In the Flesh

Jennifer Higgie visits Carol Rama’s studio in Turin, Italy

Jennifer Higgie visits Carol Rama’s studio in Turin, Italy

‘I discovered that painting freed me from the anguish at everything that society loosely indicated as transgression. I can't deny that I was fond of this game and took it to extremes. Always. Wherever I was. When I sang ... when I painted. When I associated with the aristocracy. Or the horse-racing set. Or that of painting. I was outside. Against. Never aligned.’ 1

Her house is filled with the erotics of anxiety; drawings and paintings of limbs, severed or prosthetic, of dentures and bedsteads, of the inner tubes of impotent bicycle tyres, flattened in paintings like strips of skin or dangled in dim corners like flaccid penises or intestines. The bodies she pictures refuse to give up; even smashed open or chopped up, still they struggle to survive their strange, sad love affair with the world; craving a kiss even as they know a kiss will break their astonished hearts.

Although it is not yet night, in the rooms of her apartment in Turin it is permanently dusk. She has lived here alone for 60 years. The windows are covered up; the air is thick with an atmosphere of something remembered and felt so hard it must assume a shape – a repeated drawing of a face, say, or a mad decorative cow or, as if in a desperate bid for order, winged, entwined bodies painted over the tranquil logic of an architectural plan. On walls and tables images of floating limbs and red-lipped faces drift in the ether like expatriate souls looking for somewhere reasonable to rest.

But she cannot rest. She is old now but very busy. Her desk is brightly lit; the glow of her lamp seeps into the dim corners around her; when no one is talking, the charged atmosphere of her home is as hushed as a waiting room. Objects here emanate the soft glow of things known and well loved; tired, but even after all these years still not exhausted by touch. She serves small chocolates wrapped in gold paper; as she eats one, she explains that frogs are the only animals that have really meant something to her. They lived in the rice fields near to the place where her mother had a house.2

‘I've always loved objects and situations that were rejected. When I was about six, I used to sleep with a frog that clung on to me. When my uncle Edoardo explained to me that it clung on to me because it was a cold-blooded animal, I cried all day long because I had thought it was an amorous relationship.’3

Despite the gloomy calm, the walls are restless with an imagination that refuses to allay confusion with conventional reason (confusion can sometimes be its own conclusion). Images throb with the melancholy elation of dislocation – lonely, yet oddly peaceful amputees lie recumbent; vibrant tongues poke from faceless lips; sorrowful heads sprout flowers. Her most treasured drawing is a small one of her father, who was a manufacturer of automobiles and unisex bicycles. It hangs by her bed. She made it in 1939, when she was 21. Her father wears a crown of thorns; his head lingers above what appear to be razor blades. This was made a few years before he committed suicide.

Nothing new resonates like old things do. She likes objects that are damaged or worn because they ‘give you the idea they've been used’. 4 She is small and polite and wears a thick plait across the top of her head. Around her neck dangles a double-headed bronze penis. It is, she says, the first thing she puts on in the morning and the last thing she takes off at night.

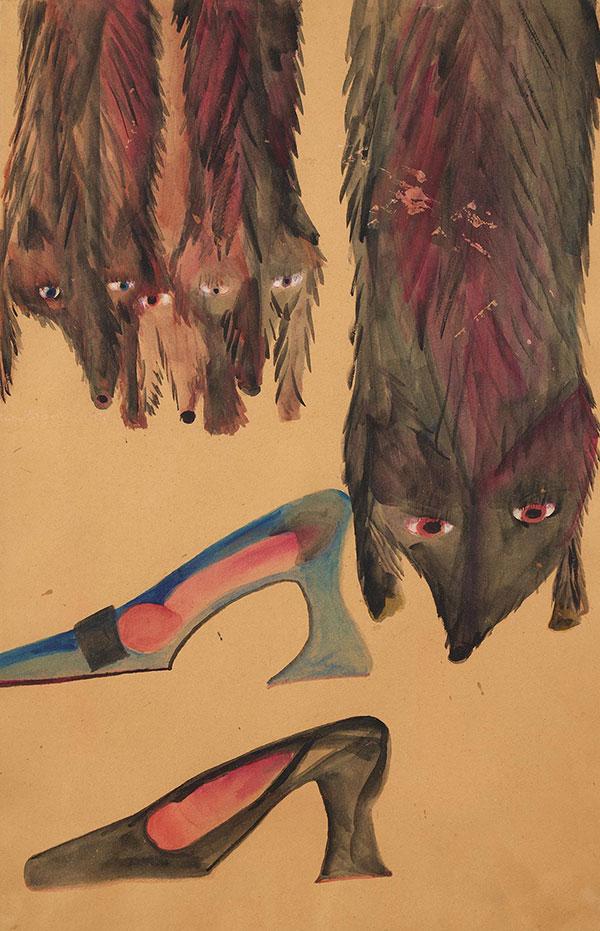

Her earliest pictures are from the 1930s. Rendered in oil and watercolour, metal, rubber, wire, cloth, lipstick and nail polish, some of the images are clumsy: the residue of a struggle to lend unfamiliar materials the shape of a feeling. In 20 or so self-portraits painted in oil on canvas her face is either oversimplified and flattened into decorative, childlike approximations or abstracted into a painterly, featureless blob; the borders between her skin and the world melted into an atmosphere thick with viscous colour. The watercolours, though, dramatically change pitch and tone. Delicate and fleshy, she treats the medium with a light touch; translucent yellows, bright bursts of red, soft blues and dirty whites flow in fits and starts over monochrome fields. Her focus wanders between the shop and the home: she paints shovels, shaving brushes, furs, shoes and urinals; bedsteads and bicycles, prostheses, wounds, wheelchairs and rags; fragments of still lifes, the intimations of absent, damaged or ornamented bodies.

Then her gaze shifts from what is around her to who she is; what she most fears and most wants. As if with a dreamy shudder, the body flings off its armour and reveals its damage; flesh solidified into fantasies nurtured on death and rebirth. Young women with blooming skin and pink tongues, vivid mouths and flowers in their hair inhabit a Sadean world in which they are crippled or limbless; inert, shitting, dreaming or masturbating.

‘Private circumstances put me in a state of psychological amputation and loss. I understood I was obeying a mechanism of pain. And that, when I turned it on its head, it became a sort of devotion to pain, to joy, to death.’ 5

Her first show, in Turin in 1943, was closed before it opened, on the grounds of obscenity. (She says, ‘I love fetishes, sex. Sex dreamed about, fantasized about. The everyday objects that give pleasure, that cause dismay and eroticism in everyday life.’ 6) Although the heavy eyes and raw vaginas of the women she paints are like two planets at the centre of a visceral universe, every part of their bodies and the environments they inhabit is animated to varying degrees; the hierarchy of sensation shifts with every picture. (There are no borders between the demands and punishment of the flesh here, no matter how contradictory. Again and again orgasms inflict little deaths. The tension is palpable – the rapture and then loss of sexual connection; a simultaneous fear of, and desire for, intensity.) Many of her pictures include images of men frantically masturbating in close proximity to women; their bodies, except for their fierce penises, delineated only by a delicate line. In another series of drawings a woman is repeatedly penetrated by a snake. In a portrait of her grandmother eight sucking black leeches cling to her neck; her head is framed, surrounded by what appear to be wooden cobbler's tools. But somehow this nightmare world is surprisingly lacking in cruelty; these women appear to have defiantly granted the world their quizzical permission to do to them what it will. Nothing here is whole, complete or resolved, yet none the less mystification seems preferable to closure – it is, after all, the nature of closure to slam the door in the face of emotional, erotic or creative potential. Yet these women gaze out of the prison of their picturing seemingly less preoccupied with how to escape than with what they can do with their bodies here and now; as if flesh is a concept they're attempting to understand. (These are ideas that have been around for ever – the ones that say we are fragile and perplexed and cannot sit quietly alone in a room – and yet still, reasonable behaviour continues to elude us.)

Consider the time and her gender – a young unmarried woman living in a country ruled by a fascist dictator; by the time she turns 21, Europe is at war. There is a glorious obstinacy in these pictures to either self- or state censorship; one that insists on attempting to express the unspeakable.

Even now, almost 70 years later, she returns again and again to the body; it has never ceased to awe and bewilder her: what we can do to it; what other people desire to do it; what it can do back.

The world outside her dark apartment intrudes in cracks of light; in painted rocks and dentures; in photographs of her younger self; in the objects that could only come from somewhere else, made in factories or sold in shops, like nail polish or bicycles. The past in this house feels like a fragile ghost that needs to be nurtured, the present a state that continues its conflict with time. On an easel sits a small stack of cigarettes, for guests. Her home is strangely welcoming. This is somehow reassuring.

On the wall by her bed, next to the picture of her father, is a poem Man Ray made for her; 'Femme de Sept Visages' (Woman with Seven Faces, 1974). It is a short poem; like a drawing of the shape of words, her name is repeated and rearranged; as if emphasizing that the concise semantics of what she is called can only intimate who she might really be.

(Where were you when he did it? I asked. I do not remember exactly, she said. But it was by the seaside. What was he like, Man Ray? He knew how to love. He knew how to say I love you.)7

Modernism now is not important for her – not so much rejected as an irrelevance, simply one more orthodoxy to react against and then reject. In the 1950s, however, she was a member of MAC (Movimento Arte Concreta) which began in Milan in 1948. She said she ‘wanted to wean myself from that excess of freedom for which I had been criticized’. 8 Within the rigid principles of the Concrete canon, her often beautiful paintings are sparse and earthy; yet still they echo the curve and texture of skin; as if the body was still taunting her, hovering in the wings of her imagination. When she returned to it, it was with a vigour that expressed an exhausted relief.

In the 1960s she mainly made 'bricolages' – semi-abstract collages; it was a term coined for her by her friend the poet Edoardo Sanguinetti. He took his definition from Claude Lévi-Strauss: ‘Bricoleur: he who executes a work with his own hands, using different means from those used by the professional.’ Fingernails, teeth, claws and fake eyes explode across the picture plane like cosmic eruptions pertaining to sight, touch and taste. Blobs and stains litter these pictures; the detritus of the world elevated to a grubby celebration of life's grubbier aspects – the ones that usher in mess as an all-too-human attribute.

‘I didn't have any models for my painting; I didn't need any, having already four or five disasters in the family, six or seven tragic love stories, an invalid in the house, my father, who committed suicide at the age of 52 because he had become poor and been made bankrupt and no longer had the life he wanted, and I, it's very sad, felt his guilt. They're all things that were enough for me to have subjects to work on ... I didn't have any painters as masters, the sense of sin was my master.’ 9

I can imagine her making pictures without knowing exactly why, and not minding; of reaching out for things just within reach; the physical world as a lifeline. Art is not an ideology as much as a way of healing herself, and, with appropriate empathy, hopefully others; of acknowledging and so exorcizing difficulty. Biography here is intrinsic to meaning; it is the story you own that makes you who you are, that prompts you to make the pictures you choose to make. For her the enigma of the image is more articulate than the pinprick of words. Everything she feels, she attempts to picture – even the piteous expectation of clarity in ambiguous situations. (‘I have to chop up either the figure or the animal, like a private tragedy which I then hope to make less tragic by the colours and by the way of painting it.’)10

The world she describes is driven by a kind of solipsistic folklore – one in which the magical properties of ordinary objects and everyday bodies are ripe for a transformation into a meaning that can only ever refer back to their source material – herself and hopefully, by association, someone else.

1. Edoardo Sanguinetti, Carol Rama, Luigina Tozzato and Claudio Zambianchi (ed.), Franco Masoero Edizioni d'Arte, Turin, 2002, p. 62.

2. Author in conversation with Carol Rama, April 2004.

3. Tozzato and Zambianchi, p.136.

4. Ibid., p. 38.

5. Ibid., p. 100.

6. Ibid., p. 71.

7. Author in conversation with Carol Rama, April 2004.

8. Carol Rama, Skira, Milan, 2004, p. 38.

9. Tozzato and Zambianchi, p. 73.

10. Ibid., p. 109.

Main image: Carol Rama in her studio. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons