spend approximately 80 percent of my time fundraising. I don’t think they talk about that much in curating school.’ This issue is particularly topical in the UK right now, given that the three-month window for applications to the Arts Council National Portfolio and Major Partner Museum funding is about to close; many wait with bated breath for the July announcement of how the five percent cut will be introduced across the organizations that it supports.

Of course, budgets account for only a fraction of the numbers that curators have on the brain. Thoughts swarm about the details of an art work, its dimensions and accession number; technical specifications for a projector; image resolution; security requirements and insurance values; conservation concerns, including light levels and humidity; the accessibility of facilities, such as the width of doorways or the maximum weight of a stair lift; visitor numbers – the list is endless. And the problem with numbers is that they tend to produce a kind of butterfly effect: even relatively small increases in spending can squeeze an organization’s ability to make the other numbers balance. If an insurance company requires toughened glass for a display case to be 10mm rather than 5mm thick, then the weight of the sheet will double from 30kg to 60kg and the number of staff required to lift it becomes two rather than one. Suddenly you have a dramatically different installation cost. When relatively minor details can have considerable consequences, how can curators afford to take their eyes off the numerical ball?

In art-world mythology, the curator’s pedantry is a necessary foil to the artist’s bohemian disarray – terms like genius or éclat suggest a burgeoning forth of work, but not the details of its subsequent presentation. A key difference in recent decades has been the elaboration of security and conservation requirements. Lucy Lippard has noted how, in 1969, her ‘lack of training and lack of respect for the ubiquitous white gloves’ meant that she could install her famous ‘Numbers’ exhibitions with ‘as little baggage as the artists’. Nowadays, though, expectations have become so exacting that the Bizot Group of international museum directors, led by Nicholas Serota, has been arguing for ‘international guidelines incorporating a broader range of conditions’. In this context, Khaled Hourani’s Picasso in Palestine (2009–11) project – a two-year struggle to agree the loan of Picasso’s Buste de Femme (1943) from the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven to the International Academy of Art Palestine in Ramallah – made visible the administrative acrobatics that so often go unseen beneath the network of global loans.

Perhaps the most controversial of the numbers that prey on curators’ minds are those relating to visitors, not least because of inconsistencies in how such data is collected and the inadequacy of these statistics when it comes to the nature or degree of audience engagement. The more arts professionals are forced to gather such numbers (primarily to justify expenditure to funders and patrons), the more they risk becoming seduced by their own data, believing that attendance is an end in and of itself. As Tom Sutcliffe argued last year in The Independent, in response to the announcement that Tate Modern had attracted 5.3 million visitors in 2012, the problem is not really the digital sensors that record these numbers (since most people, including the Department of Culture, Media and Sport, recognize the difficulty in achieving accuracy), but the fact that a ‘9.5 percent increase in the figures doesn’t easily correlate to an enlargement of the national contentment or refinement or sensibility […] it’s worth remembering that every million extra visitors a gallery gets may well be accompanied by a matching dilution of the collective looking and thinking actually done in that building’.

So what’s the sum of all of these numbers? Collectively, they represent a positive evolution of the curator’s role, which began with the dismantling of the divide between those who ‘select’ and those who ‘organize’ exhibitions, and has continued with an expectation that curators should have a holistic involvement in all aspects of their programmes. With continuing cuts and diminishing staff (a Museums Association survey found that, between July 2012 and July 2013, 37 percent of respondents had been forced to make redundancies), the pressure is on. Yet demonstrating creativity in the face of constraint – whether conceptual, architectural or financial – has long been at the core of curatorial practice, so perhaps it’s simply time to acknowledge this artful arithmetic.

In the brilliant trailer for Obrist’s Think Like Clouds, made by the young New York-based artist Ian Cheng, a digitally rendered image of the curator’s head talks feverish nonsense, while jerking against a landscape of old video games, in time to a mash-up of ‘Head Like a Hole’ (1990) by Nine Inch Nails. About 20 seconds in, the backdrop morphs into a Minesweeper grid and a cursor begins uncovering the classic 1s, 2s, 3s and 4s that indicate the proximity of a mine. Freeze the video here and you have a more apt image of the curator’s imagination: wallpapered with numbers and strategizing against imminent threat.

Main image: Page from Hans Ulrich Obrist, Think Like Clouds, 2013. Courtesy: Badlands Unlimited