How a Dress Can Be More Than a Commodity

Fashion designer Molly Goddard and photographer Sarah Edwards turn garments into abstractions at London’s Chelsea Space

Fashion designer Molly Goddard and photographer Sarah Edwards turn garments into abstractions at London’s Chelsea Space

We know how the mind responds when it sees an image of a woman in a beautiful dress. Think of Queen Victoria opting to wear white at her wedding to Prince Albert in 1840, supposedly starting the tradition of bridal dresses in that colour, or pop star Jennifer Lopez in navel-grazing Versace green at the 2000 Grammy Awards – an outfit choice that inspired the development of Google Images, after prompting so many curious queries on the search engine. But what is the dress when it’s not being worn? Can it be explored by art, or is it best left to the realm of fashion? This is the subject investigated by the fashion designer Molly Goddard and her mother and collaborator, the photographer Sarah Edwards at ‘Dress Portrait’, at Chelsea Space.

Fashion always has an agenda. An unworn dress can evoke the same emotional responses as an artwork, but it usually does so in the name of commerce. The challenge inherent in photographing clothes is to avoid merely replicating the visual language of fashion editorial imagery. Fashion imagery can be as impactful as art, but it tends to come as a bonus rather than as its raison d’être. To photograph a dress, on or off the body, risks reproducing the template provided by commercial fashion magazines with conceptual limitations. Edwards began documenting Goddard’s work from the production of the designer’s first collection in 2014, and yet this exhibition does not contain a standard excavation of a designer’s processes. Instead we see images that recall early photography, garments rendered as still lifes alongside water, organic matter and antique floral textiles, and images of the dresses abstracted to blankness.

Goddard’s methods of approaching design and delivery have always been without convention. She began showing at London Fashion Week in 2014, in a series of off-beat presentations that saw models engaging in life-drawing classes or sandwich-making production lines, rather than traipsing up and down catwalks. This was a way of claiming a slightly more irreverent seat at the table: Goddard didn’t take herself, or her work, too seriously, instead offering the jaded industry insiders who attended her presentations a chance to relax, or perhaps even to laugh. After the first encounter, her design signature becomes instantly recognisable: the dresses are frothy confections of colourful tulle or satin, featuring shirred panels, ruffles and layers of smocking, and often in an exaggerated empire-line silhouette that flares outward from the chest.

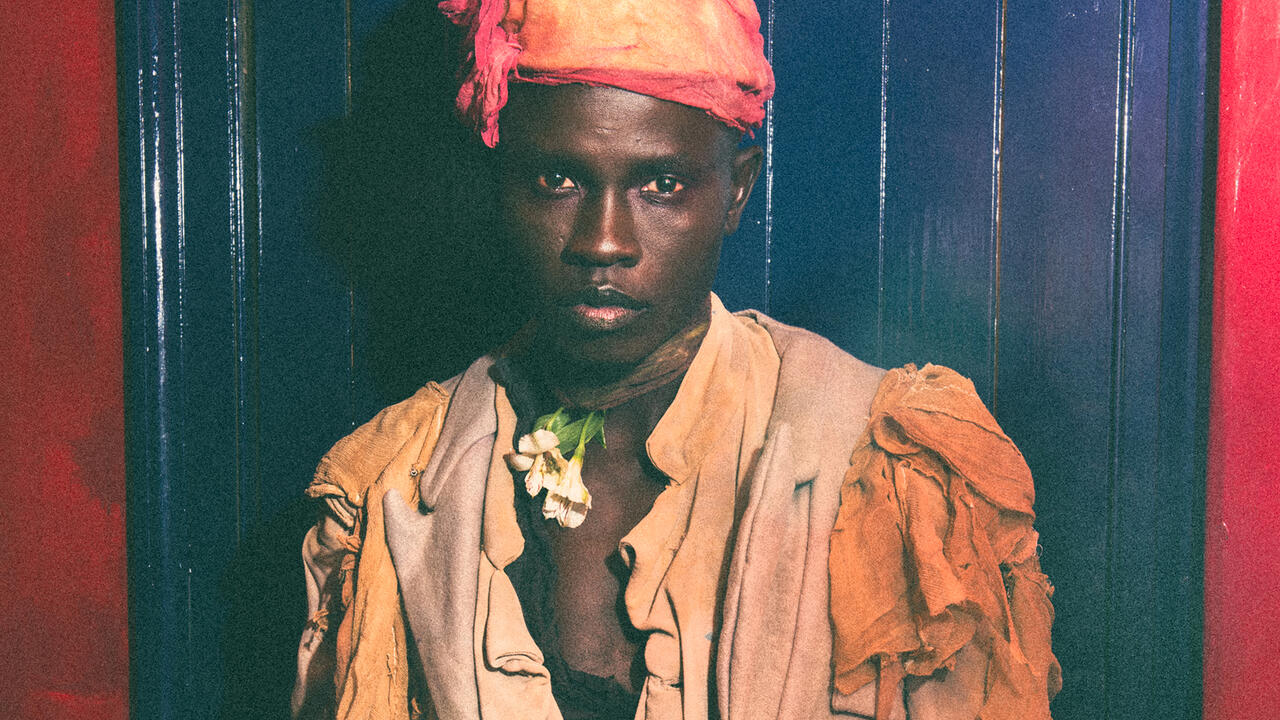

Edwards, meanwhile, was responsible for the set design at Goddard’s shows, turning parish halls into teenage proms and show spaces into street markets. Her eye on Goddard’s work is valuable, not in granting some behind-the-scenes access, but in revealing the interplay between garment and the world around it. These dresses are impossible to ignore; with their volume and fabrication, they come with a particular physical heft and don’t attempt to skim the body or flatter it along conventional lines. They cut through air and can captivate a room. Superficially playful, they also come with a deceptive gravity that goes beyond the prettiness of tulle and frills. At their best, the photographs are reminiscent of Nick Veasey’s X-rays of Balenciaga dresses, commissioned by the V&A in 2016: elegant, ghostly renderings of the extensive work that underpins something that looks so beautiful once on the body.

Party dresses are essentially Goddard’s stock-in-trade, and when she is not selling a dress, she is at least selling a very vivid idea of a party. Perhaps this is where ‘Dress Portrait’ can move beyond fashion. Goddard’s willingness to pin down an ephemeral moment is matched by Edwards’s desire to capture it in a photograph because the nature of a party means it must eventually stop. The notes that accompany the exhibition state that Edwards does not work with post production or digital manipulation, instead ‘editing’ each photograph as it is shot using colour gels or sheets of plastic. In image, as in reality, fabrics can beguile. The material tulle in particular deceives the eye: by turns concealing or revealing flesh, or doubling in on itself. A photograph of one dress, blurred by movement, suggests the red bloom of a blood stain on a bandage. It is when the photographs separate themselves from the dresses, becoming abstract or alien under these processes, that they seem to have the most to say.

A single dress is also on show, as well as a selection of Goddard’s research materials which include archive photos of veiled children celebrating Corpus Christi in rural Ireland and of traditional Turkish dress for Atatürk Day. Goddard’s brand has become popular as a kind of celebration in and of itself, a riot of pure joyful energy seen infrequently in the fashion industry. Sometimes it seems like fashion, always interested in what comes next, doesn’t know what to do with such joy, but in this collaboration, Goddard seems more able to pin it down, to capture a moment in time. Books from her library are also housed on nearby shelves; they include French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson alongside fashion school staples such as Christian Dior and Yohji Yamamoto. There is a book by one artist in particular that catches my eye: Sculpture, by Turner-prize winner Rachel Whiteread, from the 2005 exhibition of the same name at Gagosian Gallery, London. Whiteread opts for concrete casts of domestic life; meanwhile, Goddard renders the passing of time in tulle and silk, photographed by Edwards through a filter of rain-smeared cellophane. What both Edwards and Goddard seem to share with Whiteread is an interest in making some invisible property of human life become tangible.

Main image: Molly Goddard Dress, 2019. Courtesy: Chelsea Space, Chelsea College of Arts; photograph: Sarah Edwards