The Fight for Hong Kong Is Not Over

After the announced withdrawal of the controversial extradition bill, artists and cultural workers are amongst those keeping the protest movement alive

After the announced withdrawal of the controversial extradition bill, artists and cultural workers are amongst those keeping the protest movement alive

Three years ago, when I moved to Hong Kong, the city was still dealing with the failure of the 2014 Umbrella Revolution – widespread sit-in pro-democracy protests that ended with court orders and hundreds of arrests, but no concessions on the part of the legislature. Living in the spectre of a dream that has not come to pass is massively depressing. I had been part of the student protests in Montreal in 2012; in solidarity, the artist Firenze Lai gifted me a small print engraving that showed a scratchy figure lying in the middle of the road. She said, ‘[the] Umbrella Revolution was the first time that many of us lay in the middle of the road, looking up at the same sky. Up until that moment, we didn’t think this feeling was possible.’

And then it happened again. On 9 June, more than a million people marched in protest at a bill proposed by Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive. If passed, the legislation would have allowed the detention and extradition of people wanted in countries with which Hong Kong has no formal extradition treaty. These included mainland China, whose courts are controlled by the Communist Party. On 16 June, I made my way down to the government buildings at Admiralty and stayed all day. Before leaving, I lay in the middle of Harcourt Road to be with everyone else. As the protests have grown, the alternate systems of care that have sprung up in place of the government lend credence to the resilience of those on the street. The frontline is lined with volunteer medics and social workers. People pass out water and snacks. If I fell, I’m certain I would be caught before hitting the pavement.

On 4 September, after three months of protest, Lam announced that the extradition bill would be officially withdrawn. However, demonstrations have now escalated to a greater set of demands, which have still not been met. These include: the retraction of the government’s characterization of the protests as ‘riots’, an independent inquiry into police actions, amnesty for all arrested in relation to the protests and the implementation of universal suffrage in electing Hong Kong's Chief Executive. The movement feels like a last stand: if this battle is lost, we will lose Hong Kong forever.

Artists and art workers have followed the decentralized nature of the protests. Unlike during the Umbrella Revolution, where installations and artworks were created at many occupied sites, the current protests have embraced impermanence. So-called Lennon Walls have sprung up throughout the city in overpasses, underpasses and walkways along with graffiti of hopes and desires; posters and animations are spread through Telegram, WhatsApp and LIHKG (Hong Kong’s Reddit).

An internal reflection is being undertaken within artistic communities about what it means to practice as an artist or art worker in the midst of this crisis in Hong Kong. As artist and activist Kacey Wong put it to me: in larger government affiliated institutions, the ‘authority of the curatorial decision has been amputated’. Art workers from institutions such as M+, the Leisure and Cultural Services Department and Tai Kwun (where I work as associate curator of public programmes) have anonymously voiced their support through striking, putting their bodies on the line at actions and making their own statements.

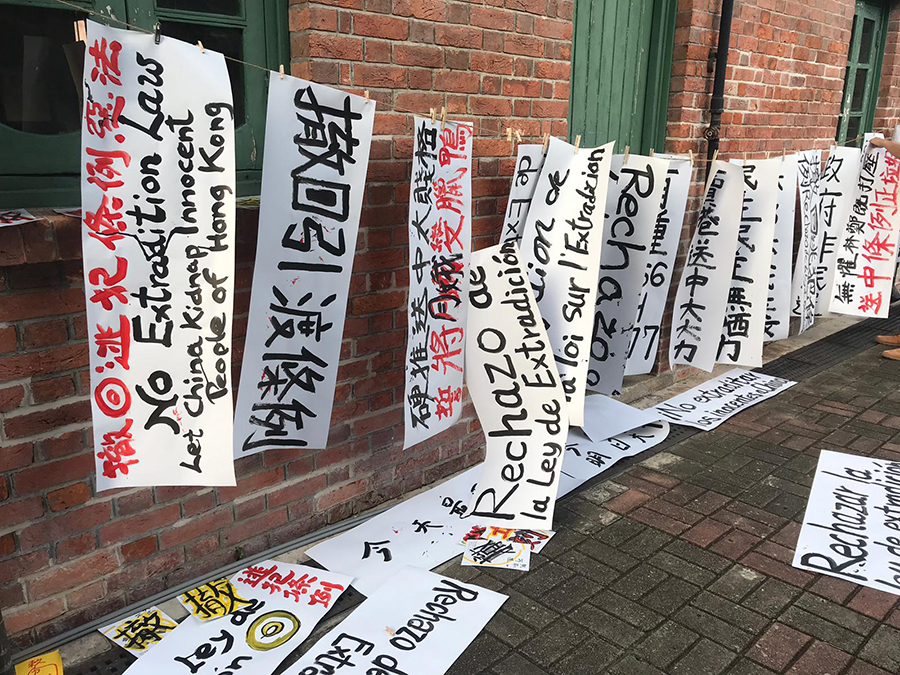

Wong noted that contemporary art by its definition should be relevant, ‘if not [a proposition for] the future, at least [a reflection of] the now’. The Hong Kong Artist Union (HKAU), which claims to have up to 600 members, has been active in the protests in bringing people together to make posters and galvanizing the voices of cultural workers. Ky Wong, an artist and spokesperson for the HKAU, has been active in organizing strike actions. A display of recent protest materials was installed by the Union at Para Site as part of the exhibition ‘Bicycle Thieves’, curated by Zhang Hanlu.

The term ‘be water’ has become the clarion call of the protests and derives from the fighting spirit of Bruce Lee, speaking to both the rapidly changing actions taken by the government as well as to the evolving tactics of the protesters. The demonstrations are remarkably self-organizing and the transmission between online discussion to offline reality is almost immediate. Graphic art takes on a meme-like quality as phrases used in government press conferences are reproduced en masse through copy culture. From the outside, it may be difficult to pinpoint the reality of Hong Kong on the ground now. A pro-democracy movement with a very specific historicity, the struggle for freedom and self-determination is being fought on the premise that this may be the last time these rights can be exercised in this territory. On 4 August, art critic Anthony Leung Po Shan published the English version of a letter about the frontline, urging friends and colleagues to join a general strike: ‘There have been already many Hong Kongers on the frontline fighting for the future of the city […] Strike is our only non-violent way to pressure the government now.’

Clara Cheung, co-collective member of C&G Artpartment, art director of the charity Art Together, and art educator, has joined a group of 11 in the Wan Chai area of Hong Kong in a serious consideration to run for district council. (Usually, people declare their official running in October as the election will take place on 24 November of this year.) Spearheaded by Clarisse Yeung – who already holds a seat in the Tai Hang section of Wan Chai District and worked on artist Chow Chun Fai’s unsuccessful bid for the Legislative Council in 2012 – the group of 11 hopefuls includes three with art backgrounds: Cheung, Yeung and Susi Law, the cultural engineer of ACO Art Space and graduate from Baptist University’s Academy of Visual Arts.

The creativity of the protest movement has far outgrown all the existing artistic institutions in Hong Kong. Artist and activist Sampson Wong noted that artistic actions – from a teargas canister sculpture that appeared on an overpass in the Tai Po area to the laser light show party in Tsim Sha Tsui on 7 August in response to the arrest of the head of Baptist University’s students’ union Keith Fong Chung-yin, arrested on the grounds of possessing 10 laser pointers used to obscure photo-takers who could identity protesters. It begs the question: why have our institutions failed to incubate this creative spirit before? Is ‘relevance’ about direct, socially engaged actions, or should we also consider what’s left of the autonomy of art itself as a crucial form of civil liberty to be preserved?

Critic Yang Yeung puts it beautifully in a letter she released on Facebook following the events of 12 June, which saw the first use of police brutality in these protests:

Dear all, who make art and make art happen,

It had happened before. It is happening again and it may well happen over and again that we are challenged to suspend what we do in art, with art, for art, and as art, to ‘join the protest’. The act of putting everything in our hands down and changing their orientation, to wrap elbows around each other and march on, is beautiful, compelling, and in critical times, urgent and necessary. I am writing this letter not to dispute that. Not at all. I am here to make the case that we don’t have to lay art down in order to protest. We can do both at the same time. In fact, we must.

It was 16 June or the day the protesters entered the Legislative Council. I stood outside with my goggles, wearing a face mask. I watched as people shone their cell phone flashlights from inside the building, hundreds in helmets and black clothing.

That was the first time the call to wear black was made: in memory of Leung Ling-Kit, who had committed suicide the day before by falling down the facade of high-end shopping mall Pacific Place in Admiralty District. He had been wearing a yellow rain jacket and unfurled a banner that read: ‘No extradition to China, total withdrawal of the extradition bill, we are not rioters, release the students and the injured, Carrie Lam step down, help Hong Kong.’ (He would be the first in what are now five people who have fallen to their death in protest).

On Monday 2 and Tuesday 3 September, returning students called a strike for the first few days of school and university. Others who attended organized peaceful demonstrations such as singing protest songs during the orientation assembly. ‘Five demands not one less,’ the slogan goes now. Be water. Keep moving and keep changing tactics. I am certain now that we won’t give up Hong Kong.