Huw Lemmey and Onyeka Igwe’s Tale of Espionage

At Studio Voltaire, London, a new film narrated by Ben Whishaw asks why the intelligence services proved such an ideal calling for gay men in the early 20th century

At Studio Voltaire, London, a new film narrated by Ben Whishaw asks why the intelligence services proved such an ideal calling for gay men in the early 20th century

To explain why he became a Soviet spy, the anonymous narrator of Ungentle (2022) returns to his first sexual encounter, at the age of 16, with a working-class labourer in a field close to his family’s estate. Looking back on that summer afternoon, he regards their necessarily swift and surreptitious fuck as his first and most vital betrayal. From that moment, he possessed a secret life, and any loyalty he once felt to his country and aristocratic class is overtaken by his identification with the handsome man lying beside him in the grass – a fellow outsider in British society.

Ungentle is inspired by the Cambridge Five, the ring of public-school communists turned double agents who infiltrated the British establishment during World War II. Meticulously researched by writer Huw Lemmey, the narrator’s route into espionage resembles that of Antony Blunt and Guy Burgess: at Cambridge University, he joins a secret debating society called the Apostles and spends long evenings under the spell of the Marxist economist Maurice Dobb. When he is recruited by the Soviets in the 1930s, he becomes an outsider twice over: a communist in the West, and a homosexual when it is a crime to be one.

The question that Lemmey and co-director Onyeka Igwe pose in Ungentle is why espionage proved such an ideal calling for gay men in the early 20th century. The criminalization of homosexuality had compelled gay men to acquire the very skills – vigilance, secrecy and discretion – that intelligence services desired and, because recruitment tended to take place based on personal recommendation among the capital’s secret subcultures, the worlds of espionage and homosexuality were tightly linked. But the film also makes clear that spying was motivated by lust as much as political idealism. The allure of these close-knit, all-male societies of intelligence officials based in and around Whitehall proved powerful to gay men of certain wealth and status who, like the narrator, considered themselves reluctant outsiders.

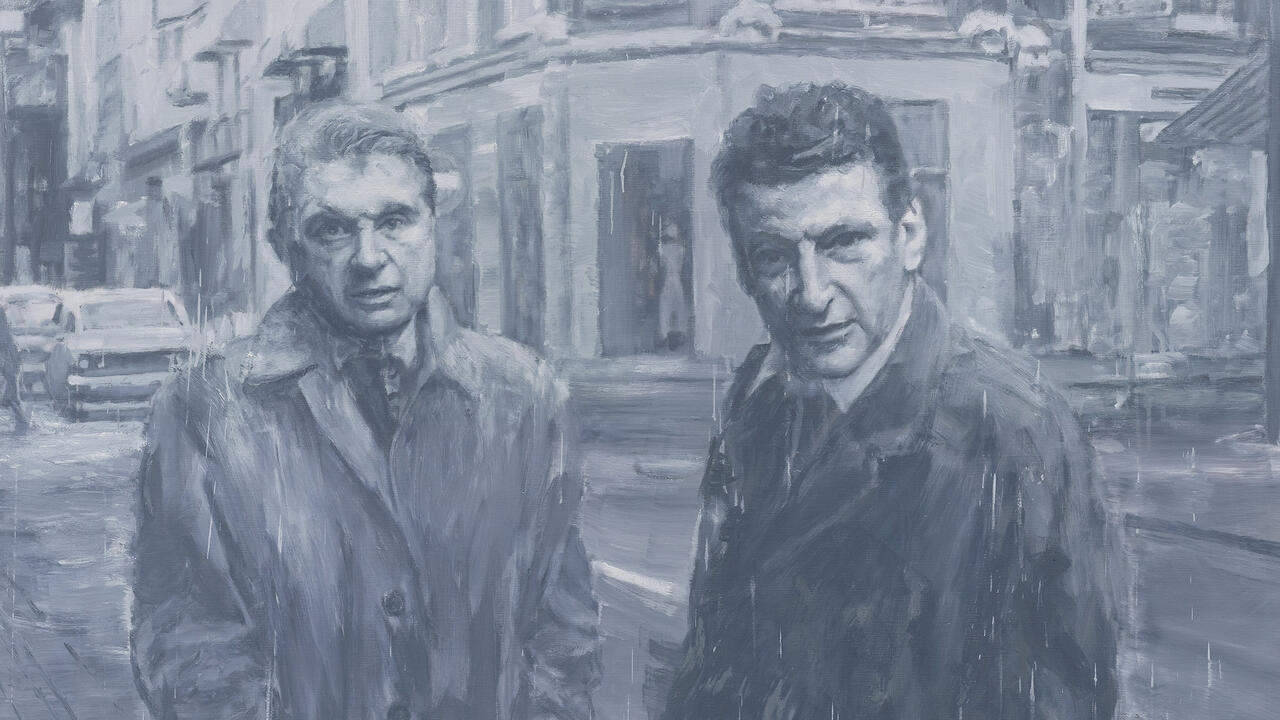

British actor Ben Whishaw voices the spy. His narration is paired with a sequence of images shot on 16mm film, mostly depicting contemporary London: the twinkling lights of Cambridge Circus and Soho, shadowy doorways and passing taxicabs, figures half-glimpsed through dimly lit windows. As the camera loiters in front of 54 Broadway or St. Ermin’s Hotel in Mayfair – both former bases for British intelligence – we are invited to imagine not only the secret rendezvous that once took place behind their elegantly porticoed facades, but also, inevitably, the gay sex.

The narrator is at first unerringly convinced, even exhilarated, by the erotic rewards of his betrayal, but he becomes increasingly anxious about the risks of discovery during the Cold War. When he contemplates the imprisonment of several of his disgraced colleagues, his usual self-regard sounds strained. Fast, echoing footsteps and abrupt camera movements around the courtyard of Dolphin Square, the Pimlico home to many Lords and MPs, suggest his rising paranoia. And yet, despite his contempt for the British people and their thirst for scandal, he confesses he yearns, above all, ‘to be known and recognized for all I was’.

The film alludes to other British men who experienced a formative love for working-class ‘lads’: E.M. Forster, whose writing it quotes, and A.E. Housman, whose poetry, set to rapturous music by George Butterworth, forms part of its soundtrack. Though he cannot be counted among them as 20th century pioneers of queer life, the narrator tells a story that is at once sad and subversive. With careful reserve, Ungentle dramatizes his dawning realization that, despite being one of the chief beneficiaries of the British establishment, protected since birth by his aristocratic class, he has also been its unlikely yet, ultimately, inevitable victim.

Huw Lemmey and Onyeka Igwe’s ‘Ungentle’ is at Studio Voltaire, London, until 08 January 2023

Main image: Huw Lemmey and Onyeka Igwe, Ungentle, 2022, film still. Courtesy: the artists and Studio Voltaire, London; photograph: Morgan K. Spencer