Influences: Betye Saar

The US artist reflects on the art and events that have shaped a career spanning almost seven decades

The US artist reflects on the art and events that have shaped a career spanning almost seven decades

I’ve lived in Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, for about 50 years. I am at a sad place in my life, a crossroads – my brother has just passed away – and I have been thinking about why there is a certain feeling in my artwork that seems grim but really isn’t. The crossroads is about death and rebirth, and how important that is to my practice. I’ve made prints, collages and decorative pieces but the works that I feel are strong and significant are those which revolve around death and rebirth.

One of my best-known pieces is called Black Girl’s Window (1969). It’s a window that I found. The upper panes feature astrological signs, because I’m interested in mysticism; the bottom pane is a portrait of myself with my hands held up and astrological symbols on my palms. At the centre of Black Girl’s Window is a skeleton, and I’ve always wondered: why is death in the centre of a work about my life?

My mother was born in Iowa but raised in Kansas City by her Irish mother and mixed African-American father. My grandmother died when my mother was nine years old, so she was a sad little girl, and that essence of sadness always remained with her. I probably inherited that. Not that I’m not a happy person; I am. But that thread of sadness has worked its way through my work. When I was four years old, and my brother was just an infant, my father died: there was my mother in sadness again. She remarried when I was about 12 years old.

We lived in Pasadena, where we had moved from the Watts neighbourhood of Los Angeles. However, we would spend our summers with my paternal grandmother in Watts, and there I remember passing Simon Rodia as he was building the Watts Towers (1921–55). Right away, I was curious. I was a kid with a lot of imagination – especially fascinated by fairy tales, magic, things like that – and I always wondered what was going on there. The Watts Towers were a strong influence on my work because Rodia used all sorts to make them: iron and steel for the structure, cement, shards. Everything that was thrown away, he recycled. Making art out of nothing – the Watts Towers were where I learned how to be an artist.

As a very young girl, up until the age of around four years old, I was clairvoyant. Then, my father died and I lost that ability. But I still have a sort of psychic intuition and, now that I’m older, when I see something that I know is going to be art then I get it. It’s known as ‘mother-wit’.

My own mother was very sensitive to art: she was a seamstress. I’m a child of the Great Depression and so we made our gifts – a little painting, for instance – and at school, during the summer, we would take art and craft classes. I was always doing something with my hands. My sisters, brothers and I were project-oriented because my mother was always making things – a gift, or an object that we liked.

When I think of the sea of my life, I’m not a strong swimmer, and I never had the stroke for mainstream. But the flotsam and jetsam of tides is what I make my art from; I recycle things that I find. It’s not only materials, images and objects, but feelings and ideas. I put them together and they turn into an art object, collage, assemblage or installation.

Art school was just one of the things black people didn't go to – they didn't study to be artists.

I wanted to study art, but the schools were segregated at the time. The Chouinard Art Institute was available to me, but it was private. You had to apply with a portfolio, and that was just one of the things black people didn’t go into – they didn’t study to be artists.

I studied design at UCLA, from 1947–49, specializing in interior design. Later on, my interior design work – for friends or for my mother – became like making installations. When I first graduated, however, I took a job as a social worker – sociology was my minor – and that was my employment until I married. I worked with old-age pensioners. The experience taught me that it’s really no fun being old; many of the people I assisted were living at poverty level, on meagre allowances, and some of them did not even qualify for social security. I learned a lot about being old and about being poor.

After graduating, I met Curtis Tann, who was to be my introduction to showing art. He was a black designer from Cleveland, and he designed jewellery for a business out here in Los Angeles. He knew other artists who had moved out to the West Coast and that’s how I met the artist Charles White. There weren’t that many galleries in Los Angeles at the time, and there certainly weren’t any for black artists. I didn’t know the Ferus Gallery artists, although I’d heard of Ed Kienholz and saw his piece Back Seat Dodge ’38 (1964), which depicted a couple making love in the back seat of a car, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1966.

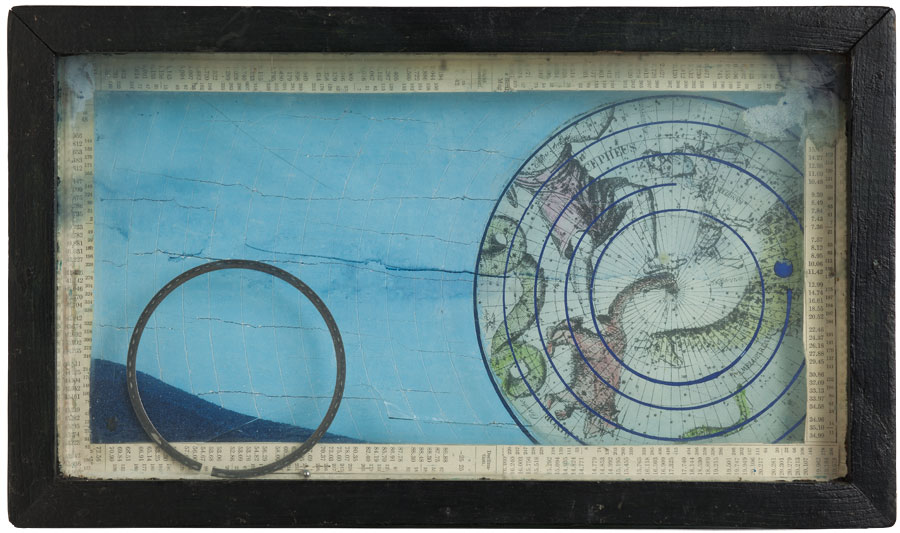

My community was Tony Hill, who made ceramics; the painter William Pajaud, who died last year; Curtis; and, later, Charles. Art exhibitions were held on a weekend, maybe at a social club. There would be a concert or a singer, perhaps, and artists were invited to show their work. At the time, I was a printmaker – intaglio, etchings, serigraphs. Most of the content of my work was mystical: palmistry charts, phrenology, astrological things, signs and symbols. When I started making assemblages, I included my own prints in the pieces.

There weren’t that many houses in Laurel Canyon when we arrived. On the corner of my street is a log cabin where Frank Zappa used to live. The hill section was part of the hippie movement; not that I was really a hippie, because I was a mother with three kids, but we went to love-ins and things like that. Life was always kind of loose anyway because my husband, Richard Saar, was also an artist. He had a company called Saar Ceramics. We made just enough money to pay our rent and keep going.

One Sunday in 1967, my family and I were going to visit my mother for dinner in Pasadena. I said, ‘Let’s go early and we’ll see what’s on at the Pasadena Museum.’ It was a Joseph Cornell exhibition. The galleries were dark; the works were small and carefully spot-lit. They looked like little jewels; they were these magical things. I said to myself: ‘Wow! He just made these out of material he collected.’ I got the catalogue and, from that moment on, I started collecting stuff to make my own assemblages. I spent about three years accumulating material.

My work started to become politicized after the death of Martin Luther King in 1968. But The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, which I made in 1972, was the first piece that was politically explicit. There was a community centre in Berkeley, on the edge of Black Panther territory in Oakland, called the Rainbow Sign. They issued an open invitation to black artists to be in a show about black heroes, so I decided to make a black heroine. For many years, I had collected derogatory images: postcards, a cigar-box label, an ad for beans, Darkie toothpaste. I found a little Aunt Jemima mammy figure, a caricature of a black slave, like those later used to advertise pancakes. She had a broom in one hand and, on the other side, I gave her a rifle. In front of her, I placed a little postcard, of a mammy with a mulatto child, which is another way black women were exploited during slavery. I used the derogatory image to empower the black woman by making her a revolutionary, like she was rebelling against her past enslavement. When my work was included in the exhibition ‘WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution’, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 2007, the activist and academic Angela Davis gave a talk in which she said the black women’s movement started with my work The Liberation of Aunt Jemima. That was a real thrill.

When the activist and academic Angela Davis said the black women's movement started with my work The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, that was a real thrill.

I had a lot of hesitation about using powerful, negative images such as these – thinking about how white people saw black people, and how that influenced the ways in which black people saw each other. What saved it was that I made Aunt Jemima into a revolutionary figure. It came at the right time and if I have an iconic piece, this is it. I was recycling the imagery, in a way, from negative to positive, using the negative power against itself.

Me and my husband had travelled to Europe and North Africa. Later, I also visited Nigeria. I collected metaphysical objects, altars and items related to ancestral history. I remember reading Arnold Rubin’s Artforum article in 1975, ‘Accumulation: Power and Display in African Sculpture’, in which he talked about how certain materials in African art have power and other materials are just for display or to help reinforce that power. That was a strong influence on me. For instance, if I was going to a flea market, a collection of bones and shells would have more power for me than a collection of beads. Once again, it goes back to my intuition – ‘mother-wit’ or whatever you want to call it – about selecting materials that possess power. Rubin described how the borders around a rug are used to protect the inner area. If it is sacred – for instance, a prayer rug – then the inside of the design is the sacred part and the fringe is there to prevent negativity from entering that inner area. I found that very interesting. If you’re making an assemblage, there’s power in a certain part of the piece and then all the rest is decoration, either to throw off the negativity or to attract positive feelings. That’s how I felt about my boxes or collages: the sacred element is located in a particular place in the composition; the rest is just display, used to entice the viewer to look at the work.

In 1975, I had a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. I had often visited The Women’s Building when it was on Broadway in Los Angeles. It was started by the artist Judy Chicago, Arlene Raven, the critic, and the designer Sheila de Bretteville, who happened to live right across the street from me. The Whitney curator Marcia Tucker had come to give a talk and, afterwards, I approached her and said: ‘I’m an older woman, I’m black, and the next time you’re in Los Angeles I would like you to see the work that I do.’ She came by, and that visit led to my show at the Whitney. My exhibition was in the small gallery downstairs – here wasn’t even a catalogue – but it was very popular. People lined up to see it, and that’s when my work became known on the East Coast. The following year, in 1976, Monique Knowlton offered me my first commercial gallery show in New York. I had a certain kind of luck where things just came to me, because I was always shy about approaching a gallery. I think it goes back to my religious beliefs: the best things will come to you; you can try to force things, but it won’t happen or it won’t be as good as you think it will.

Through a National Endowment for the Arts award, I went to Haiti and then, later, through the United States Information Agency, I visited and exhibited in Australia, Taiwan, Thailand and the Philippines. I had lots of solo shows – mostly in schools, university galleries and state colleges – but I didn’t really have a gallery in New York until 1998, when I did a show at Michael Rosenfeld, ‘Workers & Warriors’. Now, I’m with Roberts & Tilton in Los Angeles, because I felt I needed a gallery here in my home town. My first show there was called ‘Red Time’ (2011). It was part of the city-wide ‘Pacific Standard Time’ show, and was a retrospective installation of red objects against red walls. My next exhibition was an installation of works titled ‘The Alpha & Omega (The Beginning & The End)’ (2013), which relates to the crossroads where I find myself now. A version of it appears in ‘Uneasy Dancer’, my retrospective at the Fondazione Prada in Milan. I made a new piece to be included with the installation, When Tears Are Not Enough (2016), which features bottles and a model of a ship. I thought, now why would I give it such a sad name? It went off to be packed the day my brother went into hospital. That’s my ‘mother-wit’ again.

You could say I work with dead objects, with things that people have thrown away: old photographs, and so on. But my work is at the crossroads between death and rebirth. Discarded materials have been recycled, so they’re born anew, because the artist has the power to do that.

As told to Jonathan Griffin, a Los Angeles-based writer and contributing editor of frieze. His book On Fire (2016) is published by Paper Monument.

Lead image: Beyte Saar in front of Simon Rodia's Watt's Towers (1921-55), 1965, photograph. Courtesy: the artist and Roberts & Tilton, Los Angeles; photograph: Richard Saar