Jacolby Satterwhite’s Celestial, Zero-Gravity Dreamscapes

At two solo museum shows, the artist’s animations extend beyond the screen to sculpture, an experimental dance album and merchandise

At two solo museum shows, the artist’s animations extend beyond the screen to sculpture, an experimental dance album and merchandise

‘I feel crazy,’ joked artist Jacolby Satterwhite after opening his first and second solo museum exhibitions, in two different cities, just two weeks apart. To realize his labour-intensive, hyper-baroque vision in ‘Room for Living’, at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, and ‘You’re at Home’ at Pioneer Works in New York, Satterwhite had disappeared for several months from the New York queer scene in which he is a prominent fixture. A flamboyant, rapid-fire intellect, Satterwhite is known for pithy observations and cultural monologues that ricochet from gossip to theory and everything in between – a talent that has often turned his circle of friends, many of them artists and designers, into a kind of late-night focus group for his ideas.

His work has been a mostly solitary endeavour, though, completed in front of a battery of computer screens. Since his series ‘Reifying Desire’ (2011–14) debuted at the 2014 Whitney Biennial, Satterwhite has become known as a builder of intricate, animated worlds. Employing a software called Maya, his films populate celestial, zero-gravity dreamscapes with the intertwined bodies of porn actors, musicians and dancers, like a Hieronymus Bosch painting rendered in Final Fantasy. This fusion is heavily informed by Satterwhite’s personal biography, from his experience of queer visual culture to the prolific creative output of his mother, Patricia. PAT, the band Satterwhite formed in 2016 with musician Nick Weiss, used songs Patricia composed into a tape recorder as the basis for Love Will Find a Way Home (2019), a concept album originally commissioned by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art which, after two years of production, forms the core of the Pioneer Works show.

Satterwhite was born in 1986 in Columbia, South Carolina, in a home he describes as ‘chaotic’. Patricia, who suffered from schizophrenia, was continuously making things: musical albums, drawings, designs for practical (if somewhat outlandish) inventions. His older brothers Jablonski and Henry, who are also gay, taught him how to vogue, and often brought back cassettes of obscure house music from their pilgrimages to New York City’s legendary club and queer mecca, Paradise Garage. In the midst of this, at the age of ten, Satterwhite was diagnosed with cancer. His two-year fight against the disease nearly claimed his young life.

This history informs Love Will Find a Way Home. Together with guest musicians, including experimental pop artist Lafawndah and cellist Patrick Belaga, Satterwhite and Weiss expanded Patricia’s original recordings into haunting, soulful pop songs that create a mood both joyful and melancholic. ‘It takes a low-fi form of expression – folk music recorded onto cassette tapes at home in the 1990s – and elevates it all the way to a 3D animated virtual reality, experimental performance piece and concept album’, explains Satterwhite. ‘We took it from zero to 100, in order to give it re-entry.’ The 14-track, hour-and-fourteen-minute album was released on vinyl at a party at Manhattan’s Ace Hotel, and is available on iTunes and Spotify.

The album cover art for Love Will Find a Way Home shows Satterwhite, in a custom utility vest, partially hidden in an open doorway. The photograph was taken by Wolfgang Tillmans during a late night at the Spectrum, an infamous and now-shuttered underground queer nightclub that Satterwhite refers to as ‘my generation’s Cedar Tavern’, in reference to the favourite haunt of abstract expressionist painters and Beat poets. Footage of Satterwhite dancing at the Spectrum also appears in Moments of Silence (2019), a film in the Pioneer Works show.

Despite his knowledge of the canon, Satterwhite is unafraid to break with the art world’s self-serious conventions. When he first performed Love Will Find a Way Home at SFMOMA, he dressed in a mullet wig on a metal stage, surrounded by smoke and lasers – a presentation more in line with the female pop stars he adores (Grace Jones, Madonna, Janet Jackson) than the tweedy painters he studied in art school. Arriving at Pioneer Works to meet him for a guided tour, I found Satterwhite posing outside, modelling a Burberry jacket for a campaign that designer Riccardo Tisci commissioned for the brand. Satterwhite’s forays into mainstream pop culture also include a collaboration with Solange, whose ‘Sound of Rain’ (2019) music video he animated. Portions of that animation are incorporated into the film Birds of Paradise (2019) on view at Pioneer Works.

The films presented in the exhibition were conceived to match tracks in Love Will Find a Way Home. ‘My mother’s lyrics gave me some visual cues,’ Satterwhite says of animating them, ‘but I also separated myself from them to make what I wanted to make.’ The resulting visual album feels like a cross between Mathew Barney’s ‘Cremaster Cycle’ (1994–2002) and Beyoncé’s Lemonade (2016) – though Satterwhite cites British trip-hop musician Tricky’s 1995 debut album, Maxinquaye, a tribute to the musician’s deceased mother, as his most important influence.

Patricia died in 2016. While her presence is felt throughout the show, Satterwhite hopes audiences will move past the sensationalism of her mental illness and death and explore the many facets of his work. ‘In college, when I learned art history, I was able to reinterpret my mother’s artistic output and see parallels between her work and dada, Fluxus and surrealism,’ he told me. ‘The songs I chose to appropriate are all about resurrection, renewal, and second chances. Her lyrics deal with coming to terms with the fact that she would be schizophrenic for the rest of her life, stuck in the house for the next 20 years. But I don’t let her narrative overtake my own. I’m having my own reconciliation – my Saturn return is ending!’

In addition to a large-scale projection of the titular film and a presentation of his mother’s drawings, Satterwhite’s Pioneer Works show also includes a shop selling affordable merchandise, much of it decorated with those same designs. In suburban Columbia, in the 1990s, the Virgin Megastore was one of the only places where Satterwhite could explore contemporary culture. In addition to copies of the album, the shop sells posters, lighters, and T-shirts commemorating the album release – all of them adorned with his mother’s designs.

In contrast to the New York show, which draws heavily from the mechanisms of popular entertainment, the exhibition in Philadelphia explores the canonical form of large-scale figurative sculpture. Satterwhite, conscious that black and queer artists are often pigeonholed even as institutions embrace them, saw the invitation from the Fabric Workshop and Museum as an opportunity to explore his interest in art history while pushing his work in new directions. ‘Roy Lichtenstein, Carrie Mae Weems, Louise Bourgeois, Nick Cave, Chris Burden! That residency is canon,’ he gushed of the museum’s famous collaborators.

The sculptures in ‘Room for Living’ seem to have danced their way out of Satterwhite’s films and into the gallery. The museum acquired its first 3D printer to fabricate them. The works offer Satterwhite’s audience the opportunity to take in his dense imagery at their own pace – but they also enabled Satterwhite to give life to some of his mother’s inventions. Room for Cleansing (2019), for instance, realizes her design for a hybrid hot tub-lounge chair, to which Satterwhite has added bald, topless women striking provocative poses, in direct reference to Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). A neon sign above the women replicates his mother’s handwritten notation included in the original sketch for the jacuzzi: ‘A water tub seat to soak in.’ A screen mounted on two poles over the tub plays a version of Reifying Desire 5 (2012) split into four quadrants, like surveillance footage, in which the source animation for the tableau appears. The metamorphosis of Patricia’s drawing across media demonstrates Satterwhite’s fluid process of remixing and reinterpretation.

In the exhibition’s largest work, Room for Doubt (2019), Satterwhite has cast himself as each of the apostles – and Christ – in a sculptural tableau of Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601–02). These seven-foot-tall self-portraits – nude save for elegant, floor-length leather do-rags – expand on the homoerotic subtext of the baroque masterwork and its probing of male flesh. In Satterwhite’s version, the wound that Christ invites Thomas to examine is embedded with a small video screen playing Satterwhite’s Robin Battles the Worm Runway (2008), a performance he conceived while a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, a mile and a half east of the museum. The video shows him naked and covered in paint, smearing his body across large, floor-bound images of HIV-infected T cells.

Satterwhite completed his MFA in 2010. In October, not long after his opening at the Fabric Workshop, Satterwhite returned to the university to give a lecture, in which he recalled the late artist Terry Adkins, his professor and mentor at UPenn, sitting him down to watch the music video for Grace Jones’s ‘Corporate Cannibal’ (2008). ‘Like Grace, you need to find economy in your gestures!’ Adkins told him. The advice was transformative: it granted Satterwhite the freedom to ignore the distinction between ‘high culture’, such as fine art, and the world of his pop idols, such as Jones. In Satterwhite’s latest videos, his choreography can be traced as much to ballroom voguing legend Willi Ninja as to ballet choreographer William Forsythe.

At the end of his lecture, Satterwhite reflected on Room for Doubt and its source, The Incredulity of St. Thomas. Caravaggio’s painting, which he copied over and over again as an art student, felt immediately relatable. ‘I almost died a couple of times in my life,’ he said, ‘so I always thought I wasn’t supposed to be here anyway.’ Through repetition, Satterwhite came to see the work as a metaphor for his relationship to art-making: ‘I’m the sceptic, and every drawing or painting I make is the wound. My compulsion to create is to prove to myself that I’m alive.’

Jacolby Satterwhite, ‘You’re at Home’ continues at Pioneer Works, New York, USA, through 24 November. ‘Jacolby Satterwhite: Room for Living’ continues at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, USA, through 19 January 2020.

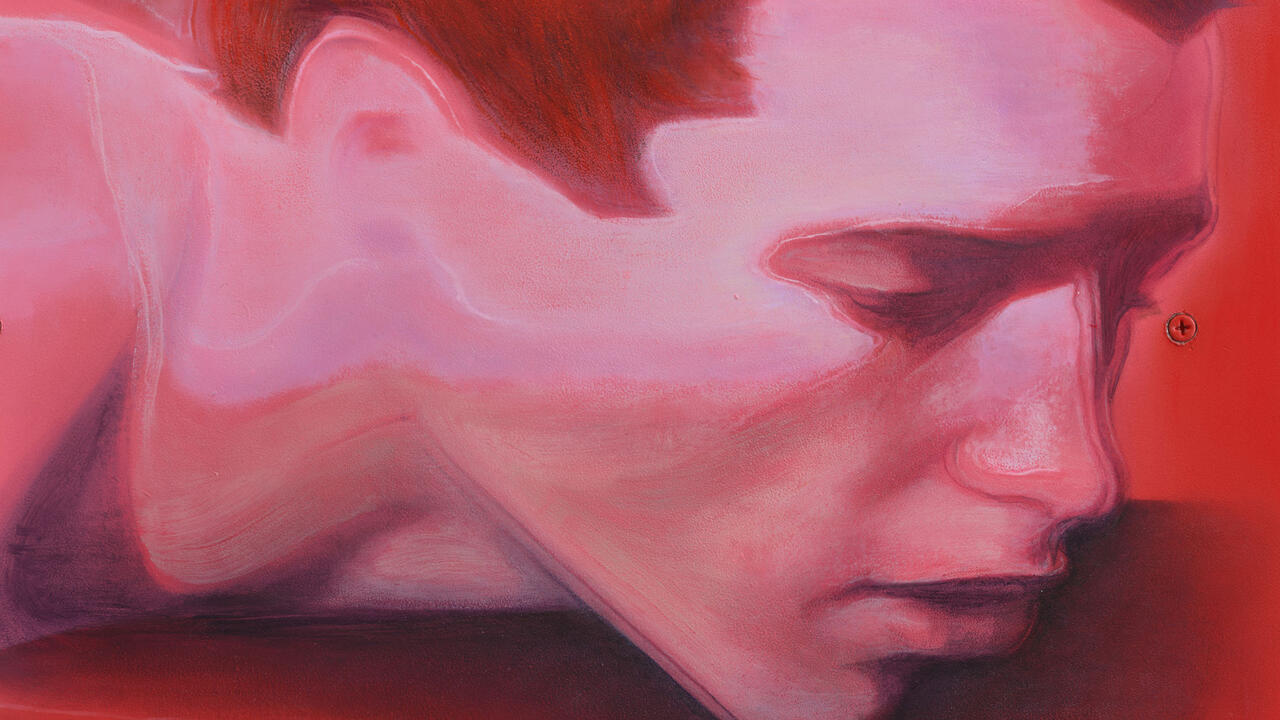

Main Image: Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue (Jade Edition), 2018, video still. Courtesy: © Jacolby Satterwhite and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York