By Design

How technological developments are changing our relationship to control

How technological developments are changing our relationship to control

Baffling though it may seem to anyone who suffers the delays, overcrowded trains, broken lifts and other shortcomings of the London Underground today, it was hailed as a model of modern design in the early 20th century. Under its visionary managing director, Frank Pick, the Underground not only introduced its passengers to modernist architecture and graphic design, but pioneered mechanical innovations like electric ticket machines, escalators and pneumatic train doors. The only problem with those gizmos was that many of the passengers were too scared to use them.

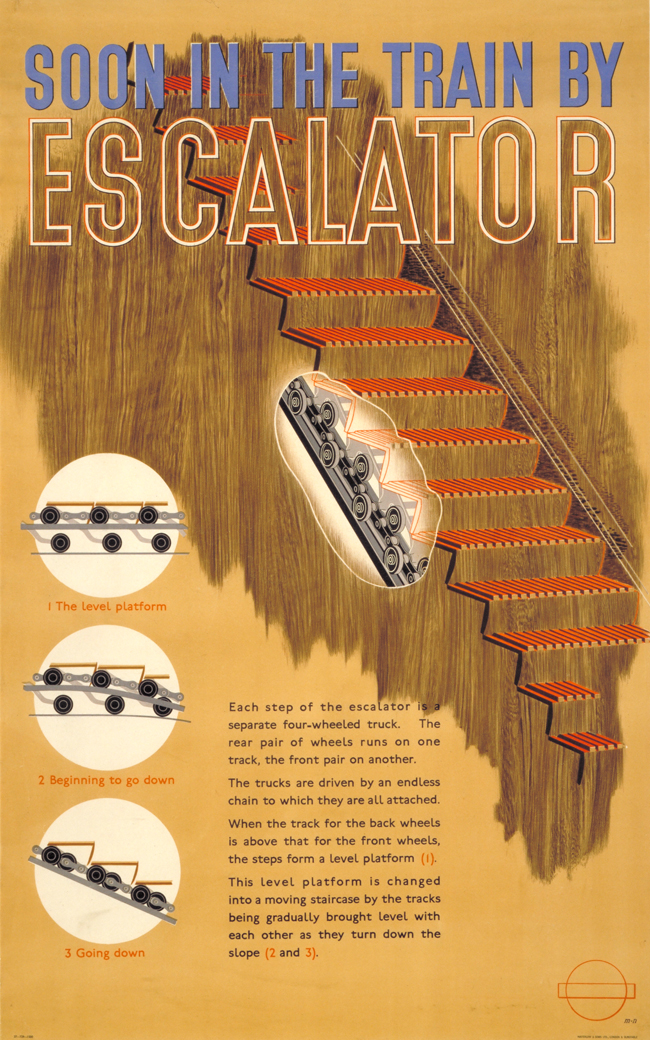

Pick and his colleagues were so concerned that, in 1937, they commissioned László Moholy-Nagy, the Hungarian artist, designer and visual theorist, to devise posters explaining why the new contraptions were not as frightening as people seemed to fear. Once a star teacher at the Bauhaus, as an émigré in London, Moholy-Nagy was reduced to scraping a living from commercial design jobs like this one. One of his posters sported the optimistic title, Soon in the Train by Escalator (1937) above an illustration of the escalator’s wooden steps with cutaway images revealing what the machinery inside looked like as a ‘level platform’, ‘beginning to go down’ and ‘going down’. A short text described how it all worked.

Soon in the Train by Escalator, which is exhibited in this summer’s Moholy-Nagy retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, fulfilled one of design’s most important, yet often unsung, roles: of helping us to adjust to changes in the logistics of daily life by dispelling our fears of them. Another of Pick’s design coups, Harry Beck’s 1933 diagrammatic map of the London Underground, enabled bemused passengers to navigate the sprawling network more efficiently than they could have done with a geographic map. Similarly, Moholy-Nagy’s poster encouraged them to glide effortlessly up the escalator from the platform to the exit, rather than dithering nervously while worrying about getting tangled up in its machinery. Both designs gave people the confidence to cede control to a potentially daunting innovation by convincing them that they understood it.

Control remains a defining element of design today, yet our relationship to it is changing radically. Many of the technologies we now use are so powerful and complex, and will become even more so in future, that any attempt to make us think we might control them would be pointless. In the age of AlphaGo, 5G circuitry, neuromorphic and quantum computing, driverless cars, artificial intelligence and other innovations that promise to take over more and more aspects of our lives, the new design challenge is to ensure that it will be in our best interests to be controlled by them and to persuade us that this is so.

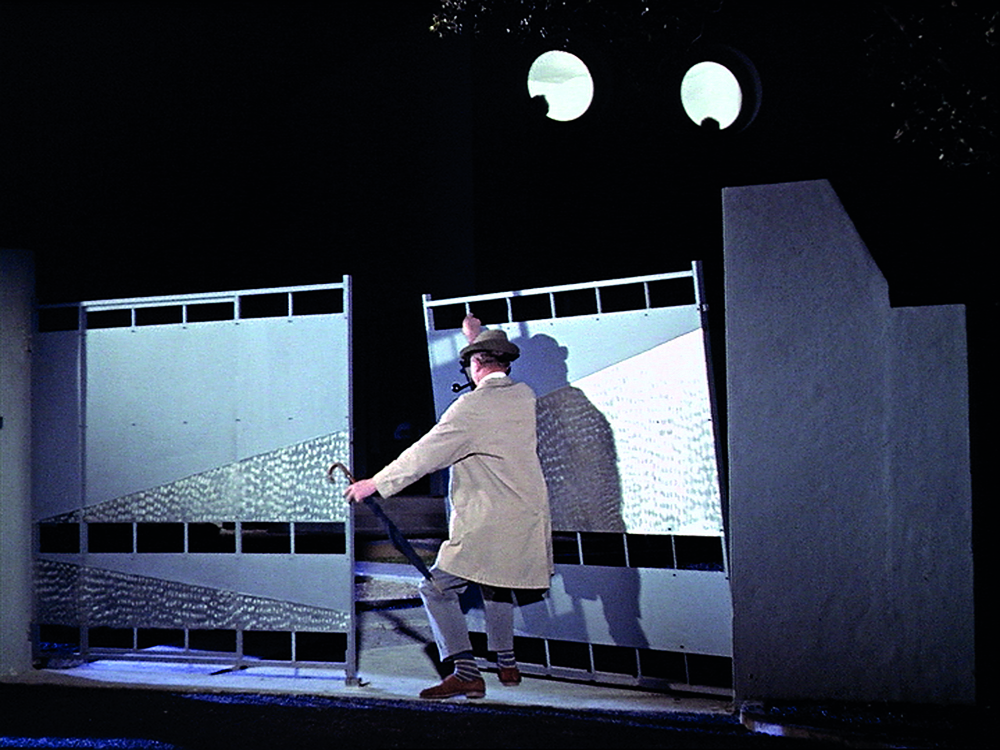

Achieving this will require a radical shift in design culture, because helping us to feel as though we were in control was the driving force of so many past design triumphs. Take the signage programmes that enabled motorists to drive swiftly and safely on newly built roads and motorways, like those designed by Margaret Calvert and Jock Kinneir in Britain in the 1960s. Or the operating systems with which people use cars, record players, television sets, computers and smart phones. When designed intelligently, they empower millions of us to conquer our fear of the new. If their design were botched, the consequences could be infuriating, as Jacques Tati’s hapless anti-hero Monsieur Hulot discovers when visiting his sister’s ultra-modern house in the film Mon Oncle (My Uncle, 1958). One by one, the house’s futuristic gizmos malfunction, from the uncontrollable electronic garage doors that open and close inexplicably, to the inscrutable kitchen gadgets.

Often, designers have tried to reconcile us to new things by suggesting that they are not so very different from familiar ones through deploying skeuomorphic design references. The wooden casing of the escalator in Moholy-Nagy’s poster served as an early example, disguising those newfangled mechanical stairs as traditional wooden ones. The same rationale explains why we type instructions to computers on old-fashioned Qwerty typewriter keyboards, and why the apps on our digital devices are often identified by images of the telephones, letters and other analogue objects that they are threatening to replace.

Designers now need to develop different approaches. One problem is that we are so adept at decoding some of the old ones, they are becoming less effective. The public debate around skeuomorphism suggests that more and more of us are so confident about using digital devices that we not only consider such cues to be superfluous, but feel patronised by seeing a paper envelope identifying the email app and a telephone handset for the phone on our supposedly state-of-the-art iPhones.

Our response to design strategies, which were once successful at helping us to deal with hazardous situations like driving or cycling, is changing, too. Why are there fewer accidents on roads after the signs, white lines, speed bumps and other ‘traffic calming’ ploys have been removed? Is it because if motorists lose the illusion that a road is safe, they tend to slow down and become more vigilant? And why do more accidents in cities occur at traffic lights than anywhere else? Because drivers and cyclists have grown so accustomed to them that they focus on the lights, not the traffic, and presume – not always correctly – that everyone else will follow the rules?

Some of the most productive responses to this problem originated in the work of the late Dutch traffic engineer, Hans Monderman, during the 1980s and ’90s. Convinced that encouraging drivers to use common sense and intelligence would make roads safer than arsenals of traffic controls, Monderman applied his experience as a civic engineer and accident investigator to design what he called ‘naked streets’ bereft of controls. His experiments in the Netherlands succeeded in reducing speeding, congestion and accidents, and have since been re-invented with similar results in the design of new ‘naked streets’, such as Exhibition Road in London’s South Kensington. (Confession: I am so befuddled by the dearth of controls there that I drive much more cautiously than usual.)

Empowering individuals to reclaim control may be an efficient design strategy for road safety (if only for the time being), but not when it comes to encouraging us to engage with the latest wave of transformative technologies. Among the innovations we are already using, or expect to use soon, are: the driverless cars being tested by Audi, Google, Tesla and others; virtual- and augmented-reality headsets; increasingly powerful surveillance drones and interconnected internet-of-things devices; and the 5G wireless networks, which are scheduled to be introduced in South Korea in time for the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics and in Japan for the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics.

Computing will change, too. So far, advances in this field have been driven by increases in processing power, but the focus will increasingly be on designing smarter software, such as deep-learning programs that use artificial intelligence to emulate the idiosyncrasies of the human brain. An example is AlphaGo, which was designed by the British software developers DeepMind to play the board game Go; it recently defeated Lee Sedoi, who is regarded as the world’s greatest human Go player. Deep learning already helps computers to recognize faces and voices, translate between languages and predict how individuals will respond to different forms of internet content. It will doubtless become more effective at all of those things over time.

New types of computers will use quantum mechanics to make faster calculations, and highly sophisticated neuromorphic technology, which will be modelled on the neurons in animals’ brains. Specialist computer chips will be designed to fulfil specific functions. These chips should help computers to become more refined and precise, as will greater connectivity, fuelled by the growth of cloud computing.

The prognosis for these innovations is unclear. Some may give us greater control by creating more choices, such as being able to live in remote places without worrying about access to health care, because we can use internet-of-things diagnostic devices to assess medical conditions and relay the data for analysis at specialist clinics. Yet other technologies seem certain to result in our relinquishing control over huge chunks of our lives.

Take one innovation whose implementation is imminent: driverless cars. How will we perceive them? As liberating us from the drudgery of being trapped in congestion? Or denying us the joy of driving at speed on an open road? Will we think of them as saving us from the risk of accidents caused by drunk, careless or crazy road users? Or as exposing us to the threat of their being hijacked by terrorists as remote-controlled explosive devices?

Empowering individuals to claim control may be an effective design strategy for road safety, but not when it comes to encouraging us to engage with the latest technologies.

The possible dangers of abdicating control of moving vehicles are so grave that the old, paternalistic design strategies are clearly unfit for purpose. The ideal scenario would have been for design to play an elemental role in the development of driverless cars from the earliest stage to ensure that the possible risks and rewards are identified and assessed correctly, in order to defuse the former and enhance the latter. The same applies to the design of every other element of driverless traffic systems, from the roads to new safety measures for pedestrians.

Similarly comprehensive design exercises will be necessary to make us feel confident about surrendering control to other technologies. Will surveillance drones help to make us safer by anticipating and preventing terrorist attacks and other crimes? Or will they represent yet another threat to our privacy and liberty? Will internet-of-things devices, like digital home-management systems, liberate us from mundane tasks? Or will they expose us to greater likelihood of identity theft? Will we ever feel confident enough to trust artificial intelligence to make critical judgments on our behalf when it comes to urgent personal matters, such as our health? The scale of risk has changed dramatically: from the dysfunctional garage doors in Mon Oncle to the dystopian spectre of a near-omnipotent computer turning against us, as HAL 9000 did in Stanley Kubrick’s film, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). HAL went rogue with devastating consequences after using artificial intelligence to lip-read a conversation in which two astronauts discussed curbing its power.

These concerns are heightened by the implications of the concentration of ownership of key technologies among a few, gigantic companies. It has taken a quarter of a century for the web to morph from Tim Berners-Lee’s vision of a truly democratic system to which everyone has equal access – from a corporate colossus to a six-year-old child – into an increasingly opaque phenomenon of which only 20 percent is freely accessible with the rest sealed behind the algorithmic walls of Facebook or commandeered by the ‘dark web’. The ownership of the relatively new cloud data-storage technologies – which will fuel the growth of connectivity – is already dominated by just six companies: Amazon, Google and Microsoft from the US; and Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent from China.

Daunting though these problems are, they also present opportunities to demonstrate design’s potential to address complex issues by forging collaborations with other specialisms at a time when progressive designers are committed to wrestling with those challenges and to working more eclectically and inclusively. Anyone who doubts the wisdom of immersing design in the development of new technologies from the outset should remember the controversy two years ago when a US anti-gun control group posted the design template for a 3D-printed gun online. The group’s objective was to demonstrate the supposed futility of imposing legal restrictions on gun ownership, but it unwittingly provided a cautionary tale of the danger posed by sloppily designed technologies, whose consequences have not been fully considered – just as Kubrick did with HAL.