Hurvin Anderson

Hurvin Anderson’s exhibition at Ikon, ‘reporting back’, saw the artist returning to his hometown of Birmingham. Tracing 15 years of work, this was the artist’s first survey show in the UK. Often depicting places of leisure – a languid day at the beach, a tennis court, an island of lush vegetation within a city park – Anderson’s landscapes and interiors are subtle explorations of identity, inflected by faded memories.

The exhibition was hung achronologically, loosely in accordance with Anderson’s groupings or series of works. Featuring prominently at the beginning of the show were depictions of Handsworth Park, described as the first landscape to which the artist ‘felt connected’. Migrating from Jamaica in the 1960s, Anderson’s parents settled in this part of Birmingham, which became known for its riots of the mid-1980s – captured in Black Audio Film Collective’s seminal film Handsworth Songs (1986). Initially painting monochromatic, dispossessed scenes, Anderson went on to produce large-scale atmospheric works soaked in colour, such as Lower Lake (2005). The latter bears comparison to Peter Doig’s dreamlike landscapes, and indeed both painters have connections to the UK and the Caribbean. Delicate, calligraphic marks define branches of trees and foliage, amid a striated mass of watery pinks, yellows and oranges; these contrast with vibrant greens and blues to compose a landscape of the imagination – simultaneously familiar and strange.

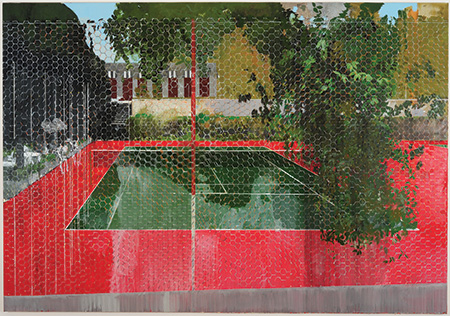

Another strongly represented group was the ‘Welcome Series’ (2002–05), where abstraction and figuration co-exist. Visiting the Caribbean in 2002, Anderson described his sense of dislocation on returning to his family’s place of origin. For example, in Some People (Welcome Series) (2004), the imposing red security grille of a café, signifying both exclusion and protection, is transformed into a starburst-like pattern. Depictions of faceless pin-up models within rectangular posters are scattered throughout the interior, playfully gesturing to the gridded propositions of early modernist painting. Histories of leisure and colonial control are further explored in works such as Country Club: Chicken Wire (2008): tiny hexagons form an imposing geometric fence; through this we view a landscape containing sparkling red tennis courts, sumptuous grass and striped umbrellas. Completely deserted, what could have been a utopian scene becomes silently and eerily oppressive.

One of the exhibition’s most intriguing works, existing outside of a clear series, was Untitled (Livingstone Road) (2000). Its monochromatic palette quietly sung among the surrounding fields of energetic colour. The unnervingly still scene is depicted as if illuminated only by the moon; a road leads nowhere, the depth of field evaporating into the silent night. A modulated grey patchwork of geometric buildings, signposts and uneven tarmac defines the plane, while the vast inky-black sky appears as an endless void.

The impressive ‘Peter’s Series’ (2007–09) – for which Anderson remains best known, with the complete group being exhibited at Tate Britain in 2009 – depicts the sociable space of a barbershop frequented by Anderson and his father during his youth. A sense of fragmented or shifting memory is conveyed through the series, with each rendition either reprising or omitting elements from the last. In Peter’s II (2007), for instance, the space appears as an abstract pattern of turquoise blue, terracotta red and pale grey. Conversely, in Peter’s IV (Pioneer) (2007), these colours are transformed into an interior scene comprising blue walls, a wooden dresser, patterned carpet and curved mirror. These ghost-like objects morph in form and material presence when considered within the context of the group as a whole. Peter’s: Sitters II (2009) focuses specifically on the subject whose hair is being cut. His face, however, is concealed, back turned to the viewer and camouflaged in a checkered shawl of bright pink, orange and yellow; he is as illusive and immaterial as the distant objects. This is a place of in-betweenness that refuses to take form.

The exhibition successfully charted Anderson’s developing style and thematic interests, and was a timely examination of this relatively under-discussed British artist. While the viewer might have benefited from a clearer curatorial framework (labelling was often obfuscated and there was a lack of interpretive material defining the context of each series), the affective experience of these paintings was deliberately unmediated. As a result, one could wander freely and absorb each hazily associative scene, becoming enveloped by colour, pattern and form.