‘Geographies of Imagination’ Argues for a Different Way to Decolonize

At Savvy Contemporary, Berlin a group show reveals how decolonization has become a buzzword in progressive museum programming

At Savvy Contemporary, Berlin a group show reveals how decolonization has become a buzzword in progressive museum programming

The decapitated clay bust of the Belgian explorer Constant de Deken lies crumbling on the floor. Opposite, an untarnished rubber iteration of the same figure glowers. Produced by Ibrahim Mahama, the sculptures, facing off in the bustling subterranean library of SAVVY Contemporary, reference a statue in Antwerp that shows De Deken subduing an enslaved Congolese man. Mahama’s deformed appropriations deconstruct the usual function of public monuments, which aim to make history appear inviolable. The counter-monuments were produced within a searching, circular discussion group, documentation of which plays on a nearby monitor. Written on a board in the background are the words: ‘Colonialism is not taught because colonization has never ended.’

Colonization hasn’t ended because it structures civic life. In Europe, cultural institutions are some of colonialism’s most enduring monuments. Not only do they foreground a regime of representation grounded upon alterity and exoticism, they also dynamically morph to co-opt critical challenges, perpetuating colonialism as a temporality in the present. That decolonization has become a buzzword in progressive museum programming is itself a settler-colonial paradox: a robust commitment to the matter might begin with de-accessioning, not discussion.

‘Geographies of Imagination’, a group exhibition accompanied by a series of event-based ‘invocations’, proposes a different institutional paradigm, in which artworks are not rarefied products of an existing system, but agents that reconfigure their foundational conditions. In its entrance corridor, the Pan-African collective Chimurenga’s dazzling ‘New Cartographies’ (2015–ongoing) – a series of real and imaginary charts that radically and emphatically centre Africa – emphasize that remapping must be literal before it can be metaphorical. These posters are twinned with a hand-drawn timeline, which includes a range of occurrences, from the 1791–1804 Haitian Revolution to the development of FRONTEX, the EU’s European Border and Coast Guard Agency, in an attempt to visualize the intellectual and social formation of Germany. Enticingly noisy and teleological, the entryway rebukes muted modernist display conventions, which tend to valorize autonomous art objects, isolated and estranged from history.

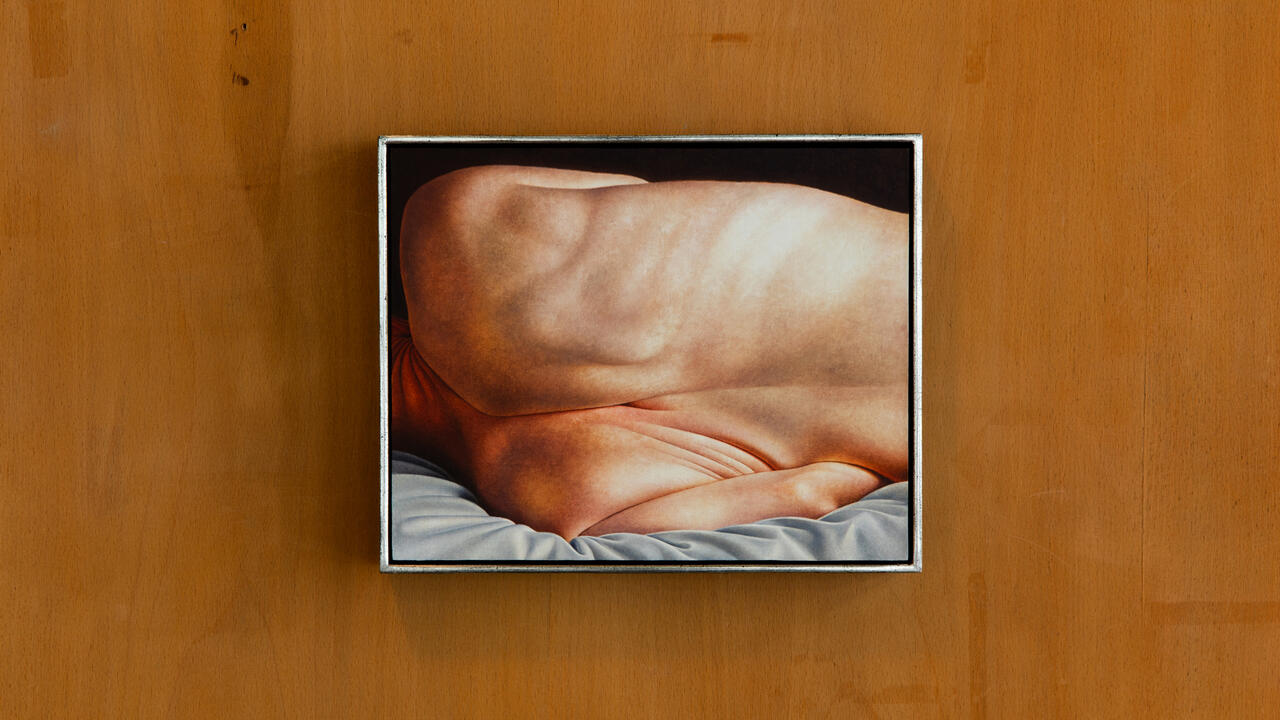

Mostly, the installations disorder, rather than organize, information – like landscapes rather than maps. ‘They Don’t Care About Us’ (2016), a series of photo portraits by Mahir Jahmal depicting Vienna’s black communities, are emotively hand-crumpled, the images buckling as if entrapped by visibility. Jahmal’s photographs suggest that it is not only representations of those in power that must be dismantled, but representation as a system of power. In Saddie Choua’s Am I the Only One Who Is like Me? (2017), monitors, leant against cardboard boxes and record covers, loop fragments of recorded newscasts and pop media, exposing how frivolity and racism are co-constitutive in the white imagination.

Situated within a curatorial schema of ‘dis-othering’, ‘Geographies of Imagination’ attempts a ‘self-break’, as the exhibition’s literature terms it, from practices of othering within cultural production. In the art world, at least, the cartographic imperative of postcolonialism remains a movement outwards. Feverish, the market demands more fairs in more locations and more artists from more locations, devouring all. Rooted in dismantling a system built to exclude, the self-reflexivity of the exhibition’s critical lens is eviscerating.

Daniela Ortiz’s ebullient children’s book, The ABC of Racist Europe (2017), presented as an anti-racist abecedarium arranged on the wall, as if in a pre-school, utilizes collage and simple messaging to challenge the ways in which oppressive thinking is endemic in even the earliest introductions to language and epistemology. The turn inwards suggests a dystrophic psychogeography in which not just monuments and maps, but the process of subjectification itself, might be re-imagined. To end on Ortiz’s letter ‘E’: ‘Even though European people invaded with violence the global south, even though the British Empire Economy was built through oppression and Exploitation of people from the colonies, Empowerment and resistance will be always stronger than the colonisers.’

'Geographies of Imagination' was on view at SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin, from 13 September until 11 November 2018.

Main image: Saddie Choua, Am I The Only One Who Is Like Me, 2017, mixed media installation. Courtesy: SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin; photograph: Raisa Galofre