Daniel Sinsel Plays Hide and Seek

Moving between concealment and display, the artist treads a fine line between seduction and deception

Moving between concealment and display, the artist treads a fine line between seduction and deception

There is an anecdote in the memoirist James Lord’s famous account of sitting for Alberto Giacometti in which the artist accidentally kicks the easel and instinctively apologizes to his sitter.¹ The episode has the illustrative feel of a parable, and this is how it is often retold: the studio-bound artist takes the painting itself for the person or object being painted. Giacometti’s apology suggests that, in the studio at least, the umbilical connection between sitter and painting is never fully severed. The accidental kick that punctuates the encounter reveals the worry that – like Dorian Gray, only in reverse – the subject may never be quite immune from the scuffs and scrapes suffered by his likeness.

This is one of many anxieties played out in the paintings and carefully adorned miniatures that Daniel Sinsel was making around the time he graduated from London’s Royal College of Art in 2004. These icon-like works depict naked and semi-clad young men who float against depthless planes of vibrant colour. Toned, angelic and barely legal, some are obviously taken from the more corn-fed end of the gay porn market, while others – slender and diffident – are perhaps friends of the artist; whatever the neoclassical echoes we see in these portraits or nudes, these men belong to a specific part of the contemporary world. In an interview given in 2005, the Munich-born Sinsel, who has lived in London since the late 1990s, made a passing mention of his interest in the ‘latent eroticism of neoclassical painting’.² In his own work eroticism is not so much latent as claustrophobic, bounded by airless backgrounds or chunky grids that offer no way out. What’s more, the three-ways that these early works construct – between sitter, viewer and frisky young artist – are laden with an implication of violence rather more vicious than an upended easel. The anonymous models in these quasi-devotional works are paired or substituted with suggestively cocked pen-knives; they are sometimes scarred, as in Untitled (man, ribbon, knives) (2004), and often bleeding. Intimacy and the desiring gaze become the unwitting consorts of something darker.

Sinsel’s exhibitions, like his works, have almost always gone untitled, though his 2007 show at Sadie Coles HQ in London was given the German name ‘Grete, erregt’ (‘Grete excited’ or ‘agitated’) – the reference is to the Grimm brothers’ tale of Hansel and Gretel, a story which Sinsel has called ‘erotically entertaining’.³ Food is central to three of the narrative’s sinister scenes: the children first become lost in a forest after their trail of breadcrumbs is eaten by birds; hungry and abandoned, they find a cottage made of gingerbread; inside lives a short-sighted witch who the children trick using chicken bones as stand-ins for their own well-fed arms. Food is figured as at once nourishing and untrustworthy, a tool for tricks and deception. It doesn’t bode well that the young men in Sinsel’s earlier paintings often sit alongside different fruit and vegetables: rosehips, a radish or a slice of an orange float close by – symmetries that each carry an echo of heraldic significance. The models are often just dupes in a game of implication or substitution: a long radicchio stands erect against an inky flat background; a pouting model – arms and legs truncated like a damaged statue – has a pair of hazelnuts painted over his bleached-out crotch (this bawdy association of nuts with virility is not a one-off).

These assembled images – life-sized and usually presented within arm’s reach – insinuate the possibility of acquisition. They are part of a still-life tradition in which the language of perception and representation is wrapped up with that of ownership. We say that the artist ‘captures’ a likeness, after all, or that we ‘grasp’ the likeness between an object and its representation. However abstract, Sinsel’s paintings never fully abandon human scale and they are full of graspable, hand-sized things. Pocket-knives, vegetables, musical instruments, not to mention penises – these are sometimes tempting but never quite unthreatening.

The equivalent delectations of foodstuffs and bared flesh have lately taken the form of other optical snares in works that are less concerned with a queering of neoclassicism or in the figure of the horny young painter. These can be trap-like in their intention to seduce or to deceive. Sinsel mentioned to me that he sometimes conceives of the models’ heads as ‘sculptural vessels’: compliantly open-mouthed, they speak to an erotic experience but also to the more technical painterly concerns of surface, volume, light and illusion.4 He achieves remarkably various effects with paintings in oil on linen: in an untitled diptych from 2009, for example, two parabolas of x-shaped insertions seem to be made through dull-finished aluminium, the surface fading from a jaundiced yellow to a queasy rose-pink. The suggestion of a punctured metallic support, rather than a linen one, implies a very different kind of force exerted on the picture plane – one that is involves a prying open of a tough material rather than a slicing into the canvas’s flesh. Our perception of violence inflicted is delivered by associative degrees: paintings of knives are replaced with their apparent marks.

The best-known examples of trompe l’oeil exploit our easy familiarity with looking at pictures: Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts’ 1670 painting that appears to have been turned to face the wall, or Parrhasius of Ephesus’s rendering of tattered curtains apparently thrown across his painting made in the 5th century BCE. Just like those Oscar-bound performances that seem to say ‘look, I am acting’, emphasizing the hard graft of simulation, the classic trompe l’oeil painting makes only a fleeting attempt to deceive. Once the game is up it’s eager to draw attention to its own virtuosity. Sinsel’s own illusionistic techniques usually refer to the thinness of the canvas and its potential to be cut into rather than to the trappings of traditional display. His recent work has often included a painted slash that runs from corner to corner, the canvas seeming to curving inwards to reveal a sliver of blackness. These diagonal slits take the place of the earlier structuring element of the knife or erection. These trompe l’oeil slashes quote Lucio Fontana, of course, but where the Italian artist’s ‘Concetto spaziale’ series (Spatial Concept, 1949–68) asks the viewer to look beyond the physical fact of the canvas, Sinsel’s slashes emphasize its surface. These schematic marks rework the artist’s gesture as a quickly executed violent act, speaking instead of diligent time spent looking and working in the studio, while at the same time directing our attention back to what the artist’s hand is doing to the canvas. The act becomes alchemical rather than violent; like paintings, illusions are always a matter of time and timing.

Since 2003, Sinsel has painted the motif of a flute or pipe, which he sees as an efficient device for crossing (and crossing out) the surface.5 What’s curious is that despite the variousness of its appearances – blurred, doubled, with spikes – it is never completely elaborated into a working instrument: the ‘pipe’ is solid rather than hollow, lacking the required mouthpiece and finger-holes. In Sinsel’s current exhibition at the Chisenhale Gallery in London – his first solo show in a public gallery – a 22-carat gold pipe is set in a diagonal recess within a Modernist-style display unit. Glance to an adjacent black and white photo collage, of three similarly scaled sticks held between three pairs of buttocks, and the frame’s linen-covered curves seem to take human form. The obviously phallic pipe does what several related sculptural objects also do, which is to put a human-scaled instrument outside of human use. The results are comically hybrid, coining formal rhymes between body parts and musical instruments: the tapering lower end of an aluminium cast of a pipe from a church organ is intersected with a calf muscle or, more jarringly, the centre of a suspended terracotta cymbal morphs into a pendulous scrotum.

If Fontana’s arrow-straight slashes depend on the tension of the stretched canvas to hold the sliced plane taut, many of Sinsel’s recent works are involved with what happens once the support is removed. The first of his ‘date pieces’ is poster-sized and reads ‘2009’, cut into the top layer of layered linen, the numbers’ sagging curves looking a little mournful, as though they were missing the frame. A second, made last year, has a similarly flaccid, downward motion: it is an oil on canvas rendering of ‘2010’ based on the date cut into a grid of yellow pasta dough. The rumpled layers, somewhere between drapery and flesh, make the numbers all but illegible. Sinsel has also begun to use rough silk, which – with the help of several friends over the course of weeks – he hand-weaves into seamless tubes. At the Chisenhale is a wall-mounted silken archway. This soft approximation of architecture hangs from metal supports, and is echoed by a pair of columns in an untitled 2011 painting that frame what looks a yellow Fontana.

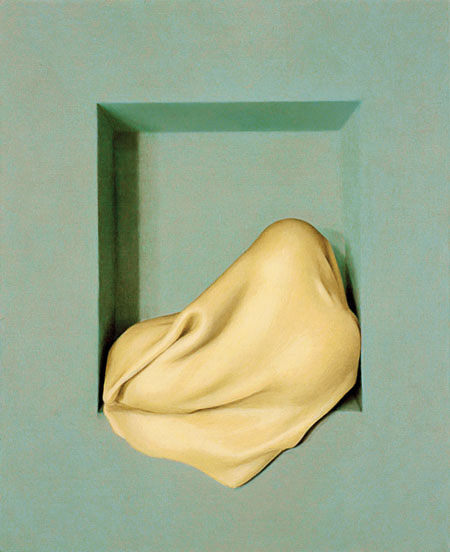

The spaces here comprise architectural elements, from archways and alcoves to chunky marble grids, but the objects that they frame are insistently corporeal as are the canvases. In an untitled work made earlier this year, for example, nutshells have been pushed under the weave of a linen piece to create a dozen small, bulbous protrusions in its tarred surface. The body parts in Sinsel’s recent paintings are not brightly lit and exposed, but draped with pastry or fabric. In an untitled oil painting from 2008, a muted green recess holds what could be a swaddled cock and balls (the artist, in a neat example of the vegetable/eroticism binary, has revealed that it was actually a parsnip wrapped in pastry). Sinsel’s work remains haunted by the same anxiety as those early nudes – that the gaze is capable of damage. Human form is both carefully covered and clung to, as though that’s the only way to keep it safe from harm.

1. James Lord, A Giacometti Portrait, New York, 1993, p.37

2. Daniel Sinsel, Sadie Coles HQ, London, 2005, p.12

3. Ibid.

4. In conversation with the writer, 23 January 2011

5. Ibid.