Gustav Metzger Sees the Potential in Destruction

At the Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, the artist questions our unwavering faith in efficiency and development

At the Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, the artist questions our unwavering faith in efficiency and development

On an overcast winter day, in a park hedged by Frankfurt’s business skyscrapers, Gustav Metzger’s Strampelnde Bäume (Flailing Trees, 1999/24) comprises a row of lifeless, upended trees, their tops encased in concrete slabs, roots pointing upwards like bare branches. Blending with the tepid corporate architecture and the shrinking enclave of greenery dotted with public sculpture, these zombified trees mark the entrance to Metzger’s first museum retrospective in Germany. They are the least conspicuous yet most poignant monument to the delusion of unhampered civilizational growth. Strampelnde Bäume also serves as a reminder that Metzger’s practice was defined by being uprooted.

Born in 1926 in Nuremberg to a Polish Orthodox Jewish family, most of whom soon perished in the Holocaust, the artist was evacuated to the UK in 1939 on a Kindertransport shortly before the outbreak of World War II. His ‘auto-destructive art’, first articulated in the early 1960s, had widespread impact, propelling political activists to denounce war as well as The Who’s Pete Townshend to perform his signature act of smashing guitars on stage. ‘I misunderstood his manifesto when I was young,’ Townshend shared on his website after Metzger’s death in 2017. ‘Art should instead reflect the way we are destroying our world.’

The exhibition kicks off in a rather conservative manner with monochrome works on paper echoing Metzger’s early life. Scenes of affection (Family at the Table, 1950), images of pregnant women in pastel (Untitled, c.1948) and portraits of children in rough contour (Untitled, c.1949) are followed by colour-heavy renderings of three-legged tables in charcoal, pastel, pencil, watercolour, ink and oil (Table, c.1956) where the furniture transforms from a gathering place into an atomic mushroom. The sequence culminates in a set of newspaper pages; the broad strokes of pitch-black paint conceal the text, resembling hastily redacted documents (Untitled, 1960–61).

What follows is a constellation of acclaimed works highlighting links between Metzger’s lived experience and his uncompromising attitude. Installations addressing the Holocaust compel the viewer to confront archival imagery from a close, discomforting perspective. These include Historic Photographs: The Ramp at Auschwitz, Summer 1944 (1998/2024), a larger-than-life print of a crowd, led by uniformed men, displayed in a narrow tunnel, and Historic Photographs: To Crawl Into – Anschluss, Vienna, March 1938 (1996/2024), a massive snapshot of a group of people ordered to scrub the streets of Austria’s capital, placed on the floor and covered with yellow fabric. It is only visible by fumbling underneath the sheet on all fours – like the men, women and children forced into menial labour.

Neighbouring rooms feature works critical of the food industry, automobile manufacturing and air travel, attesting to Metzger’s growing concern over our unwavering faith in efficiency and development. For example, Mobbile (1970/2024) sees a car pumping exhaust fumes into a transparent container filled with plants. ‘It came as a deep shock’, he told Hans Ulrich Obrist in a recently published volume of conversations, ‘to realize there was a connection between the works I had been planning and the original Nazi experiments for gas chambers – but, deep down, I must have sensed that connection all along.’

Metzger was also wary of rapidly advancing digitalization. With artistic manifestos now being relegated to history books, letters of support weaponised to sow discord and digital algorithms pushing instant politics, his practice feels particularly pertinent. For Metzger, destruction was a means for conveying the urgency of a sustainable existence. The power of his work lies in critically examining how the tools of progress are deployed. It would have been fascinating to hear what he had to say about artificial intelligence.

Gustav Metzger’s retrospective is on view at TOWER MMK, Frankfurt, until 5 January 2025

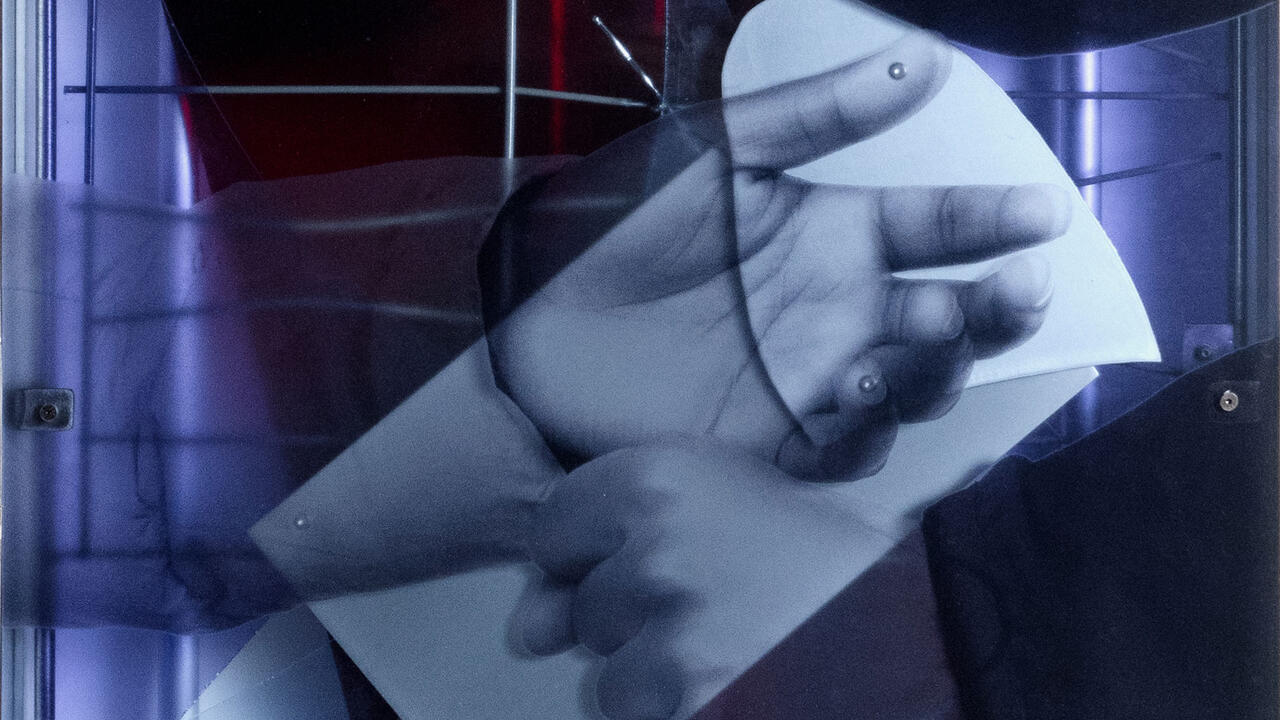

Main image: Gustav Metzger, Untitled, 1960–61, oil on newspaper; 28 × 20 cm. Courtesy: The Estate of Gustav Metzger & The Gustav Metzger Foundation, London and © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024; photograph: Axel Schneider