Gregg Bordowitz’s Theatre of the Ridiculous

The activist and videomaker’s adaptation of Nikolai Erdman’s The Suicide (1928) is a production of pure absurdity in the face of mortality

The activist and videomaker’s adaptation of Nikolai Erdman’s The Suicide (1928) is a production of pure absurdity in the face of mortality

As a member of ACT UP during the 1980s and ’90s, activist and videomaker Gregg Bordowitz’s artistic practice was undergirded by a desire for immediacy and practicality – think Xeroxed flyers, DV cameras and VHS tapes. Often scathingly funny, Bordowitz’s videos showcase a flexibility for incorporating mixed media into a moving-image format, but his works are rarely overtly theatrical, since his primary motivation was to take control of the AIDS narrative and place it in the hands of the HIV-positive. Allegory and opulent production design are not necessities when your concern is saving lives through the dissemination of safe-sex education.

Bordowitz’s 1996 feature-length production of Nikolai Erdman’s The Suicide (1928) – a play thwarted by Josef Stalin’s censors in 1930 and consequently withheld from the public for decades – stands out in his body of work for this reason. Streaming through 28 September in conjunction with the MoMA PS1 exhibition Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna Be Well, the film is a more elaborate production than his safe-sex PSAs, produced with Jean Carlomusto, and his diaristic videos (many of which are currently on view at the exhibition). Filmed on a soundstage at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, on a set draped in charcoal-floral wallpaper, with professional stage actors and swooping curved dolly shots, what might at first glance seem an aberration in Bordowitz’s oeuvre speaks to the artist’s ever-present interest in cabaret and performance. In his anthology The AIDS Crisis Is Ridiculous and Other Writings: 1986–2003 (2004), Bordowitz opens the title essay by reprinting Charles Ludlam’s ‘Manifesto: Ridiculous Theater, Scourge of Human Folly’ (1989), which contains such axioms as: ‘You are living a mockery of your ideals. If not, you have set your ideals too low.’ Bordowitz goes on to recount a recurring fantasy of having unprotected sex with Ludlum, thus inheriting his legacy in tandem with their shared HIV status. His takeaway from this fantasy is the acceptance that there is no ‘reason’ behind the AIDS crisis, only a transference of ‘meaning’ from one generation of queers to the next. He goes on to describe how he incorporates these axioms, namely their anti-materialism and self-awareness, into his video work.

The Suicide conceives a relation with Ludlum in a more literal way; here, Bordowitz is adapting theatre, and it is nothing if not ridiculous. The useful anger (there is plenty of shouting in the production, but not much of it amounts to anything) and propaganda of his ACT UP videos are gone, replaced with a broiling dramatic irony. Through a series of woeful misunderstandings, a rumour spreads that an unemployed and hapless peasant named Semyon (Lothaire Bluteau, a rubber-faced live wire) is on the verge of killing himself. He is visited by a parade of local characters who offer him a litany of causes – knowledge, beauty, housing, nationalism, art, class – to which he should dedicate his death. ‘You’re going to shoot yourself? Splendid! By all means! But do so for the good of society,’ a member of the Russian intelligentsia urges. ‘Now more than ever we need dead ideologists.’ The comrades enter a sort of raffle organized by Semyon’s postman: Semyon will weigh his options and, at the end of a drunken banquet in his honour, announce his chosen cause before committing his final act. Intoxicated by the idea of being perceived as a hero for speaking against the Kremlin, Semyon allows himself to be swept up in the ploy. The allegory in Bordowitz’s rendering of the play is especially clear when considered in the context of his other works, which often included satirical scenes where the artist appears as himself, interviewed on hellish news programmes that praise him for being ‘brave’ and ‘a martyr’ for his diagnosis. Semyon’s impending fate is similarly a political football, a metonymic definition of the AIDS-afflicted as socially powerless.

The Suicide flirts with disaffection but does have one moment of hopeful redemption at the tail-end of Semyon’s ‘going away’ party: a klezmer-stomp musical number, lit by disco balls and flaunting an overhead camera angle. Accordions back an anthem for the lower class to continue enjoying life to spite the rich, with a Russian refrain of ‘party on, poor man’. Semyon’s final realization that ‘life is art’ also mirrors Bordowitz’s close friend Douglas Crimp’s writing in AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism (1987) that ‘art does have the power to save lives, and it is this very power that must be recognized, fostered and supported’. This is not portrayed as a lofty aspiration but as a basic tenet of human existence; that space can be held for both art and life, and that the two can intermingle freely, regardless of class distinctions.

The Suicide is not an elegy. It is not beautiful and its ambitions, in Ludlam’s language, do not ‘have the stink of art’. It is, however, rarer than that: a production of pure absurdity, a theatre of ridicule, in the face of mortality.

Main Image: Gregg Bordowitz, The Suicide, 1996, video still. Courtesy: Video Data Bank at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago

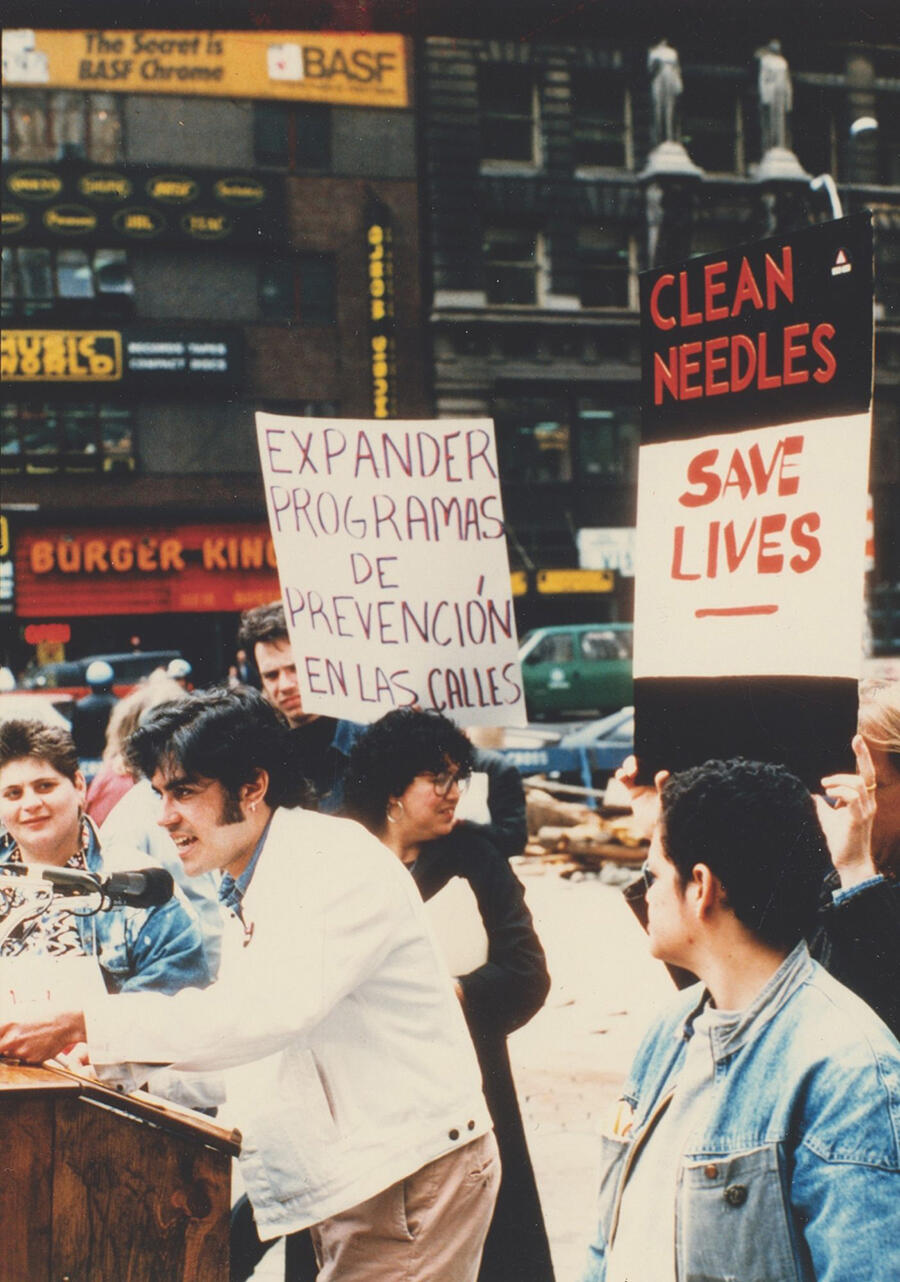

Thumbnail Image: Gregg Bordowitz addressing AIDS Activists during protest in NYC, 1988, gelatin silver print, 20 × 25 cm. Courtesy: the artist; photography: Lee Snider