On Display

Elad Lassry makes sculptures that, in his words, ‘happen to be photographs’

Elad Lassry makes sculptures that, in his words, ‘happen to be photographs’

Mark Godfrey You graduated from the University of Southern California (USC) with an MFA in 2007. How did your practice develop during your time there?

Elad Lassry I chose USC so I could study with Sharon Lockhart, because her films were crucial for me as an undergrad, both in terms of the way she installed them and the way she dealt with the tradition of Structuralist film. There was something quite radical about her treatment of film as a medium. I also met other great artists who were teaching at USC, like Frances Stark, who didn’t make photographic-based work, but who I felt I had a lot in common with in terms of how she thinks about making art. I was quite a difficult student because I was really against making pictures, and yet I was still making them somehow. So I was, in part, tormented.

MG How did these encounters affect what you made there?

EL My thesis show was a series of 11×14-inch photographs – well, pictures, actually – and the film Zebra and Woman (2007). I worked the whole year on that show – it was a very long process. I slowly accumulated a bank of images, some of which were really problematic or nervous; others I made in response to the found images. Slowly my own work became integrated into the found images, and then all of a sudden I couldn’t separate the pictures I had found from the ones I had made: there was a new kind of library that encompassed both.

MG How did you arrive at showing those pictures in that particular size and in the coloured frames, which you have used in your work ever since?

EL As I was collecting images for my thesis show, I felt they needed to be hosted by something else, and this host structure slowly became the frame. The print size was a pseudo-system that referred to my education: 11×14 was the size of the prints I was asked to make in school. They needed to be small enough so you could put them in your bag but big enough so you could see the mistakes on the print. So that size became a sort of structure for the work. Then there was this idea of making the frame activate the photograph as a readymade. It became a predetermined host, like the fixed frame in Structuralist film, or the length of commercially available film stock.

MG What about the colours you chose for the frames? Did you hand-paint or spray-paint them yourself?

EL When I first used them, I asked the framer if he could paint them; he said he would, and that was it.

MG Did you see the colours in relation to external references, like a brand of car paint or a particular decade?

EL I don’t have a nostalgic relationship to colour. I guess this enters into how I think about the photographs, which has a lot to do with colouring the frames as well. The pictures I’m making are ones that have become objects, or picture–objects. My whole practice raises the question of whether the work’s existence is image-based or object-based, or whether it can be both. It becomes a struggle between the image and the presence or physicality of it in space.

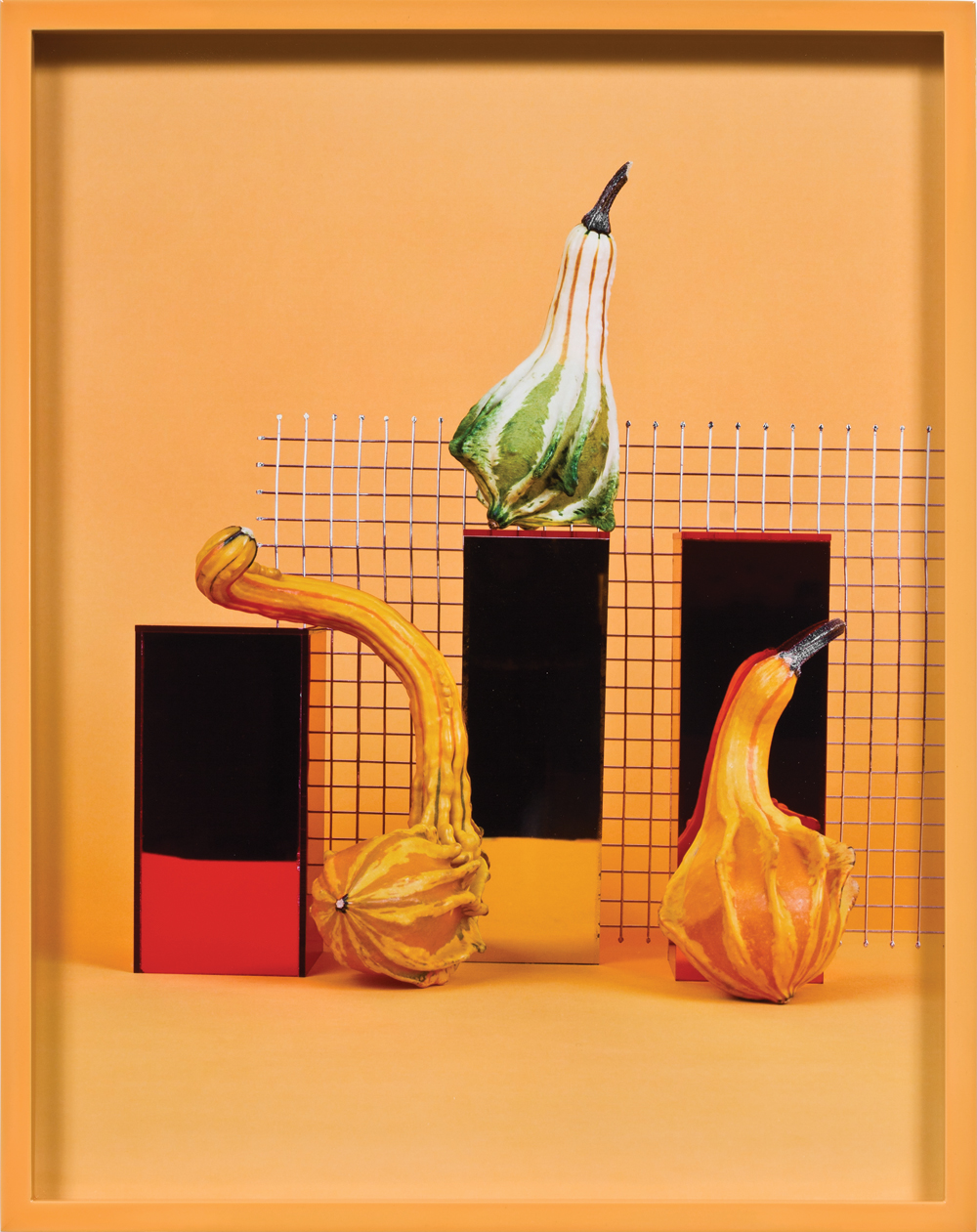

MG Let’s take Persian Cucumbers, Shuk Hakarmel (2008) as an example. On the one hand, it’s very physical and object-like because of the green frame, but also because of the sculptural situation within the image itself, in which the cucumbers are propping each other up. These are almost like sculptural objects that are on display, so when we look at the work, we see it as both an object and as a photograph of objects.

EL The word display is crucial. What I am trying to get at is basically whether the photograph can become a presence. And I think that the work does this by being both a display of an image and a shelf. It’s the question of the possible hierarchy between what’s holding the object in my arrangement and the photograph itself as an object. First, there is the relationship to the pedestal or the plinth that is supporting the object that I’m photographing. Then there is the relationship to the object itself, and how it’s read once it’s on a pedestal. And then there is the relationship to the encapsulated photograph as a display, or as another pedestal. The photograph – the finished work – for me is also a display. It’s allowed to move aside and to become a shelf or a pedestal for a viewer’s mental images, or the multiplicity or ‘ghosting’ that is within one picture – this flickering of these other mental images. All of a sudden, oranges could be apples or lipstick could be mascara.

MG Because you present the objects in terms of the language of display, they necessarily make the viewer conscious – almost self-conscious – of the act of looking. Because the thing in the photograph is so evidently saying, ‘Look at me,’ the viewer is left thinking, ‘I am looking.’ It makes us consider what it means to look at something that is asking us to look at it.

EL Everything I photograph is a display, shot straight-on in a way that flattens it out. So the surfaces of all these three-dimensional objects and their pedestals are collapsed into a flat plane that suggests a monolith or a monochrome. Similarly, when you enter the exhibition space, you first just see the lines of the works’ frames. The photographs have to open up as you walk through the space. So the image unfolds in a very analogue sense and it’s that experience that I’m interested in – making the viewer re-experience the work as an object that sneaks up on you as an image.

MG Has it been a misconception in the reception of your work that you are primarily involved with deconstructing certain kinds of images, such as the Modernist still life?

EL No, because dismantling the multiple traditions and histories of the image has been a necessary starting point in my work. Yet it is not necessarily a final destination. Deconstruction has not been satisfying to me, but it has been stimulating. It’s like the misunderstanding of Postmodernism: it never arrived to demolish the modern notion; it’s a chapter within Modernism.

Recently, I’ve been photographing fruits as ‘flipped’ still lifes; I photograph the fruits on a table, looking directly at them with a 4×5-inch camera, as if in the tradition of an Irving Penn still life. But they are actually planked between two Plexiglas sheets. This technique leads to a very strange photographic space; on one hand it references the digital scan because the objects are placed on a transparent surface; on the other hand, the physical space of the two Plexiglas sheets lit by strobe lights allows a range of shadows that recalls the Modernist tradition of still life. In my studio practice, I don’t consider histories in a linear way. I’m trying to think about the status of the picture – of all pictures. So the Modernist photograph sits side by side with all the other material I’m looking at. It is part of a vocabulary. I’m not interested in re-investigating Modernist photography, just as I’m not interested in commenting on advertising. That’s not what my work is about.

MG But do you think you are analyzing the way in which advertising photography works?

EL Advertising is part of a vocabulary. I’m interested in the images that circulate within our culture, and advertising is a massive component of what’s in circulation. Yet I spend as much time with books and images that have been pulled out of circulation. My investigation is into the condition of the picture. I am interested in the potential perceptual experiences within a set of cultural systems – going back and forth between knowledge and experience, and the points where the two overlap. I’d like people to look at the work as an accumulating archive – an archive that is full of contradictions and disturbances of a made-up system, within a more historicized meta-system.

MG You’ve used the word ‘nervous’ to describe your photographs. What do you mean by this?

EL I don’t try to make photographs. I don’t think of myself as a photographer. I think I’m making sculptures that happen to be photographs. The nervousness I’m talking about is not exclusively photographic; I’m only using photography as a means to an end. A nervous picture is one that makes your faculties fail, when your comfort about having visual information, or about knowing the world, is somehow shaken. It’s the moment when an image tells you: ‘I’m also just a file,’ or, ‘I’m just pixels.’ There are moments in my work, for instance in the black and white photographs that I frame in walnut, when the photograph’s singularity almost takes over, when you think: ‘Oh, this is – this should be – considered as a photograph.’ But then you realize that it is part of a larger group of art works. The individual photograph becomes a disruption within the larger system I’ve created. With each strategy that I apply, at some point you’ll find a failure in one aspect of it.

MG So you’re saying that the closer you get to making something which appears to be a photograph, the more misunderstandings there will be that what you’re making is merely a photograph?

EL What I encounter is a resistance within the photographic medium to consider the art experience – by which I mean that if, as an artist, you use photographs, people are much less open to considering photography as a philosophical condition than if you use other media. When I install a show, I treat the works as objects that eventually reveal themselves as images. That’s why I keep looking at my show from the side, because I want to see these flickering lines of colours and then be able to be surprised by them opening up into these problematic pictures. I don’t make art archetypes. I don’t make symbolic photographs. I don’t make photos that stand for a code. I’m interested in the image opening up as this condition that is between a picture and an object.

MG Your show at White Cube in London raises new questions around this aspect of your practice: it includes wall-mounted objects, some cabinet-like, with the same dimensions as the framed photographs. You have also created apertures in the main walls of the gallery, again sized to the proportions of the frames. For me, the installation made the photographs all the more strange, because some appeared to be doubly framed, and I lost the sense of the depth of the gallery.

EL I was thinking of the various ways in which perceptual experience takes place. In a way, I thought this exhibition was an occasion to challenge or even dismiss the vocabulary of the ‘units’ I had been putting out into the world. This installation works against them; it establishes another lens. If our perception ends in the object, the openings in the space offer the viewer various relationships to the object’s location. As you walk through the show, I’d like you to ask yourself whether or not the objects might also be approaching you. Then the question of an object that is also an image becomes more of a problem. It’s the notion that my pictures are not enclosed in a singular perspective, or a singular institution.

MG When you put a group of photographs together in a space, though there are links between them, ultimately there is always something that disrupts the unity of the system. What do you think has changed between your generation – which seems to feel there is an impossibility of creating a coherent group of photographs with links among all of them – and, for instance, the older generation of photographers that includes Christopher Williams, who want to create connections among their photographs, even if these are connections that viewers might not at first recognize?

EL Links are funny to me; I never had an experience of being linked, even as a self. Links are a seratonin-based fabrication. My photographs are orphaned: you don’t know where their subject or objects come from. Williams’s photographs ask you to analyze or reflect on existing structures and economies. His is a very analytical practice. As far as my practice goes, I don’t allow the pictures to be thought of as photographic. Someone like Haim Steinbach, who is one of my favourite contemporary artists, has much more to do with my work, in the sense that he presents objects. I’m wondering how can we get to a place where we are thinking about the object again through the photograph. How is it possible to leave aside representation for a second when it already exists as a representation? What does it mean that I’m 33 and a consumer – a very aggressive consumer – of images? I think, for me, there is also such a strong divorce from the boundaries and limitations of photography. I’m not overwhelmed by the idea that photography can be conceptual. I don’t find that problematic. And I think that’s a very generational thing. I don’t find the fact that a photo can be a tool or a form of vocabulary troubling. It’s a given. I’m making work. I’m making an art work with photographs.

Elad Lassry lives in Los Angeles, USA. A solo exhibition of his work is on at White Cube, London, until 12 November. He is currently working on a solo exhibition for The Kitchen, New York, USA, which will open in 2012.