Donna Huddleston Perverts Reality With Performance

The artist’s inaugural show at Simon Lee, London, draws from the annals of cinema history – from Rainer Werner Fassbinder to Chantal Akerman

The artist’s inaugural show at Simon Lee, London, draws from the annals of cinema history – from Rainer Werner Fassbinder to Chantal Akerman

Stepping into ‘In Person’ – Donna Huddleston’s inaugural solo show at Simon Lee, London – is like entering a miniature amphitheatre starring alien divas and Vivienne Westwood-styled punkettes. Often emerging from rainbow spears of Caran d’Ache pencil, the Irish-Australian artist’s works pervert reality with performance. Yet, where earlier drawings – such as The Warriors (2015) – depicted Earth girls in fairy-tale sportswear, here her work has respawned to resemble a screenplay on Venus.

Personal Development (2021), for instance, comprises layered compositions. A character poses in front of dirty Venetian blinds. With her light-green skin and darker green lips, she looks like a leaf. Below her, a pink flower opens. The piece resembles a Jim Nutt drawing after immaculate plastic surgery.

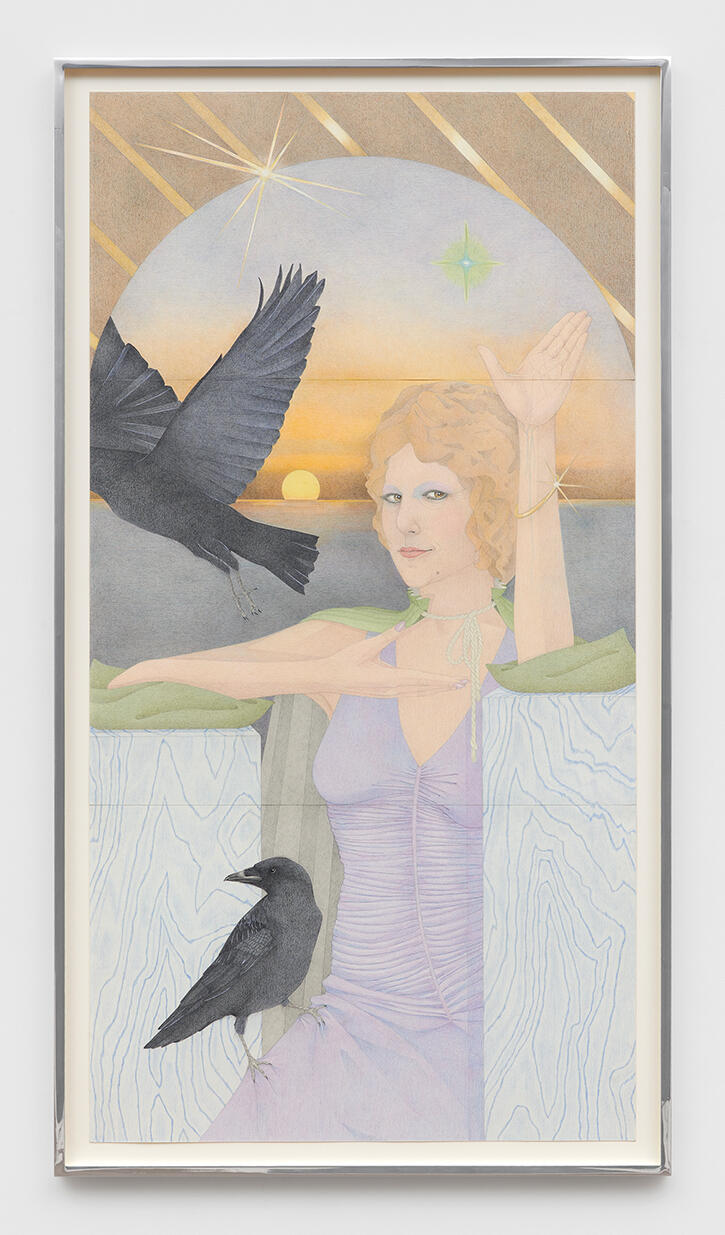

Huddleston is a philosopher of film. Her attention to doubling – through character, piano-key motifs and split composition – recalls Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Despair (1978). Based on the novel by Vladimir Nabokov, Fassbinder reimagines the protagonist – Hermann Hermann – as Eurotrash amid silent rain. Hermann’s infinite reflection torments him: he sees his double everywhere. In their compact mirrors, Huddleston’s characters also reflect Fassbinder’s doomed actors. For example, The Stand In (2021) pictures a star in blue eyeshadow with ultrathin, sword-like eyebrows. Her hair is wig-textured: equal parts The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) and a kitten. While some first-person shows may float into solipsism, Huddleston never breaks her glamorous character.

Silverpoints coil into a Hollywood Shady Lady (2021). She wears a white blouse with the texture of a bubble. Ivy twists around her. Huddleston’s formal spareness involves her screenplay phenomenology. For instance, Time Passed (2022) resembles the setting and tone of Chantal Akerman’s film Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975). With the vacant stare of Akerman’s compressed title character, a figure rests on a bed and holds a cigarette burning white. Akerman’s film is a planet where a spoon can feel like Patrick Bateman’s chainsaw in American Psycho (2000) – which is to say that, despite materializing from wisps of smoke ‘pencil’, Huddleston’s characters are opaque and resilient.

Brighter (2021), however, is as baroque pop as The Beach Boy’s song ‘Surf’s Up’ (1971). A solar-orange disk inflames a comic-book caped protagonist. The stratosphere appears studded in weird, light-green and gold stars. Spindly blue veins poke from her raised arm. She could be an unusually hieratic extra in the television show The Sopranos (1999–2007) or the anime-eyed Mia Farrow in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Meanwhile, Capricorn One (2021) contains a yellow figure with an ash-blonde ponytail. She has a bright cupid’s bow and silvery eyeballs like water in nebulae.

Akerman famously told a reporter in 1982: ‘The more particular I am, the more I address the general.’ ‘In Person’ emanates a related sensibility. Huddleston spins her own memories (and face) into something totally extra-terrestrial, while raising wider questions: how do artists approach self-performance in the age of social media, when apps such as TikTok and Instagram appear to be Narcissus’s plasma lake? How do artists express – not moralize – their inner depth while taming the fat, relentless ego? Isn’t vanity the enemy of good art?

Donna Huddleston, ‘In Person’ is at Simon Lee, London, until February 26

Main image: Donna Huddleston, The Stand In (detail), 2021, caran d’ache on paper, 106 × 78 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Simon Lee Gallery. © Donna Huddleston.