‘Dowsing’ Refuses to Take Sides

At Layr, Vienna, a group exhibition reminds viewers of the culture-crossing and nonconformist possibilities of artworks

At Layr, Vienna, a group exhibition reminds viewers of the culture-crossing and nonconformist possibilities of artworks

Widely regarded as nonsense by the scientific community, dowsing – divining the location of water and minerals in the earth with a stick – is, like astrology and the tarot, nonetheless still commonly practiced. In titling an exhibition after this type of occultism, curator Nick Irvin suggests a portrait of contemporary culture through the fringe beliefs of society at large. That these outer limits have moved closer to our daily centres, in a society both divided and reactionary, is reflected in a broad artist list containing known young quantities (Whitney Claflin, Jeffrey Joyal, SoiL Thornton), artists finding attention later in life (Gene Beery, Matthias Groebel) and multi-media practitioners, such as Lee Scratch Perry, whose work sits between serious respect in one cultural realm and another.

Courtesy: suns.works and The Visual Estate of Lee Scratch Perry; photograph: kunst-dokumentationen.com

The installation echoes the heterogeneous nature of the assembled works. Julie Becker’s photograph of crepuscular rays reflecting off a television, Poltergeist (1999), greets viewers as they enter the space. Much wider than the width of the wall it hangs on, the piece floats confrontationally and unconventionally in the gallery space, like the cinematic ghosts its imagery and title quote. Beery’s Where Is the Best of Me? (1987–94), a portrait of Ronald Reagan’s jovial floating head, meanwhile, is tucked around a corner near where the gallery guest book and exhibition literature rest. The painted caption, ‘The Fortieth President of the United States of America!’, creates an ambiguity between celebration and ironic takedown, which seems intended to be decided publicly before the eyes of a gallery attendant. Some of the most conventionally installed aspects – a group of five glass-topped vitrines placed throughout the gallery – turn out not to be art at all. In each is ephemera collected by Donna Kossy of Kooks Archive, a writer who published a zine related to the distribution of fringe beliefs three decades ago. Pamphlets and posters about UFOs, the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement and evangelical apocalypticism, which echo the language and look of punk rock and the proselytizing labels of Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps, are presented as equals to the art by which they are surrounded.

These themes are echoed directly in Ben Sakoguchi’s grid of portrait paintings-cum-fictionalized fruit labels. Evildoers Brand (2002), for instance, depicts Mohamed Atta, leader of the 9/11 attacks, alongside Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh and attempted ‘shoe-bomber’ Richard Reid above the slogan ‘Uniformly Good’ – since McVeigh and Reid are pictured in orange jump suits it becomes a dad joke with dark roots. Elsewhere, everyone from the leader of the Heaven’s Gate cult to Nazi war criminal Hermann Göring gain a similarly black comedic commercial treatment. The works’ small scales and illustrational style – the kind associated with the promotion of California oranges – sits on the edge of folk art, creating a creeping uncertainty as to whether these are clever conceptual gestures or the work of an obsessive and radical outsider.

This entwining of the effects – both dangerous and benign – of fringe thought and action on society makes a kind of sense within the structures of art. What better platform to explore the uncomfortable mix of truths and lies driving us all along? Each of the works Irvin assembles at Layr sits on a spectrum of equivocacy, refusing to take sides definitively at a divisive moment in global society that witnesses both rising fascism and liberal McCarthyism, reminding viewers of the culture-crossing abilities and nonconformist possibilities of artworks themselves. In this loose portrait of thought at the edges of society, we’re reminded of both the oddness of, and the power granted by, art as divination. Nothing is conclusive; its openness is the point.

‘Dowsing’ is on view at Layr, Vienna, until 14 October.

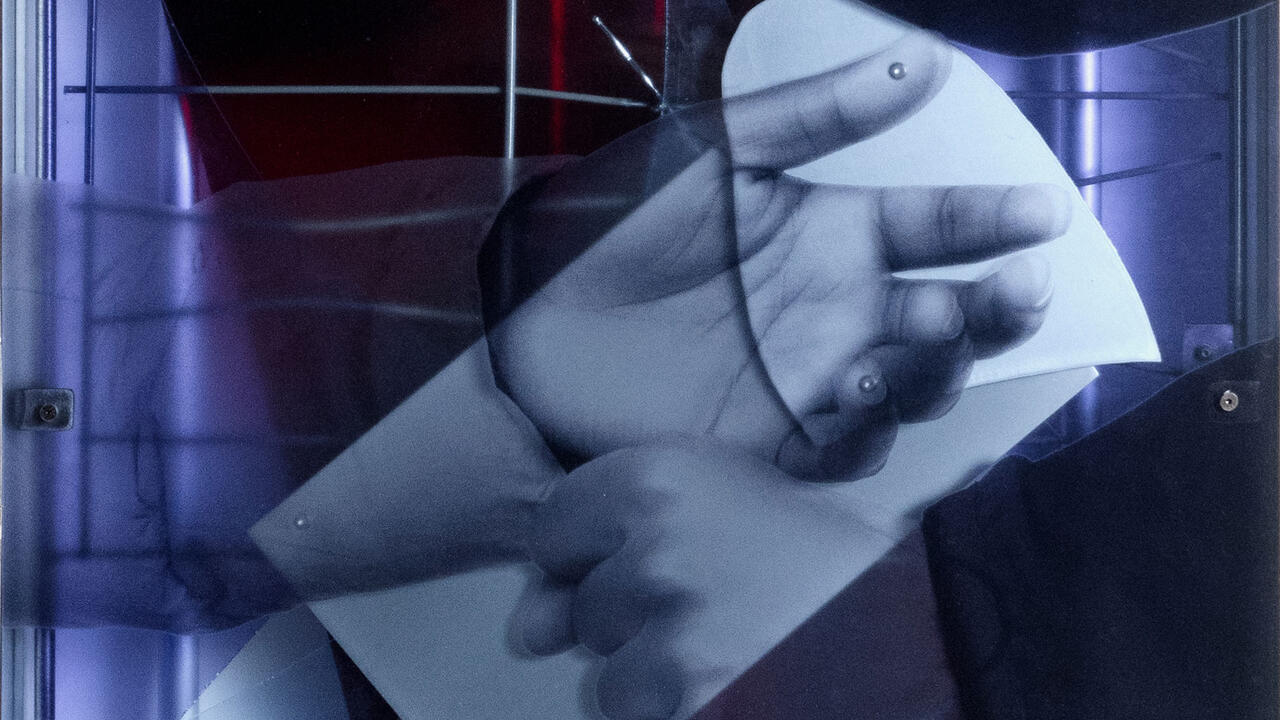

Main image:Whitney Claflin, Writer’s Block, 2023, vinyl on plexiglass, stretch foil; 4 panels, each 1.2 × 1.2 m. Courtesy: the artist and DREI, Cologne; Photograph: kunst-dokumentationen.com