The French Far Right Shut Down a Muslim Rapper’s Bataclan Gig; Here’s Why That Should Scare You

If Macron and his administration do not control the public narrative of Muslims in France, someone else will

If Macron and his administration do not control the public narrative of Muslims in France, someone else will

Marine Le Pen finally has reason to celebrate. After she and her French far-right party suffered a landslide presidential defeat last year, a subsequent personnel exodus, and the recent necessity of rebranding from the National Front to the current ‘National Rally,’ she achieved a political win last Friday. ‘The cancellation of the @Medinrecords Bataclan concert is a victory for all the victims of Islamist terrorism,’ she tweeted. ‘This provocation had no place in this room, given its painful history.’

The erstwhile presidential candidate was referring to the French-Algerian rapper Médine and his decision to cancel two sold-out performances scheduled for October at the Bataclan, the Paris concert hall where 90 people were killed on 13 November 2015, by Islamic State terrorists. The cancellation came after pressure from a petition launched in June by a member of Le Pen’s National Rally party, which chastised the artist’s ‘violent lyrics in the name of Islam.’ Allowing Médine to play at a historically charged site like the Bataclan would, the petition said, be ‘the height of indecency and submission.’ The petition gained well over 30,000 signatories. The concerts have been rescheduled at Le Zénith, a different Parisian venue.

‘Out of respect for these families and to guarantee the security of my audience, these concerts cannot go ahead,’ Médine wrote in a statement posted on Friday, confirming his decision to cancel. The Bataclan said, in its own statement: ‘the freedom of expression of artists […] must remain a fundamental right in our democracy.’

Born Médine Zaouiche in Le Havre, in northwest France, Médine is a practising Muslim and a sometime critic of French attitudes towards Islam. The controversy surrounding his now-cancelled Bataclan performances stemmed largely from his 2015 song ‘Don’t Laïk,’ a jeu de mots of ‘don’t like’ in English and ‘laïcité,’ French for secularism. The song includes the lines, ‘I put fatwas on the heads of idiots’ and ‘crucify the [secularists] as in Golgotha,’ referring to the site of Jesus’s crucifixion. The cover for his 2005 album called ‘Jihad’ was also cited by the petitioners, especially for its use of an image of a sword in place of the letter J. (The album, however, seems to be as existential as it is political: its subtitle is, ‘The Biggest Combat is Against Yourself.’)

What is unspoken but implicit in this controversy is that more than any specific lyric or album visual, it is Médine’s identity – descended from North Africans, and a practising Muslim, which, through his music, he is vocal about – that the French far-right has, in this instance and many others, conflated with terrorism and the Islamic State. What is even more distressing is watching how centrists, too, have gone along with it.

Philippe Duperron, president of 13onze15, an organization that supports the November 2015 Paris attack victims (the name is a reference to the attack’s date), told Le Figaro that he hoped the Bataclan performance bookers would have ‘more tact and delicacy in their choice of programming.’ Even Gérard Collomb, France’s Minister of the Interior, hoped Médine would cancel the shows. ‘There is the freedom of creation, but we must not underestimate what may be such remarks on fragile minds, on a number of our young people,’ he said in June, even threatening to federally ban the concerts. ‘We are not in charge of the Bataclan’s programming, but as you know, anything that might bring a disturbance to public order can, within the limits of the law, earn a ban.’

These responses represent not only a problematic conflation of Islam and radical Islamic terrorism, but they also pose a danger to all Muslims in France. Le Pen and others claim that cancelling these concerts will, as Patrick Jardin – a father of one of the November 2015 victims, and vocal critic of allowing Médine to perform – put it, avoid ‘blood running again at the Bataclan.’ Jardin describes himself as ‘apolitical’. But this kind of pressure on a Muslim musician also sends a message: that to be an outspoken Muslim in France and to even hint at criticizing secular, republican values is to be, at best, disrespectful of those who died at the hands of the Islamic State, and, at worst, an active danger to the French public. That there has been little discernible pushback to the petition from powerful politicians who are not on the far right is unfortunate.

It would perhaps be too much to expect comment on this from the president, but Emmanuel Macron has kept perhaps too quiet on the subject of Islam. At the beginning of the year, he did say he was working on a ‘structuring of Islam in France,’ in which the goal was to ‘preserve national cohesion and the possibility of having free consciousness.’ After continually pushing back his announcement of what that might look like, Collomb came forward in June to say that France’s Muslims would subsequently be consulted vis-à-vis organizing ‘Islam within the framework of our Republican institutions,’ which sounds like the standard narrative of integration employed by previous governments.

We are yet to see what kind of precise policy might come from this new ‘framework,’ but Macron does have consultants on the subject who have already provided him with some surprising and sensationalist claims. One of them is Hakim El Karoui – a Paris-born, Tunisian-descended professor and government advisor, who was raised in both Muslim and Protestant Christian traditions – who conducted a study titled ‘A French Islam is Possible’ for the Institut Montaigne, a French think tank that bills itself as politically independent. El Karoui is close to Macron, and has his ear, according to numerous reports in Le Monde and L’Express.

In the study, El Karoui concluded that 28 percent of French Muslims are ‘authoritarians’ who define their religion as ‘a mode of rebellion against the rest of French society.’

The study’s methods are insufficiently robust. The study surveyed only 1,029 French people, 874 of whom identified as Muslim, and made serious categorical leaps based on their answers. For instance, the study splits French Muslims into six categories, half of whom are characterized as not sufficiently favouring Republican values. The 28 percent statistic comes from the fifth and sixth categories, in which, the author writes, ‘the vast majority do not think that religion is solely a private matter, and most are in favour of religious expression in the workplace’ and, for the sixth and most ‘authoritarian’ category, ‘almost all are in favour of the niqab, while almost 50% are against secularism and for religious expression in the workplace.’

Together, these fifth and sixth categories – the 28 percent – represent only about 245 self-identifying Muslims living in France. To make the claim that 28 percent of all Muslims in France are defining their religion as ‘a mode of rebellion against the rest of French society’ based on an interpretation of 245 people’s answers is misleading, to say the least. Even El Karoui seemed to understand the problems inherent in his study, noting that the study faces ‘limitations,’ and that ‘the average margin of error for a survey done with a sample of 1,000 people is approximately 3%, and when looking at a sub-group of this same sample, this margin significantly increases to 6-8%. The information it provides is a reflection of views held at the time of the survey and does not serve predictive purposes.’

But these facile statistics were nonetheless used to support other contentious, even predictive claims. Under ‘key findings,’ the study states that ‘a majority of Muslims in France adhere to a system of values and a religious practice which can seamlessly co-exist within the corpus of the French Republic and nation (46%)’; but, it adds, ‘an ever-increasing number of young Muslims, although they remain in the minority, identify above all with a disaffected form of religious affiliation (almost 50% of 15–25 year-olds).’

It is fair to worry about the type and quality of counsel Macron is getting when it comes to French Muslims. These statistics in particular are weak at best, and although I believe El Karoui’s work should be taken in good faith – his stated desire is to ‘preserve social cohesion and national harmony’ – it is also vital that Macron and his government receive the most accurate and least sensationalized information. France in particular has had exceptional tensions between Muslims and non-Muslims, and given that, since 2013, over 1,700 French nationals have gone to fight for the Islamic State, there are no doubt serious issues with integration. Due to these circumstances, the French government’s hand has been, in part, forced into creating policies and a cultural atmosphere, with regard to its Muslim population, that are focused on stopping terrorism and defections to the Islamic State. Hearing that well over a quarter of the French Muslim population is attempting to use their religion as a form of ‘rebellion’ against the state will not lead to more productive policies. Instead, it seems likely to only intensify decisions. The narrative of French Muslims must be accurately written.

Still, it is difficult to say how the best policies might be engineered. ‘Macron entered office in 2015, on the heels of recent terrorist attacks,’ Bernard Godard, a former consultant on Islam for the French Interior Ministry, told The Atlantic recently, referring to the president’s earlier job as Minister of the Economy, Industry, and Digital Affairs under then-president François Hollande. ‘For French public opinion, organizing Islam needs to be a security question […] but concretely, we don’t know what that means.’

What has been made concrete – underscored especially by Médine’s concert cancellations at the Bataclan – is that if Macron and his administration do not control the public narrative of Muslims in France, someone else will. ‘On social media, or in the public debate, who talks about Islam, who talks about religion?’ El Karoui recently wondered. ‘We need another public narrative on Islam.’

In this, he’s right. The trouble is that the far right is all too happy to create that new narrative, especially if the vacuum continues to be left unfilled, or the centre is simply content to go along for the ride.

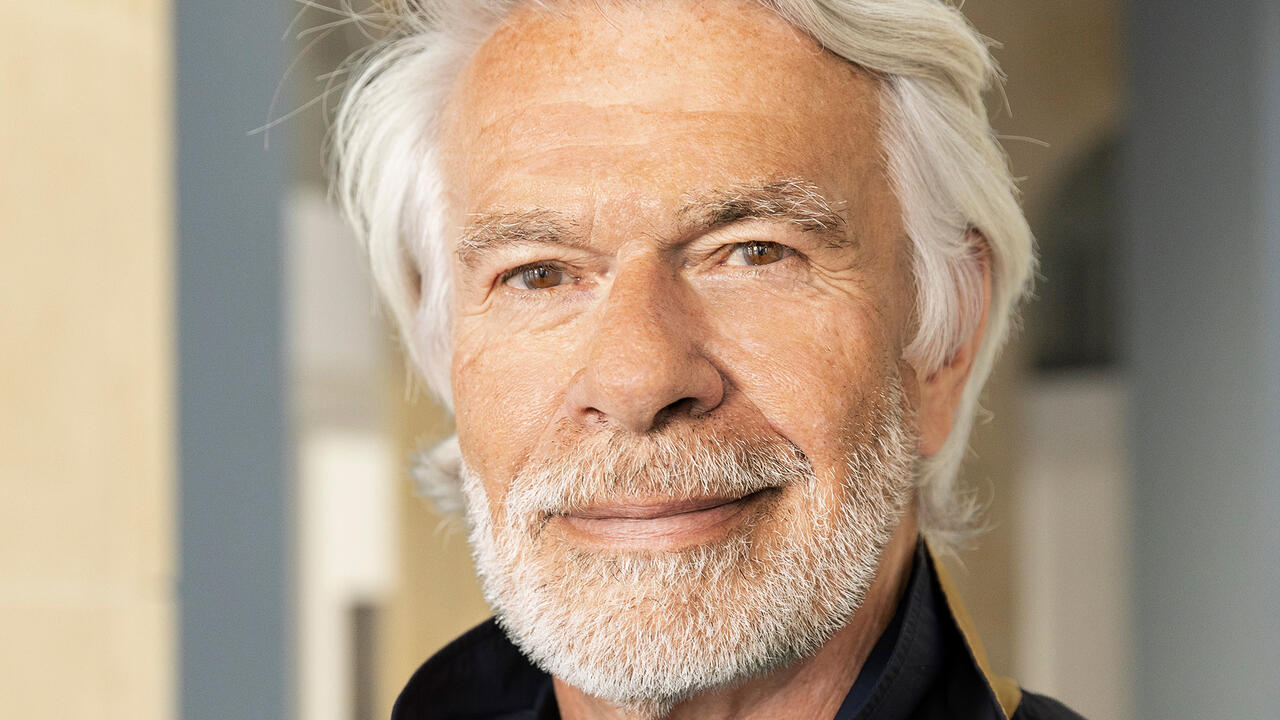

Main image: Médine, Bataclan, 2018, film still. Courtesy: the artist