Five Non-Figurative Artists on Abstraction

Five contemporary painters, from Charline von Heyl to Tauba Auerbach, discuss the role of abstraction

Five contemporary painters, from Charline von Heyl to Tauba Auerbach, discuss the role of abstraction

What does the term ‘abstraction’ mean to non-figurative painters working today? I spoke to five artists - Tomma Abts, Tauba Auerbach, Matt Connors, Charline von Heyl and Bernd Ribbeck - all of whom make work grounded in process and materiality. There is a dissonance between the directness of their work and the fuzzier set of interests and objectives – high-minded, metaphysical and historical – that ‘abstraction’ suggests. None of these painters seem interested in spirituality as a social idea or abstraction as a historical category, but they share a real belief in the metaphysical properties of work, materials, process and practice, a kind of secular faith in the possibilities of non-objective image-making. Their desire is not for transcendence through abstraction, but for a greater embeddedness in the world through materials and work.

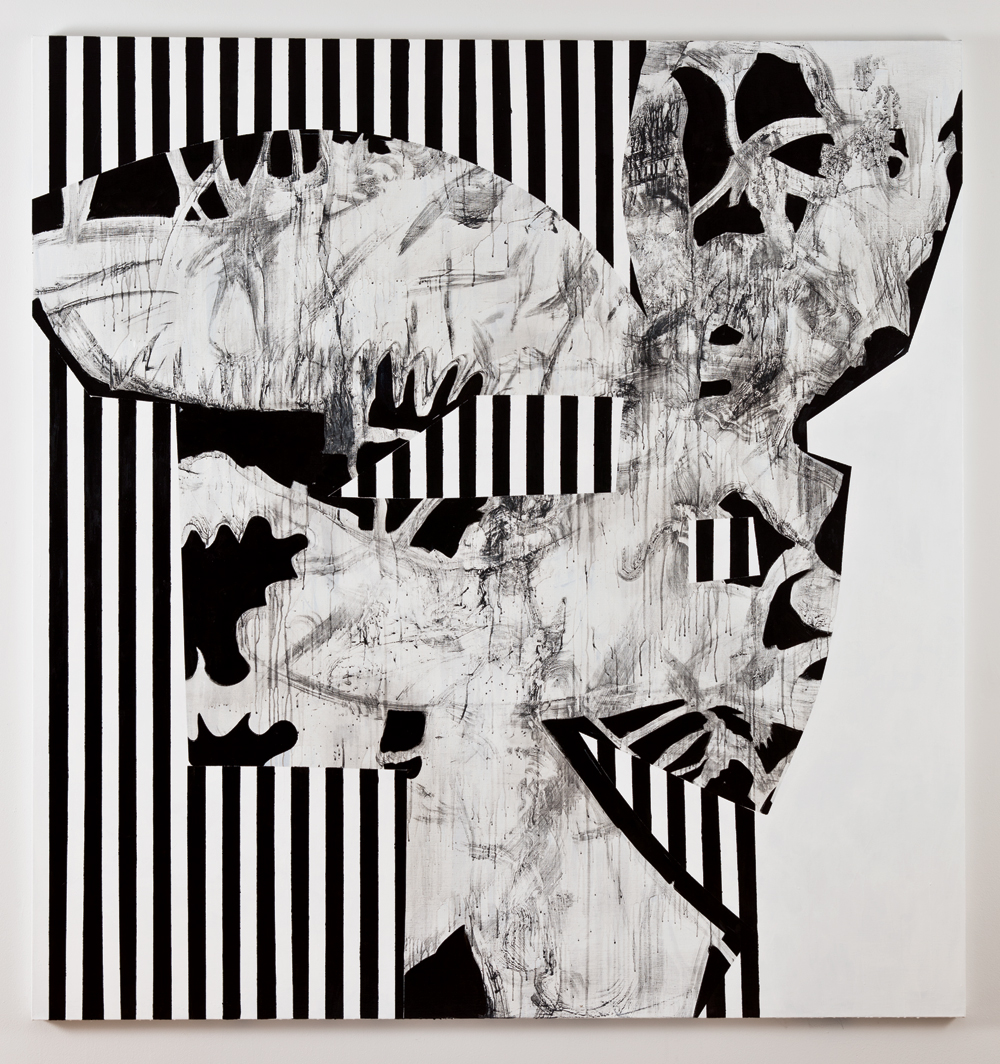

Charline von Heyl

Lives and works in New York, USA. In 2011 she had solo exhibitions at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, USA, and 1301PE, Los Angeles, USA. Her major survey show at Tate Liverpool, UK, runs until 27 May before travelling to Kunsthalle Nuremberg and Bonner Kunstverein, Germany.

Christopher Bedford You’ve said that your interest in abstraction stems from a desire to access ideas and sensations beyond the reach of language. How is that manifested in your working process?

Charline von Heyl I start playfully, according to a mood or a desire for a sensation or colour. Usually my first move will be painted over, but sometimes this first gesture is perfect and the painting is finished right there and then. Painting has a history of fooling with expectations, and in representational painting you can contemplate the moves easily: objects can be foreshortened or elongated, defying the rules of perspective; colours can be counterintuitive; visual hierarchies can be messed with. These manipulations can be aggressive, analytical or full of tenderness, but they are always obvious; they can be talked about. My moves and counter-moves are initiated by similar violations, even though it might look as if I’m breaking rules where there are none. In the end, a self-reliant new image seems to have created itself.

CB You often use ‘tasteless’ colours in dizzying combinations. How does taste relate to the moves and counter-moves you describe?

CVH I think that taste is underrated as a power. One’s formative tastes are linked to a sincere conception of beauty. They stay charged, symbolically and aesthetically, no matter how much we should (and do) ‘know better’. We think our taste is evolving, often losing a powerful link to who we are and what we can do. The ‘tasteless colours’ in my paintings are the colours I grew up with. I find no others to be so directly satisfying. I later acquired more and different tastes, but I have never really gotten rid of any. They are all part of my vocabulary now, and I enjoy juggling their contradictory agencies.

CB Do you hope that your paintings have the capacity to expand a viewer’s taste?

CVH People tell me they have gone back to see my paintings even though they didn’t get them or disliked them at first. The second time around they were ‘converted’, so I guess something does shift in their taste. Also, the paintings stand for themselves as their own weird universes, often contradicting each other aesthetically, so people look for ‘their’ paintings, choosing, rejecting or changing their minds. I think the work succeeds when it sets the viewer’s taste into motion.

Tomma Abts

Lives and works in London, UK. In 2011 she had solo exhibitions at Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Germany, and greengrassi, London. Her work is included in the group show ‘The Indiscipline of Painting’ at the Mead Gallery, Warwick Arts Centre, UK, until 10 March.

CB Over the years, some of the painters I admire most have said that their main objective is to create an image they have never seen before. I’m curious if you share that conviction and, if so, what relationship that goal might have to abstraction?

Tomma Abts I don’t know if I would call it a ‘goal’ to make something unseen, but maybe an incentive – not knowing what the outcome might be is what makes me want to start another painting. I have no plans, sketches or preconceptions when I begin, it is just decision after decision – an ongoing process of putting something onto the canvas and then editing it, then putting something down and editing it again – and in that way slowly constructing something. I don’t think that ‘unseen’ equals ‘abstract’; I think unseen has to do with the openness of the process. The making itself leads the way. The image is the manifestation of the process. I am not sure what the term abstraction means at this point. I have certainly never made a decision to be an abstract painter in the sense of having a concept I have to adhere to. I just think it gives me a lot of freedom not to have to work around representational issues, meaning that nothing is a given.

CB Forging something from nothing is a deeply romantic idea. Is romance something that exists for you when making an image and, if so, can you say how? Do you imagine the viewer having access to that sentiment?

TA ‘Romantic’ isn’t something I am afraid of or embarrassed about, but I don’t think about it or the viewer’s response. When I paint, I have to deal with the problems at hand. But I know that viewers’ responses go beyond recognizing the formal construction, or the discourse it might relate to in their heads. There is something else going on, because the painting is developed over time – while working on it I am always open to what I might do with it next, nothing is fixed. And, as we all know, ‘higher beings’ are involved!

CB Perhaps you mean that in jest, but I do think artists – often those who deal to some extent with abstraction – are becoming more forthright about the relationship of their working process to metaphysical concerns or even spirituality. What do you mean when you say ‘higher beings’?

TA I was hoping not to have to expand on that! Sigmar Polke summed up this discussion perfectly in the 1960s. Most painters have the experience that painting ‘happens’ not when you try really hard, but in the moment when you let go. Things can fall into place in a way you couldn’t have conceived of before. I don’t feel comfortable with the word ‘spirituality’ in connection with my work. It immediately evokes a notion of spiritual kitsch, and makes me think of work that takes itself too seriously in its tackling of grand themes. For me, painting is a concrete experiment that is anchored in the material I am handling. Metaphysical concerns – in the sense of examining the properties and possibilities of an object – sounds better.

Bernd Ribbeck

Lives and works in Berlin, Germany. Recent solo shows include Galerie Kamm, Berlin, and Norma Mangione Gallery, Turin, Italy (both 2010). This year he will have solo shows at Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK, and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich, Switzerland.

CB You’ve said that spirituality is central to your interest in abstraction. Can you say a little about that and also where you identify the historical origins of this interest?

Bernd Ribbeck I am interested in the work of a few artists who used spiritual channels in the creation of their work. These channels elude me, but the shape and character of their art works are unique, so I assume that the specific pathway to their genesis played a great role. Hilma af Klint’s work is seminal in this respect. She found her way to abstraction very early on through spiritual experiences. There is also the Swiss healer Emma Kunz, who used a pendulum to compose her drawings, or the Belgian miner Augustin Lesage, who began to create complex symmetrical paintings following a vision he had in the mine, according to direct instructions from ‘above’. Twentieth-century church architecture also took on shapes that affect me, as ‘bastard’ hybrids of modern rationalism and the spiritual role these buildings were meant to play.

However, my influences can also be much more profane: shapes that, although quite concrete, also convey a promise of luck. The lozenges on a roulette table, for example, or the soundscape in a casino when all of the slot machines emit high notes – to me that’s almost like the divine sound of a very terrestrial joy. The same goes for geometric shapes: they are basic forms but they are also part of the ‘high’ culture; although simple to construct, they can become complex and charged during the process of creating an image. As a painter, I only believe in what I see, but what I see also causes me to believe or at least to imagine. I’m not a religious person, but one could credit religion and spiritual practices as special methods of imagination, even if one views religion critically. One might understand religion, for instance, as a practice of the imagination.

CB Are your paintings acts of the imagination that make an effort to transcend the familiar, or are they more referential and terrestrial, like the slot machines singing in unison you describe?

BR I am not sure if I can really answer the question, because on the one hand there’s a spiritual or intellectual background that enables me to work, but on the other hand, there are the specific problems of the work itself. There’s always a difference, otherwise it wouldn’t be necessary for me to paint.

For me, the idea that my paintings could originate from another world or time gives me the freedom to move artistically. That things are transcended is a mechanism of art – there is a material, then it’s moved into another space or combined with other materials and afterwards it’s not what it was. Materiality is very important to me.

Matt Connors

Lives and works in New York, USA. In 2011 he had solo shows at Luttgenmeijer, Berlin, Germany; VeneKlasen/Werner, Berlin, and Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Germany. He will have a show with Marc Hundley at Herald St, London, UK, in April and a solo exhibition at Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles, USA, in September.

CB Of the five artists I’m talking to as part of this article, you are perhaps the least uncomfortable with the label ‘abstract painter’. Can you talk a little about that and where you identify the historical origins of your abstraction?

Matt Connors You’re right, although I don’t particularly see my own work in a purely ‘abstract’ way. My work has always had specific origin points in the real world, but I have slowly made a kind of inward progression so that materials, processes, the studio and my own actions have all started to qualify for me as origin points in and of themselves, which can amount to pure invention in some ways. I’m certainly not making a window onto a picture but I do feel like I am creating and referencing very real physical and aesthetic presences, if that makes any sense.

The historical origins of my particular abstraction could be located in or around Abstract Expressionism – sharing its studio-based approach, interiority and personal gesture – but, in truth, I think this is the least interesting point of reference for my work. In as much as there is a kind of hovering connection to the real world, artists working in abstraction directly before and after AbEx – for instance, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Morris Louis, Helen Frankenthaler, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Ryman, Paul Feeley or Kenneth Noland – seem much more like kindred spirits.

But really, work that has very little or nothing to do with an AbEx paradigm has been much more important to the development of my personal abstraction. Henri Matisse is a really foundational artist for me, as is late 1960s American and European conceptual art, certain Arte Povera artists, as well as French and German painting of the 1960s through to the ’80s – Yves Klein, Daniel Buren, Martin Barre, Olivier Mosset, Blinky Palermo, Gerhard Richter, Martin Kippenberger, Imi Knoebel, Sigmar Polke – not to mention many non-art practices, such as design, writing and music … I haven’t ever really felt or even understood the need to situate myself in any lineage, other than a sort of elective affinities grouping, which is maybe a very contemporary luxury for an artist.

CB One thing that the ‘elective affinities’ model of thinking permits is constructing a dispersed, non-linear peer group across time and media. Can you say why you view this as a ‘very contemporary luxury’?

MC Maybe it’s not so contemporary, actually. I imagine if you were to go back and ask, artists and writers have most likely always been constructing these idealized peer groups: the French nouvelle vague excavating US film noir; the New York poets’ obsession with Arthur Rimbaud and Ronald Firbank; David Hockney’s fixation on Pablo Picasso. I think it’s just something that artists do, an intrinsic part of making art.

Finding your peer group ideally would still include real-life peers, fellow artists working in the same time and place, with similar techniques and ideas. In the past, I think there were very particular and sometimes very serious stakes being played out in terms of exactly how one was situated, or situated oneself, in a very forward-moving chronological narrative, whereas now I think these coteries are obviously still being constructed, but sometimes more emphasis is placed on the fantasy football league aspect rather than the possibility of a living breathing school of artists, and a ‘forward’ movement is not taken for granted or even desired. Maybe it’s been this slow redirection of artistic inquiry from strictly forward-moving into a kind of super-branched-out, questioning rather than asserting, forward- and backward-looking activity and thought process that foregrounds the research part of it.

There can sometimes be a sort of panic or rage about originality that can make contemporary artists stop this search for peers just short of their own present-day milieu, or which could give this research an ulterior motive of sussing out some absolutely ‘of-the-moment’ originality, which I think is a real bummer.

CB That said, are there artists you identify as peers?

MC I have filled my life with other artists whose work I really love. Some of them are actual friends and some I don’t personally know but I admire their work. Witnessing people living their lives and then transforming that into their work is a really wild and very serious privilege, one that makes me constantly examine my own life and experience. I think there should be a non-pejorative word for nepotism that would mean something more like legitimate mutual appreciation.

Tauba Auerbach

Lives and works in New York, USA. She has work in the group exhibition 'Lifelike' at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, USA, which runs until 27 May and she has a solo show at Malmö Konsthall, Sweden, from 17 March to 10 June. In May she will have a solo exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

CB In a lot of your recent work, flatness and dimension co-exist, exerting a playful push and pull. While this makes me think of Clement Greenberg’s ideas and the years of dissent they’ve spawned, I know you are not much interested in theory. How would you describe your motivations as a painter?

Tauba Auerbach Theory does not motivate my work. When I have the opportunity to read, I usually read short stories or science articles. Right now I’m reading about Henri Poincaré, one of the founders of the field of topology. I only sometimes think of my work as abstract. I think it’s more ambiguous than that. Most recently, I’ve been working on woven pieces that take the image of a corner as a starting point. And I think you could make as good an argument for my ‘Fold’ paintings being representational, realistic or even trompe l’oeil, as you could for them being abstract. There is a direct, 1:1 relationship between every point on the surface of the image and that same exact point on the surface in the image. Because I spray the creased canvas directionally, the pigment acts like raking light and freezes a likeness of the contoured material onto itself. It develops like a photo as I paint. The record of that topological moment is carried forward after the material is stretched flat. Each point on the surface contains a record of itself in that previous state.

CB This brings your work into a deliberate and interesting dialogue with the mechanics of photography.

TA I suppose that, in one sense, the works I’ve made in the last few years put the mechanics of painting right on the surface, particularly in that they highlight the properties of a fabric support. But they physically come about more like Walead Beshty’s photographs do, rather than, say, how Cornelius Norbertus Gysbrecht’s trompe l’oeil paintings with fabric do. I’m a strategic rather than virtuosic painter. But I don’t want the word ‘strategic’ to give the impression that the process is strictly cerebral. For me, thinking like an engineer does not mean thinking only in a cold way. There is a completely visceral, right-brained part of my painting process that I can’t explain. It’s that unnamable sensibility that guides my selection of colours, which are an increasingly important part of the paintings. It’s also that hard-to-identify sense that steers me into harsh editing at the end. I paint and paint and then destroy nine out of ten paintings. And I can’t say what I’m editing for; I just know it when I see it. My standards are increasingly hard to meet.

CB Could you expand on this intuitive aspect? Are you referring to something metaphysical, even spiritual (an unfashionable term, I know)? Or simply the idea that an intuitive, physical intelligence sometimes overtakes your process? Do you think this is specific to abstraction?

TA Awesome question, and one that keeps coming up! And every time the conversation runs up against the same thing: a dearth of good words for what we are trying to discuss. The word ‘spiritual’ is not only unfashionable, it’s contaminated by a host of unsavoury associations, but worst of all it’s just too dang general. And when something is hard to describe, like the ‘thing’ we’re talking about, it’s a mistake to assume that it lacks specificity. For me, this part of my thinking could best be described as running parallel to the spiritual, but contiguous with the physical and the rational. It’s not a cerebral operation, but it’s not at odds with the cerebral either. They support one another. It’s the part of you that can know something to be true without knowing why. It’s like a sense of equilibrium; even with your eyes closed, you can sense that you are straight up and down.

Details of the show at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis and the dates of the exhibition at Malmö Konsthall, Sweden in the bio for Tauba Auerbach corrected 22 February 2012.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 145 with the headline ‘Dear Painter...’.