Frida Orupabo Preaches to the Choir

At Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm, the artist's collages destabilize the notion of the Strong Black Woman

At Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm, the artist's collages destabilize the notion of the Strong Black Woman

The title of Frida Orupabo’s solo exhibition ‘How Fast Shall We Sing’ is borrowed from a 1957 issue of The Instructor – a devotional magazine published by the Church of Latter-Day Saints. Linking this phrase, which evokes the tradition of the Black Spiritual church choir, to the trope of the Strong Black Woman, Orupabo builds on a legacy of Black feminist thinkers who maintain that idealized representations of Black women’s strength mask the injuries wrought by racism on her body and psyche. The implication here is that, no matter what is done to her, the Strong Black Woman will sing as fast as the choirmaster requires.

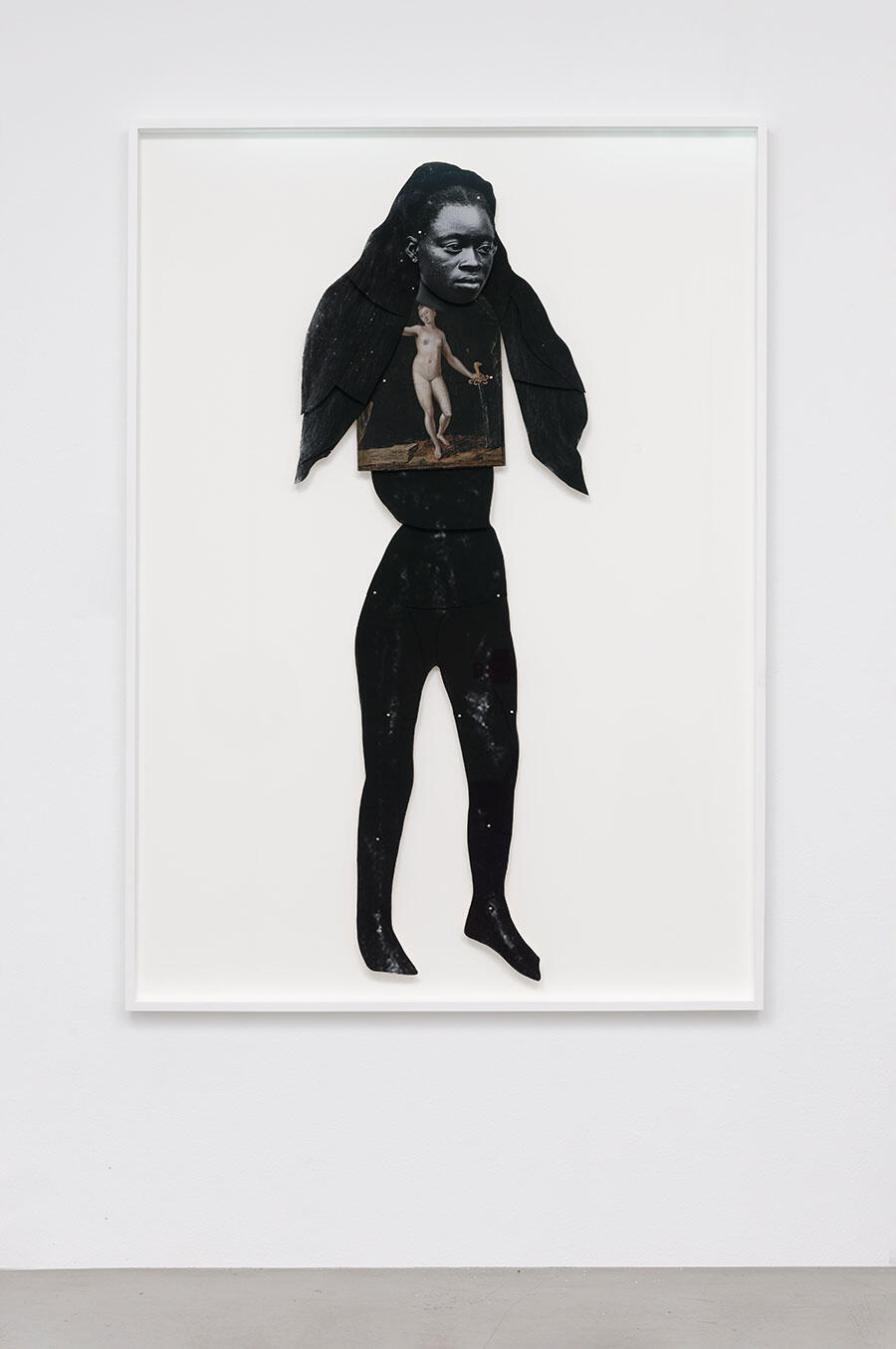

The contours of that trope – as well as the white violence it obscures – is clearly articulated in Orupabo’s choice of source imagery. She juxtaposes historical photographs of enslaved Black people drawn from internet research with Renaissance paintings and historical fashion photography. In Woman II (2022), for example, a Black figure’s chest cavity is made up of a painting depicting a nude white woman-child wielding a large sword. Tilting her head inquiringly, her back arched slightly, she offers the soft creamy skin of her chest and abdomen to the viewer as though to prove her innocent playfulness. The figure in which the nude is lodged looks away, her expression muted and unreadable. Orupabo has given her no arms with which to grasp a sword.

Despite the strength of these images, Orupabo most powerfully destabilizes the notion of the Strong Black Woman on a formal level. The face of Woman head / long hair (2022), for instance, comprises prints of the same photograph. The top print extends to just beneath the woman’s eyes, which gaze to one side with a soft, melancholic tone. The second print is perfectly positioned beneath the first so that no discontinuity in the structure of the image is discernible. Instead, the cut between the top layer and the bottom layer is like a line drawn across the woman’s face, running across the bridge of her nose, separating the part of her that watches from the part of her that testifies. Orupabo’s almost-invisible deployment of collage here creates layers in historical imagery that thickens their meaning by multiplying their surfaces.

Another formal mechanism Orupabo employs to collate images in a way that makes structural violence explicit is the split-pin: the near-obsolete metal fasteners used to keep paper files together. One especially striking example is Horse Girl (2022), in which the pins have a double function. Positioned at the body’s joints – elbows, shoulders, wrists – they both connect images to form the figure and suggest the possibility that Orupabo’s construction could move given the right circumstances, haunting Horse Girl with a mobility that is nevertheless denied to her.

Installed along the west wall of the gallery, the aforementioned Woman II forms an imposing triptych with Woman I and Woman III, in which the artist uses the same face in each composition. Withholding her gaze from the photographer, the woman appears emotionally absent in the manner of those who have endured great pain. The visual reference to trauma is clear, yet the most developed aspect of Orupabo’s work in ‘How Fast Shall We Sing’ is not the representation of violence, but her notion of Blackness as morphological – something to be constructed, deconstructed and reconstructed. The resulting figures attest to Orupabo’s own curiosity, repulsion and desire as much as – if not more than – they reflect on the disfiguring effects of the white gaze.

Frida Orupabo’s ‘How Fast Shall We Sing’ is on view at Nordenhake Gallery, Stockholm, until 14 May.

Main image: Frida Orupabo, ‘How Fast Shall We Sing’, 2022, Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm/Berlin/Mexico City; photograph: Carl Henrik Tillberg