Denzil Forrester: ‘I Had to Find Something That Shook Me Up’

With a recent show at Stephen Friedman Gallery, the Grenadian-born British artist talks to Osei Bonsu about painting, London's 1980s club scene and moving to Cornwall

With a recent show at Stephen Friedman Gallery, the Grenadian-born British artist talks to Osei Bonsu about painting, London's 1980s club scene and moving to Cornwall

As the culture wars of the 1980s raged, the Grenadian-born, British artist Denzil Forrester found refuge in the dimly lit dancehalls of London’s underground nightclubs. Armed with his drawing materials, he sought to capture the enigmatic energy of the dub and reggae music scene and the people it attracted. Fixated by the transcendental power of legendary DJs such as Jah Shaka, famed for his ability to fuse spiritual energies with the explosive sonority of his signature sound system, Forrester would sketch for the duration of a record. In the resultant large-scale paintings, ecstatic bodies gather and disperse across crowded dance floors, throwing abstract shapes across the brightly coloured surface of the canvas.

Beneath the high-spirited jubilance of these early works hums the sombre reality of life for the Windrush generation (migrants who arrived in Britain after 1948 from the Caribbean on the SS Empire Windrush). Forrester’s celebration of the vibrancy of Caribbean culture is inseparable from the struggles of assimilation and institutional racism. Shaken by the brutal death in police custody of his friend Winston Rose in 1981, for some years, the artist focused almost exclusively on ‘police paintings’ that portray a community under the constant threat of violence and persecution. A masterful synthesizer of pictorial languages and art-historical references, Forrester creates paintings that are as much documents of our times as they are experiments in gesture, light and colour set to the rhythm of Black music. While the beaches of Grenada are a far reach from the Cornish coast where he now resides, Forrester remains inspired by music and its ability to colour the world anew.

Osei Bonsu As one of the pioneering figures of the Black British arts movement in the 1980s, whose art is now enjoying a resurgence in popularity, why do you think it has taken people this long to recognize the importance of your work?

Denzil Forrester In 2015, [the artist] Peter Doig sent me an email asking if I wanted to do an exhibition and, since then, everything has taken off. I’ve had shows at Tramps [Doig’s gallery] in Shoreditch, east London, and at White Columns in New York. In 2016, I moved to Cornwall, where I had a show, ‘From Trench Town to Porthtowan’ at Jackson Foundation in 2018. It’s a lovely, big gallery in St Just, which is almost at Land’s End. Everyone from London came and, suddenly, things took off again!

I’ve been painting for 40 years. I finished at the Royal College of Arts in 1983 and then went to Italy for two years on a Rome Scholarship. I came back to London in 1985, but then I relocated to New York for two years after receiving a Harkness Scholarship. By the time I came back, the yBas [Young British Artists] had taken over and it seemed that people were mainly interested in installation-based work and more conceptual ideas. If you were a painter, you didn’t stand a chance! So, I taught for 30 years, three days a week, and focused on painting the rest of the time. I had just enough money to live. I thought: ‘I’ll just keep going and see what happens.’

OB During your time at the Royal College, you visited museums and galleries throughout Europe. Which artworks influenced you at the time?

DF My arts education was brilliant because I had great tutors. One of the best was the late Peter de Francia, the French-born British artist. He saw the potential of my work and made sure I had everything I needed. But, of course, this was art school in its heyday when there were big studios and lots of money. We used to travel at least two or three times a year, mainly to Paris and Amsterdam. In the 1970s, when I was doing my BA at Central School of Art, I went to Paris and came across Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne for the first time. I remember discovering Vincent van Gogh when we went to Amsterdam and visited the Kröller-Müller Museum just outside of the city.

These artists helped get me motivated about the dynamism of painting. Most of my contemporaries at art school were interested in North American abstract expressionism, but I knew that I had to find something that shook me up and stirred me from within. In the 1980s, I began drawing in nightclubs like Phebes in Dalston, because I realized that Monet’s waterlilies and Van Gogh’s landscapes were motivated by something simple: painting itself. You have to paint something that means something to you. You might have the knowledge, the skill and the craft, but if it doesn’t mean anything to you, painting loses its totality. That’s how interesting artworks come about, from something that’s deep within you.

OB What was it about the atmosphere of these nightclubs that inspired you?

DF The main DJ to follow was Jah Shaka. He had a big sound system, which was very rare at the time. It wasn’t a stereo, which is circular, but a mono system, like a punchbag, which is ideal for the reggae-dub sound. The music and the sound were important. The majority of the crowd was Rastafarian; they came dressed in incredible headgear and clothes. To capture that energy was important – just being there and making drawings in that space and time. When I got back to the studio to paint, I would have about four or five drawings that I might use to re-create that sense of being there, but the energy of the nightclub came from within. If I hadn’t been there, I wouldn’t have been able to transfer that energy because it’s not just visual, it overtakes you and sustains you.

When I was in Rome, I used all the ideas and ammunition I had gathered in London to make these big paintings. What I got from the city was an understanding of light and colour, especially because London was so dark and grey. The colour was always there in my work, but if you live in a place like Rome you can’t help but paint colours a lot clearer and sharper. I was born in the West Indies and I think the light there is probably even better than in Rome. The first painting I did in Rome was Carnival Jab (1983); I wanted to mix the atmosphere of Notting Hill Carnival with the nightclub dub. On the left-hand side of the painting, I introduced a fountain because I was influenced by Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s beautiful fountains in the Piazza Navona in Rome, which feature these big, muscular figures messing about. I took one of them and turned it into a Rastafarian. It was like a Shaka sound system; once it was set up, you could have fun all night. Being in Rome freed me up and then all the paintings just happened

OB How did the nightclub crowds relate to you as an artist?

DF Phebes was only a ten-minute walk from my house. The Rastafarians were interested in arts and crafts, not just music; I think this is why I was allowed in with my drawing materials because, if you are an artist, they really ‘big you up’. The club was divided into two sections: the disco part and the basement, which was for the reggae-dub scene. I would start in the disco section; it was quite relaxed, with a big dance hall, and I’d sit near the stage. When you’re an artist in a public arena, you have to be dynamic. I wasn’t interested in just drawing an individual standing in front of me; I was interested in capturing the energy of the whole room.

Come midnight or 1am, Shaka would play in the basement, so I would go downstairs. The room would get completely crowded: the only place I could draw was on the counter of the bar. I was happy and uplifted when I went to those clubs because there was connection between me and those people. Most of them came to London in the 1960s from the Caribbean – a place with green grass and sunshine, where people live most of their lives outside. In London, people lived in dark, dingy houses and worked a lot. The weekend was like freedom. You could sense it; you could smell it; you could taste it in the air. It was the only time people could free themselves up, enjoy the spirit of life.

OB You came from Grenada to London’s Stoke Newington in 1967 as a child, just after the Windrush generation. What do you remember about arriving in Britain?

DF When I was a kid, carnival was the most important thing in my country. Every weekend, you’d go to the Junction [bar in Grenada] and listen to musicians play steel-band music and dance under the moon and stars. When you came to London, that focus was gone. That’s when the rocksteady parties began. Before dub, there was rocksteady in the 1960s and ’70s. It was just normal reggae, with no messing about, no dub, no scratching, no feedback, none of that. In the West Indies, they used to have house parties; you’d have your old gramophone, with twin speakers and drinks in the middle. The rocksteady house parties were brilliant because people danced and huddled up close together. There was a feeling of togetherness over curried goat, rice and peas, and long life.

The Windrush generation would have had rocksteady parties, but my generation were the ones who started the dub scene. The Grenadians lived in Shepherd’s Bush, but my mum didn’t want to go and live with the Grenadians. She wanted to live with the Jamaicans in Hackney. These areas were making up for the loss of old structures; we had to adapt and change. You probably wouldn’t see a lot of your family or friends living in London, so these parties actually rekindled our community spirit.

OB In 1981, your friend Winston Rose died in police custody, which prompted you to create a series of paintings depicting police brutality and surveillance. What role did painting play in the process of your mourning his death?

DF When I came to London in 1967, my mum had a two-floor flat and Winston’s family had the top floor. He lived in the same house as us for about five or six years, and we would play together. When I was at the Royal College in the 1980s, I remember watching the local news on television and seeing that Winston had been killed in police custody. At the time, I had to write a thesis, so I decided to research his death. I went to see his family to offer my condolences. I needed more information, so I went to the inquest at Waltham Forest Magistrates’ Court. Once I knew about the horrific way he died, I couldn’t get it out of my head.

I was doing a painting of Shaka at the time and, if you look at Winston Rose (1983), you’ll see a speaker on the left-hand side and a symbol in a yellowish-gold. In the middle of the painting is a coffin. In the original version, you could see Shaka and the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie [considered by Rastafarians to be the messiah incarnate], but I got rid of them and put a coffin in the painting. I’d drawn a lot of people falling asleep in nightclubs; one of the people I drew was lying on their back. I imagined Winston’s head on the stranger’s body. After that painting, I mostly made police paintings, like Three Wicked Men (1982). I could not have done these works if I hadn’t known Winston: I wouldn’t have had the energy and the feeling. I painted them like I drew the nightclub scenes, with speed and gesture. It was so horrific I didn’t want to think about it; I just needed to express it.

OB Three Wicked Men portrays three different archetypal British characters: the ‘dread’ or the rasta, the policeman and the politician. What do these recurring archetypes mean to you?

DF When I painted that work, there was a lot of ‘stop and search’ going on in London. I was focusing on what was happening to young Black guys through the figure of Winston. In order to get the empathy, the feeling and the depth, I had to use Winston because I understood how he died. When I went to New York, I did a painting called Police in Blues Club (1985) of Winston in a nightclub surrounded by endless police figures. I used mainly the head of the police and their helmet-shaped hats; they’re like dogs with their mouths open, surrounding Winston and trying to stop him from playing his records. I remember these incidents with the police in the clubs; it would be full of people dancing then, suddenly, the lights would come on and they would just walk in.

I used to do a lot of drawings of the police at the Notting Hill Carnival; they would stand in front of the speakers on the street. When I came back from the US, I thought about continuing to make paintings about police brutality. I was looking at Steve Biko, the South African anti-apartheid activist who also died in police custody, but I knew nothing about his life. It had to mean something to me; I couldn’t have made any of those paintings without knowing Winston and what happened to him.

OB What did the Rastafarian signify in Black British culture at the time?

DF The Rastafarians were hated in the West Indies because they were considered to be ‘dirty’ people who played ‘loud’ music. In fact, I think they were more loved in London than they were in places like Trench Town, Jamaica. To me, they were interesting and creative. Now, everyone loves them – Bob Marley’s house is a bloody museum! At these nightclubs, some of the guys would come dressed as African royalty. These people would spend a lot of time presenting themselves, strutting up and down the dance floor. A lot of people took on the Rasta style and it went viral. The beautiful thing about the true Rastas was that they had the walk to go with it and were very influential people within the Black community. A lot of the people who would have lived around Brixton have gone now; it is a totally different place – a lot of Black people have been pushed out.

OB It’s interesting that, at a time when the rights of Britain’s non-white citizens are being threatened by an increasingly nationalistic discourse, exemplified by the Windrush scandal, the Black arts movement of the 1980s is gaining visibility.

DF I think things are changing. A lot of Black artists who emerged during the 1980s are doing quite well. They might not be selling their work, but they still have enough space and time to practise as artists. Black people come from a very creative culture of music, dance and visual art: it’s part of our lives. When we first came to the West, these cultures were kept in museums. My parents are not interested in my work at all; they think it’s rubbish. Perhaps that’s because a lot of Black people don’t like their present-day history being told. And yet, at my family home, they’d hang up reproductions of beautiful Victorian paintings that meant sod all to them.

I don’t think most Black people want their kids to become artists, because it’s to do with giving yourself over to creativity. But art is the biggest thing you can choose to do because you’re saying: ‘I’m going to find freedom for myself’ – and no one likes that. My own culture may not support me in terms of appreciating my work, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to abandon them. My mum is a very creative woman – she used to make the best dresses for the Carnival queens in the West Indies – but when she came to London she had to make bloody old bags!

OB You mentioned moving to Cornwall in 2016. How has living by the coast changed your perspective?

DF Within London there is revival of Black culture – a kind of romanticism, really. People want to go back and look at the 1980s and use Black people’s work to do it. I’ve been making these paintings for 40 years, but now, suddenly, people want to show them.

In reggae, dub guys used to have battles by doing different versions of the same records. From that, I decided to explore making versions of my paintings. I was looking at the background of Three Wicked Men and decided to change the figures’ surroundings. Porthtowan is a lovely beach in Cornwall, but 90 percent of visitors are white. For From Trench Town to Porthtowan (2017), I thought I’d superimpose Three Wicked Men onto that beach and bring the people of London to Cornwall.

OB What excites you about painting now?

DF The filmmaker Julian Henriques showed up at my exhibition in St Just and asked if he could accompany me to Kingston, Jamaica, where I was going to draw the nightclubs. I hadn’t visited them for about 20 years but the dub scene is still very popular there. I didn’t actually know how it would be, but it was great going back. The crowd in the 1980s didn’t want to talk much; people are much more confident today. I make a drawing for the length of a record, so it’s hard work. But what I’m trying to capture in painting today isn’t very different to what I’ve been doing for the last 40 years. I’m interested in gesture as movement, action and expression. That’s why I still love going to nightclubs. You look back at your life and you realize what you like.

Denzil Forrester lives in Cornwall, UK. He had a solo show at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, UK, in May; his Transport for London Commission will be unveiled at Brixton Underground Station in September. In 2020, he will have a solo exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary, UK.

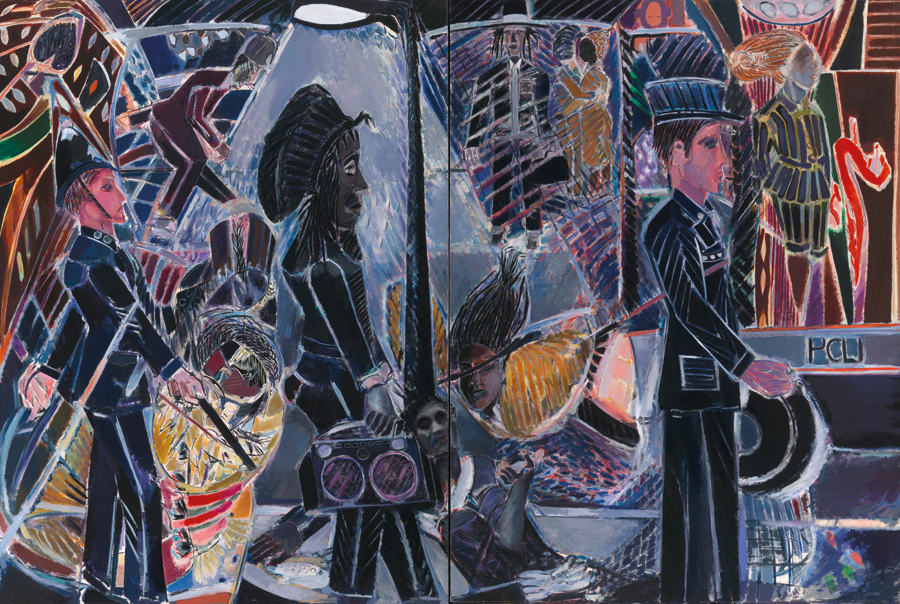

Main image: Denzil Forrester, Wolf Singer, 1984, oil on canvas, 3.4 × 4 m. Courtesy: the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

This article first appeared in frieze issue 204 with the title ‘See What Happens’