Giovanna Silva on the Challenges of Photographing Iconic Buildings

The celebrated artist is interested in the role of modernism in statecraft and conflict

The celebrated artist is interested in the role of modernism in statecraft and conflict

This piece appears in the columns section of frieze 244, ‘Built Environment’

For me, photographing architecture provides an opportunity to speak about the history of a country, or to tell the story of a specific place and moment in time. I originally studied to become an architect in Milan because I wanted my work to take me around the world. But I soon realized that, aside from the likes of Renzo Piano, very few architects get to travel globally making buildings. So, instead, I started to shoot buildings, eventually contributing to magazines like Domus and Abitare. Later, I decided that I wanted to work in a more creative way, so I began producing books that combined architecture with travel; I also started my own publishing house, Humboldt, that focuses on books related to travel or collaborations between writers and photographers.

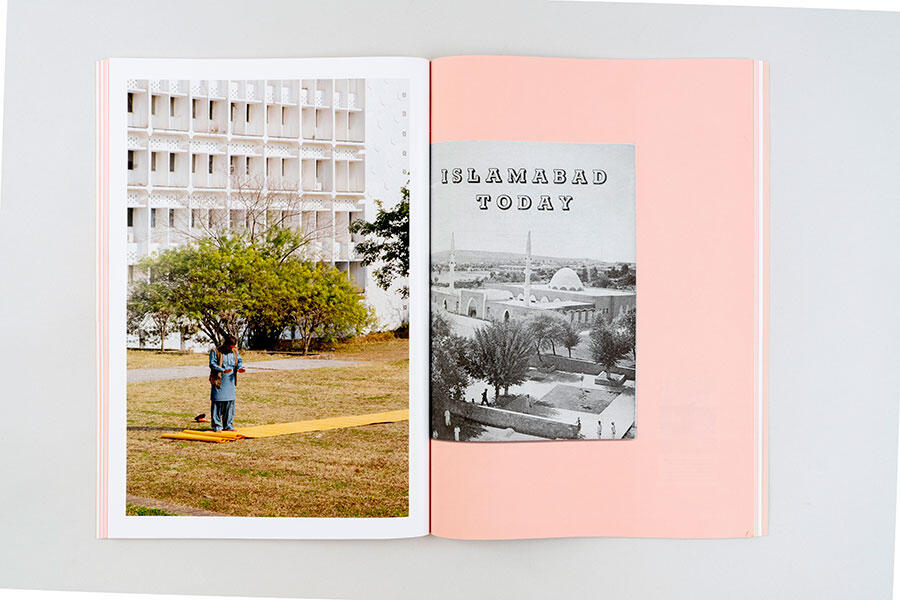

I’m interested in the role of modernist architecture in statecraft and nation-building, as well as in the way it can register conflict. I travelled to Islamabad, for instance, to photograph a complex of ministerial buildings designed in 1962–64 by Gio Ponti, one of the most important Italian architects of the 20th century. After Pakistan gained its independence in 1947, the country decided to build a capital city, almost from scratch, and I wanted to use photographs of Ponti’s architecture to speak about Pakistani independence, the creation of Islamabad and the country’s wars with India.

In 2017, I went to Cambodia because I was interested in the Cambodian architect Vann Molyvann, who was commissioned by the country’s then-leader, Norodom Sihanouk, to design a number of buildings – among them the Council of Ministers (c.1950), the National Sports Complex (1964) and the National Theatre (1968) – before being forced to emigrate to Switzerland following the 1970 coup d’état.

I have also photographed Oscar Niemeyer’s unfinished architecture for the International Fair in Tripoli, one of Lebanon’s flagship modernization projects of the 1960s. This enormous site comprises 15 structures – including an amphitheatre, an arch, a dome and many pavilions – where other countries were to mount exhibitions, capturing an historical vision of internationalism. Designed by Niemeyer between 1962–67, work on the complex was not yet complete when the Lebanese Civil War broke out in 1975. The project was abandoned, but the shells of the buildings are still there, slowly deteriorating. When I visited, I was interested to see that the site was now being used by skateboarders. I’ve also photographed the destroyed remnants of Muammar Gaddafi’s house in Libya and Saddam Hussein’s house in Iraq to capture the visions of dictators and the aftereffects of war.

Taking pictures of I.M. Pei’s Louvre Pyramid (1989) posed a different sort of challenge because there are already images of it everywhere: on postcards, in books, in tourist selfies. I was in Paris for three days to shoot for the retrospective ‘I.M. Pei: Life Is Architecture’ at M+, Hong Kong. I waited for the perfect weather, but it rained the entire time. At one point, I saw a bride having her photo taken in front of the Pyramid and I captured her running towards it. I wanted to capture this iconic structure as a backdrop to daily life: tourists touching it, cleaning teams circling it, staff checking visitors’ entry tickets beside it. The commercial work I did in the past often required a very standardized approach: clean photographs taken with a wide-angle lens. If the building or the image wasn’t suitable, you just fixed it later in Photoshop.

When I started taking photographs for my own projects, I tried to depict the buildings as they really were; I looked for the less represented side of architecture, for people using or misusing a building in unexpected ways. If buildings are dirty or imperfect, that’s fine. That’s how they tell their real stories.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 244 with the headline ‘Tell It Slant’

Main image: Giovanna Silva, Islamabad (detail), 2020, from: 'Giovanna Silva, Paolo Rosselli: Islamabad Today', 2021. Courtesy: the artist and Mousse Publishing