Strolling with Sebald

On his 70th birthday, retracing the writer’s steps along the ‘Sebald walk’

On his 70th birthday, retracing the writer’s steps along the ‘Sebald walk’

The 18 May would have been the 70th birthday of W.G. Sebald. The German writer and academic was born in the Allgäu region of Bavarian Swabia, which straddles Baden-Württemberg to the west and Switzerland and Austria to the south. Sebald, who lived for most of his adult life in the UK, died prematurely in a car crash in 2001, aged 57. Known for his intricate works that coalesced prose fiction, personal memoir and travel writing, Sebald’s stories – while often of minor figures estranged by major events throughout history – frequently played out against the backdrop of a postwar Europe grappling with the memories of its own recent past.

Since reading his Logis in einem Landhaus (A Place in the Country, 1998; 2013) it struck me that Sebald’s geographical and literary roots had almost been prognostic for this particular writer; the German-speaking lands that circumscribe the Alps were also the birthplaces of his literary influences – Johann Peter Hebel, Eduard Mörike and Robert Walser especially, who came from Biel in Switzerland. ‘An interest in locality, notably a rural and island locality, with its suggestions of being “far from home”, is a constant feature of Sebald’s work’, writes Jo Catling in the introduction to her English translation of Logis in einem Landhaus published last year. ‘In these essays’, Catling continues,‘with their loose structuring around an “Alemannic” region comprising south-west Germany and north-west Switzerland and Alsace, we may detect something of a “Ritorno in patria”, a kind of literary homecoming.’

Sebald’s themes of expatriation, uprooting and geographic meditation resonate with the author’s own biography. After studying German language and literature in Freiburg im Breisgau in Baden and Fribourg in French-speaking Switzerland, he moved to England in 1966, first to Manchester before settling permanently in Norwich in 1970 to lecture in Modern German Literature at the University of East Anglia, where he worked for the rest of his life.

This was unbeknown to me when, a few years after his untimely death, I was first introduced to Die Ringe des Saturn (The Rings of Saturn, 1995; 1998) while an art student at what was then the Norwich School of Art & Design. That work is a meditative study of the coastline of Suffolk that puts into motion a chain of personal and historical recollections. Having spent most of my own childhood growing up in the east of England, The Rings of Saturn was something of a revelation – not least because Sebald conjured what was so familial to me into places utterly foreign and fascinating.

In Sebald’s writing, memories pervade landscapes. The clarity of these remembrances, which often become beautifully accentuated by the passage of time, wanders into a nebulous area somewhere beyond biographic fact but not simply literary invention. The story Il ritorno in patria, the concluding text in Schwindel. Gefühle (Vertigo, 1990; 1999) is a homecoming of sorts, though one shrouded in Sebald’s customary melancholia. Here the writer describes returning to his home town of Wertach im Allgäu, where he was born in 1944 and which he often referred to by just the initial ‘W.’

Sebald recalls travelling overnight by train to Innsbruck after a prolonged stay in Verona in the summer of 1987, before his return to England. From Innsbruck he took the only bus to Schattwald, the last stop at the western tip of Austria before the German border, where Tirol meets the Allgäu. Arriving at this outpost after a dismal trip, Sebald set forth on a meandering walk through the bucolic area that lies just north of the Alps to his home town.

Dedicated to his memory by the people of Wertach, the ‘Sebaldweg’ is a twelve-kilometre walk through the Allgovian countryside based on the route Sebald describes at the beginning of Il ritorno in patria. Given its peripheral location, the easiest way to begin the Sebaldweg is to catch a bus from Wertach to Oberjoch (or alternatively, you could ask your landlord for a lift, as is rather charmingly advised in a small printed guide). On an overcast day in April I embarked on the walk, before hiking season began proper. Mist hung around the foot of the surrounding hillocks and slowly moved up their sloping sides. With no clear view of a horizon, I felt encircled by the immediate landscape. As an outsider, retracing the writer’s steps in the landscape of his upbringing served as an elliptical reversal of my feelings reading him traverse the regions of my own childhood.

I joined the Sebaldweg a short distance from its starting point in the meadows somewhere near Krummenbach, where Sebald describes pausing in a small chapel to ruminate on a series of decaying mid-19th century paintings of the Stations of the Cross. Later, as he passes through the tiny village of Unterjoch, he relates Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s travels in 1750 through the Allgäu to Würzburg to paint the ceiling frescos in the Würzburg Residenz of Prince-Bishop Karl Philipp von Greiffenclau. The path diverges before Pfeiffermühle where an old stone tablet engraved with the Tyrolean red eagle stands at the side of the road and continues through a small forested area of Jungholz, an Austrian enclave only accessible from the German side of the border.

‘The last stretch of the journey was as never-ending as I remem-bered it from the old days’, writes Sebald. One finally exits to Wertach from a long bend in the road. As ever in his work, his journey is overcast by ruinous shadows. He re-counts a skirmish that took place at the Enge Plätt in April 1945, when German forces were surrendering. Later he enumerates the terrible events that befell Wertach throughout its history, as told to him as a schoolchild.

‘A good 30 years had gone by since I had last been in W. In the course of that time – by far the longest period of my life – many of the localities I associated with it […] had continually returned in my dreams and daydreams and had become more real to me than they had been then, yet the village itself […] was more remote from me than any other place I could conceive of. In a certain sense it was reassuring, on my first walk around the streets in the pale glow of the lamps, to find that everything was completely changed.’

When Sebald finally arrives at Wertach he checks into the Engelwirt Inn (now the Gasthof zum Engel), above which his family once lived, and which had since been completely rebuilt. He stays here for nearly a month, mostly in seclusion, reminiscing about the eccentric and crest-fallen characters that once populated the village.

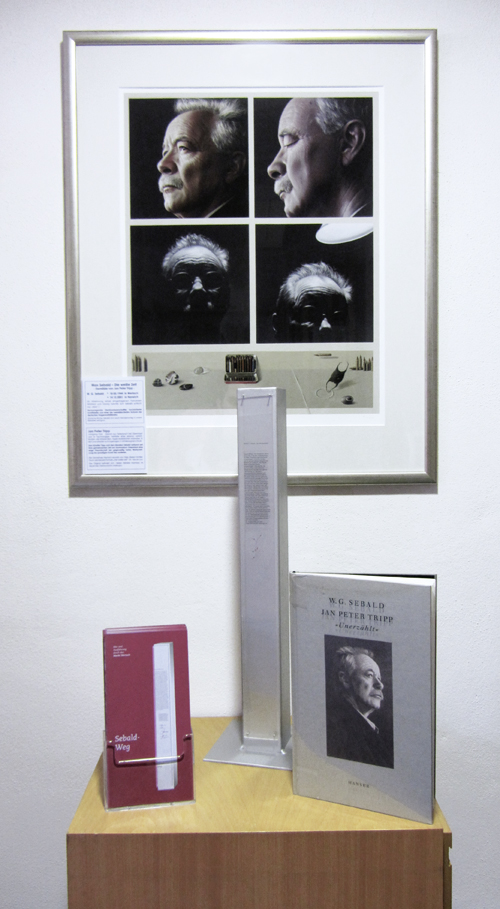

The Sebaldweg comes to an end at a small bridge that crosses a river at the edge of his hometown. In a small library annex of Wertach’s tourist information centre is a bookshelf dedicated to Sebald’s literature. This tiny display houses a selection of various editions of his books published in a number of languages. In its modest way, it shows the breadth of the writer’s appeal, contrary to what Sebald himself said in an interview shortly before his death with regard to the provincialism of 19th-century German prose: ‘[it] was never received outside Germany to any extent worth mentioning’. Happily, now, as Catling says, ‘seismic effects are registered even in the remotest of areas; among which one must count Sebald’s native Allgäu.’