‘Radical Software’ Rewrites Women’s Role in Digital Art

At Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, an expansive group show amends the historiography of media art by including some of its neglected female pioneers

At Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, an expansive group show amends the historiography of media art by including some of its neglected female pioneers

Large panels filled with pages of zestfully handwritten notations set the tone for ‘Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing, 1960–91’ at Kunsthalle Wien. Covering much of the ground-floor wall space, Hanne Darboven’s Ein Jahrhundert ABC (One Century ABC, 1970–71), in which the artist sought to mark the passage of time using her own unique code, deftly connecting the renaissance origin of the term ‘computer’ – a person employed to calculate planetary positions for astronomers – to 20th-century artistic practices.

Presenting more than 100 works from 50 artists grouped into five sections, the self-described ‘principally analogue exhibition about digital art’ is a mammoth project that aims to amend the historiography of media art by including some of its neglected female pioneers. It comes on the heels of a wave of similar efforts in recent years, most prominently ‘The Milk of Dreams’, Cecilia Alemani’s 2022 Venice Biennale, as well as a renewed interest in publications like Sadie Plant’s Zeros + Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (1997), which inspired the exhibition’s curator, Michelle Cotton, artistic director of Kunsthalle Wien.

Fed up with shows about media art repeatedly exhibiting the same handful of well-known names, such as Vera Molnár – here represented for instance by the small notational drawing Lettre à ma mère (Letter to my Mother, 1988) – Cotton set out to put a wider selection of female voices on the map. And, while many of the participating artists eschew the feminist label in interviews featured in the exhibition catalogue, the all-female show was conceived as a decidedly feminist corrective gesture.

Cotton’s stated aims for ‘Radical Software’, as outlined in the exhibition literature, are relatively modest: ‘[to] counter conventional narratives on art and technology by focusing entirely on female figures’. Yet, the format of the survey exhibition renders visible the show’s shortcomings – most obviously its implicit claim to completeness. Following the exhibition’s inaugural outing at Mudam in Luxembourg last year, critics were swift to point out some of these deficits: Emily McDermott noted in ArtReview that the show would have profited from situating its female protagonists within the larger historical context, juxtaposing them with their male colleagues. In a piece for Art in America, Lua Vollaard pointed to the lack of diversity, observing that the list boasted ‘more artists named Barbara […] than artists based in the Global South’.

Indeed, the exhibition would have benefitted from addressing these absences ahead of its second iteration, particularly since Cotton is not unaware of them: ‘Of course, the minute you open such an exhibition, you discover other artists that should be in it,’ she told me. But she also seems conscious that, in order to appeal to a broad public, art must be framed in attractive, digestible terms for communication’s sake – mirrored in the exhibition materials peppered with mentions of ‘firsts’. Despite this, however, ‘Radical Software’ is, in many instances, nothing short of delightful – precisely because there is a lot to discover that is rarely, if ever, shown in Vienna.

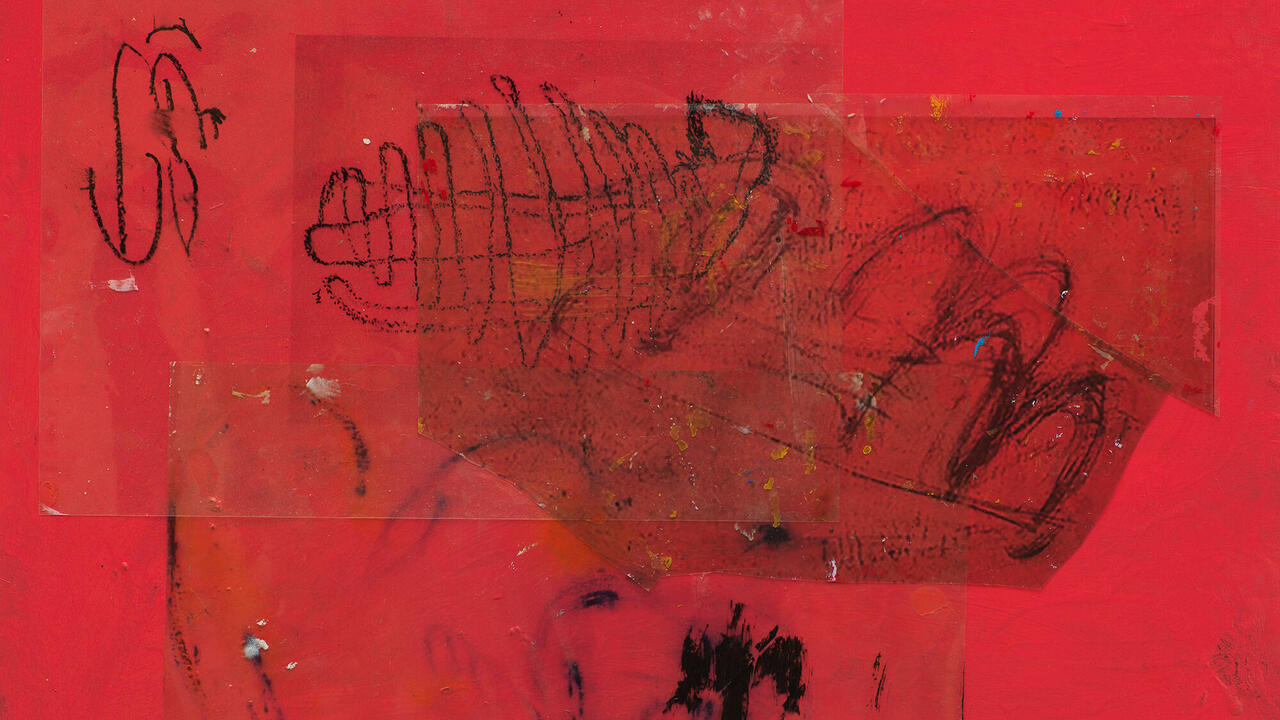

With Darboven as a starting point, the first section, ‘Zeros and Ones’, unfolds largely on paper, tracing the connections of language, code and imagery. The shapes of Homecomputer Graphics (1982) by Lily Greenham, a little-known member of the Wiener Gruppe, alongside Inge Borchardt’s Untitled (Serie C) (1966) and Joan Truckenbrod’s Untitled (1975) read like variations on the same geometric theme. Elsewhere, Bia Davou turns language into code by rendering the verses of Homer’s Odyssey (8th century BCE) into an abstract alphabet, embroidered onto her swooping, room-high sculpture Sail – Odyssey (1982). As the windowless space evokes a sanitized computer lab, two machines potter away in its midst: Alison Knowles’s The House of Dust (1967), a dot matrix printer programmed to steadily generate and print a poem, and Liliane Lijn’s small, steel-drum poem-machine, Man Is Naked (1965), slowly spinning on its axis. In one of the few performance-based works in the show, Barbara T. Smith’s light-hearted Outside Chance (1975) documents the artist dropping 3,000 printouts of computer-generated, unique snowflakes from the window of her Las Vegas hotel room.

Upstairs, on the domed second floor, the atmosphere is diametrically opposed: dimmed lights, rows of screens and clashing sounds are reminiscent of crammed server rooms. This visual cue has been picked up by Cotton in the stylish white shelving designed to loosely subdivide the large space. The ‘Software’ section draws on the relationship between the jacquard loom and computers, juxtaposing Charlotte Johannesson’s digitally woven tapestries like I’m No Angel (1972–73/2017) with Beryl Korot’s installation Text and Commentary (1976–77), which combines videos of her ‘playing’ the loom with hands and feet, meticulous manual pattern drawings and her finished weavings.

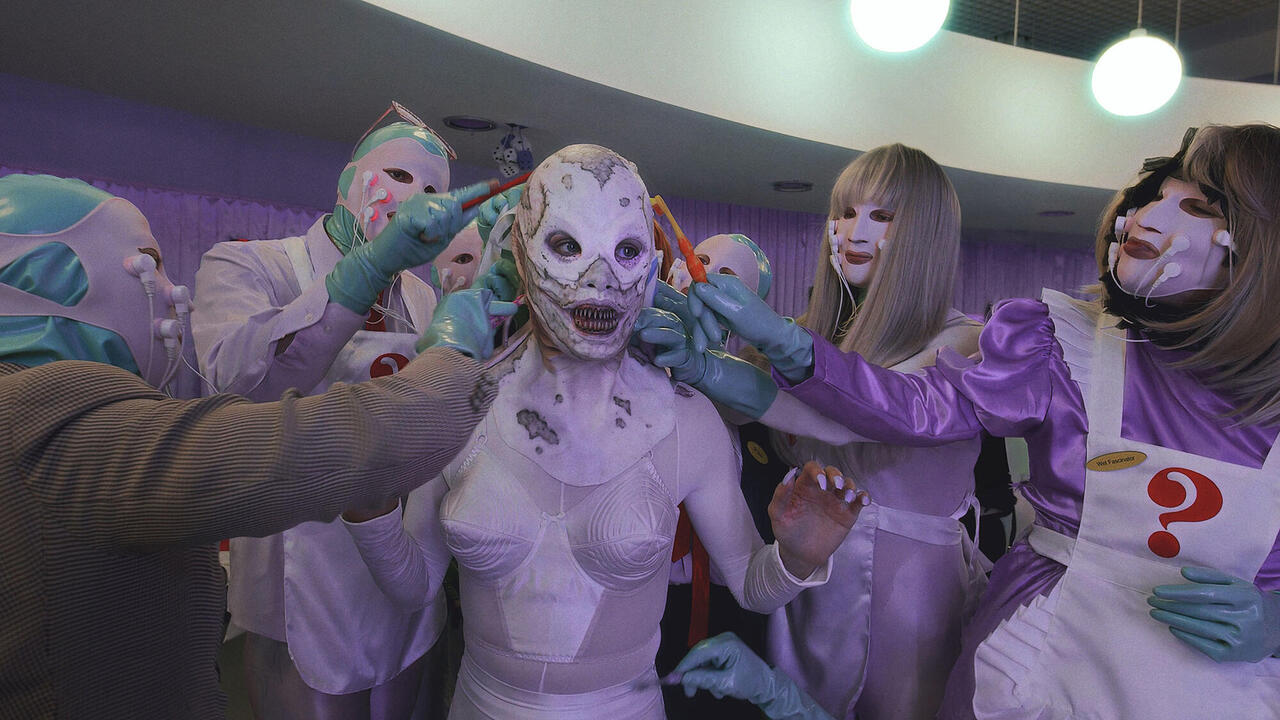

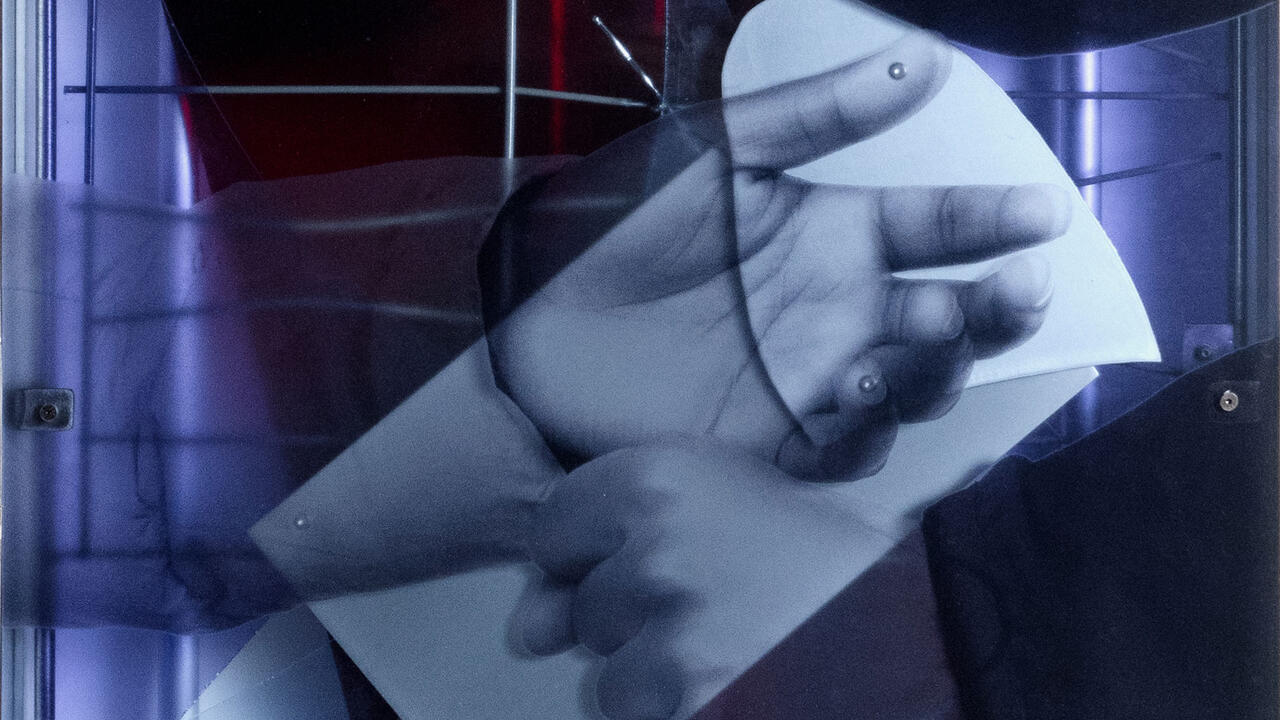

In contrast, the Pacman-like aesthetic of some early experiments from the ‘Home Computing’ section, like Samia Halaby’s coded kinetic paintings (Fold 2, 1988), seems dated. Works in the ‘Hardware’ section, however, which take computer parts as their subject, have a more timeless appeal. Katalin Ladik’s Genesis (1975), for instance, features evocative gelatin silver prints of microchips, each accompanied by one of her looping vocal performances via headphones. Similarly exquisite are some of the works in the section ‘I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess’, which focuses on the female body. Among these are Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven’s animated film Message (1988), based on early A.I. drawings, and Irma Hünerfauth’s fragile, humanoid metal sculpture, the whimsically grotesque Augen und Glocke (Eyes and Bell, c.1970).

Here, on the large upper floor, the show could have used tighter editing: it is easy to feel lost in the sheer mass of artworks, with minimal wall texts denoting sections or giving contextual information about the artists. There is so much to take in; so many questions arise and stay unanswered – not just regarding these women’s unaccounted for male colleagues but about the wider art scenes of the time, the aesthetic and political reception of the works. Each of the sections could have been a fully-fledged exhibition and, just as I sometimes found myself wishing for more, I also found myself wishing for less on occasion.

While Cotton has taken care to include a few local Austrian artists, such as VALIE EXPORT, there seemed to be some missed opportunities for more nuanced points of contact. Shaped by the rich textile heritage of the Wiener Werkstätte, Viennese artists like Hildegard Absalon, whose montage-style tapestry Self-Portrait as Penelope (1982) offers media reflection, would not be out of place.

Yet, while ‘Radical Software’ may leave some things to be desired, its merits should also be considered within the Viennese artistic landscape. Given that a survey of this size is unusual and no small feat for a kunsthalle, it’s worth reflecting that – in the light of large-scale institutions hosting solo shows by contemporary artists, such as Adam Pendleton at Mumok, or so-called blockbuster exhibitions, as seen at Albertina, which are big on names and sensationalizing PR but small on careful curatorial and art-historical framing – ‘Radical Software’ does some much-needed educational heavy-lifting.

In the patriarchal climate of Austria – where the right-wing freedom party is the strongest political force, success is increasingly measured in revenue numbers and feminist initiatives suffer budget cuts – centring the work of women artists is still more controversial than it should be. Ultimately, ‘Radical Software’ not only tells a story of early computational art in Europe and North America but highlights the social conditions of operating as a woman artist within patriarchal structures and stereotypes. Alas, here, the medium is the message.

‘Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991’ is on view at Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, until 25 May

Main image: Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven, Message, 1988, ‘Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991’ , 2025, installation view. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: kunst-dokumentation.com and © Bildrecht, Wien 2025