Janiva Ellis’s Paintings of Bodied and Disembodied States

Ellis’s paintings are spring-loaded with overlapping references to film and television, current events, art and cartoons.

Ellis’s paintings are spring-loaded with overlapping references to film and television, current events, art and cartoons.

‘Something strange is creeping across me’ moans the narrator of John Ashbery’s ‘Daffy Duck in Hollywood’ (1975), a poem that ventriloquizes the lisping, titular Looney Tunes character as he fathoms that he is not a real duck, but a cartoon. In a lengthy monologue, Daffy flips out, quacks a litany of products (‘Rumford’s Baking Powder, a celluloid earring’), bemoans the ‘mutterings, splatterings, / The bizarrely but effectively equipped infantries of happy-go-nutty / Vegetal jacqueries …’ and so on. The poem – a landmark text of American postmodern poetry – collates different voices and tonal registers, from the jocular to the melancholic, all voiced by Daffy. The names of world events, book characters and the capitalist flotsam and jetsam of mid-century Americana wells up, quite suddenly, within him as he is walloped by discourse and history. Caught in the poem’s mental storm, the duck folds a personal crisis into a historic one: capitalist America is never what it seems to be and undergirding our daily experience is a worrying world of too much stuff. ‘Not what we see but how we see it matters,’ he declares. ‘All life is but a figment.’ And life, Daffy concludes, ‘our / Life anyway, is between.’

In 2016, Janiva Ellis – a painter of densely layered portraits that often incorporate cartoon forms and sly references to US pop culture – was living in Los Angeles after working a six-week shift as a bartender on an Alaskan cruise. She had recently spent a year in Hawaii, where she was raised, and, prior to that, she had lived in New York, which is where I met her. Strangeness had crept into everything that year, as the election of President Donald Trump curdled the national mood. On social media, anxious memes about the state of the world proliferated. Ellis noticed that Daffy Duck had become a recurring image on Instagram, a sort of cartoon emblem of our collective crack-up. ‘Me’, users captioned his face, which in pictures was often a smouldering ruin thanks to the well-aimed gun of his perennial pursuer, Elmer Fudd. After a hiatus from art-making, Ellis had the idea to include Daffy Duck in a metre-tall portrait of her friend and fellow artist, Jasmine Nyende: Hunt Prey Eat (2017). She had already been experimenting with cartoons in a series of new, densely colourful paintings; Daffy, in his ready-made form, allowed her to immediately render a face – and build toward a narrative.

In Hunt Prey Eat, Nyende’s face – her features and hair blurred in a wash of black paint – swallows the bulk of the canvas. She appears to be in a pool, floating on a crumpled, blow-up horse, its form partially deflated. Behind her, in the middle distance, Daffy turns his head to the left while his eyes leap absurdly to the right. Another toon lurks at the surface of the water. A sign behind it reads: ‘Live Laugh Hunt!’ Blood – from whose body? – sprays the air. The portrait is unsettlingly pretty, with a tone that reminds me of Ashbery’s own portrait of Daffy-in-disarray (‘What’s keeping us here? Why not leave at once?’). It also recalls Dajerria Becton, a 15-year-old black girl who was wrestled to the ground by a white police officer named Eric Casebolt at a pool party in McKinney, Texas, in 2015. (The painting, Ellis told me, wasn’t intended as a portrait of Becton but, after she completed it, the resonances with the incident in Texas were clear.) Mobile-phone footage circulated widely on social media and joined a stream of images of black and brown bodies being aggressively targeted by the police during seemingly mundane events: riding in cars, leaving grocery stores, spending a day at the pool. In 2016, this was not a new story, but a more widely broadcast one – and one echoed not only in the painting’s present figures but in its absent ones, too. Officer Casebolt and Elmer Fudd are nowhere to be found.

Ellis’s paintings are spring-loaded with overlapping references to film and television, current events, art and cartoons. In Dashland Updrown (2019), for example, a hand dips an Ellsworth Kelly painting into a cup containing, in miniature, the American actors Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek as they picnic in Terrence Malick’s 1973 film Badlands. A cartoon – stretched so thin as to be almost anatomically unrecognizable – chases its tail around the cup. The painting’s composition refers to the opening of Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991), when a hand reaches down to grab a book and the camera trails, for a few seconds, on a glass of water containing baby’s breath. (The colours of the Kelly painting and the flowers are inverted from their originals.) Other works are more ambiguous in what, and how, they draw on an existing world of images. Bramble’s Briar Patch (2018) depicts a curtseying young girl dressed as Snow White from the 1937 Disney cartoon; her head is slightly bowed, revealing a shadowed face behind her mask. Her real eyes are barely visible, but her furrowed brow seems to suggest worry.

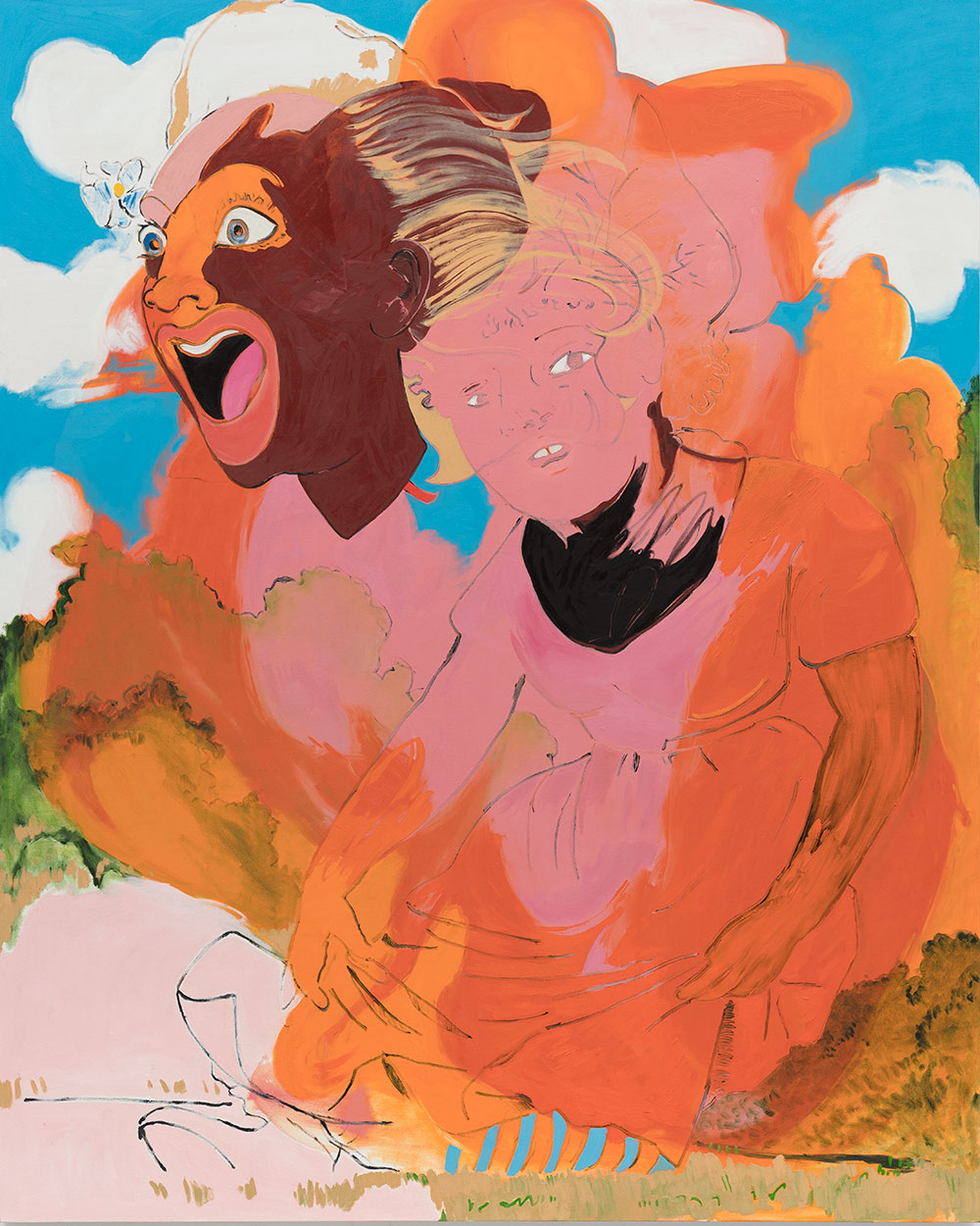

Ellis’s work bursts with a bright lust for life as her figures, whether fully fleshed-out or appearing only in outline form, move between embodied and disembodied states – caught, it would seem, mid-transformation. In Thrill Issues (2017) – which was first exhibited at the 2018 New Museum Triennial, ‘Songs for Sabotage’ – the subtle outline of a young girl is interrupted by the laughing, wide-eyed head of another woman. They are both enclosed in a pink and orange, fiery burst, as if they have risen from the surrounding country landscape, Phoenix-like, enthralled by their sudden explosion into painterly existence. To borrow a line from another Ashbery poem: ‘Yes, they are alive and can have those colours.’ But the stakes of these metamorphoses, and of her paintings’ referential drift, intensify when considered in terms of the political and social realities that buffet her human and cartoon subjects. Within many of Ellis’s paintings, the collective and individual histories of trauma that attend to the anti-blackness at the heart of American life coil alongside the levity, however ambiguously rendered, that allows for trauma to be survived.

In his introduction to Black and Blur (2017), poet and theorist Fred Moten writes: ‘Black art neither sutures nor is sutured to trauma. There’s no remembering, no healing. There is, rather, a perpetual cutting, a constancy of expansive and enfolding rupture and wound, a rewind that tends to exhaust the metaphysics upon which the idea of redress is grounded.’ Building on his earlier book, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (2003), Moten is referring to a moment in the memoir of 19th-century activist and writer Frederick Douglass, where he witnesses an attack on his Aunt Hester by a white man. Douglass describes the incident as an ‘entrance to hell’, the details of which he cannot fully commit to paper, though her scream continued to echo in his mind for the rest of his life. That scream, Moten writes, is ‘not simply unrepresentable but instantiates, rather, an alternative to representation’. It disrupts both description and meaning itself.

In Hunt Prey Eat, Nyende’s face forms a negative space, even a hole, at the centre of the painting where her haunting, expressive features and the meaning those features might convey partially lapse beyond representation. What does she say or what might she cry out? She doesn’t so much recede into shadow, or the blur of black paint, as she disallows interpretation of her expression; I cannot ‘read’ the ‘content’ of a face that might convey to me what, exactly, she is feeling. These disruptions, or even denials, of art’s ability to fully render lived experience become, in Ellis’s work, an underlying aesthetic principle: it is not what we see but how we see it that matters, and so each subject, each body and face and limb and set of eyes simultaneously concedes to and subverts its representation in paint. In doing so, they remind us, in part, of the vexed dimensionality of the world outside the painting, where real-bodies-in-real-space are constantly subjected to and shaped by the threat of direct and indirect violence.

But the starkness of trauma, in Ellis’s work, is often linked to humour. Together, they form a double-helix-like tonal structure, in which both helices are connected through the artist’s references to pop culture and her comic formalism. In a 2019 interview with X-tra magazine, Ellis describes one painting, Co-Panicing (2017) – in which a decapitated human head flies above a cartoon one – as an image that ‘implies both stress and jest’. Her paintings, she says, form ‘a language that functions like a gloved hand, muting its individuality yet exaggerating its gesture’. Behind the false Snow White in Bramble’s Briar Patch lurks a lanky puma, its ears fading into the blue sky. Its toothy smile recedes into the bushes, and it seems to offer its face – no more real than Snow White’s mask – as a respite or break from the more complex human subject at the painting’s centre.

Other pieces use cartoons more explicitly – and exclusively – to unwind ideas of figuration and narrative and, in doing so, provide a certain slyness to her work’s persistent interest in the disorderly nature of bodies. In Duck Duck Deuce 2 (2017), Daffy’s head bursts through his red beak; his eyelids are fat and heart-shaped, like lips – a reimagining of the duck that pushes his already-wild features to more absurd abstraction, forming a sort of crazed, kissy face. These paintings, in their sudden turn towards overt goofiness, disclose a different world from the one from which they draw their more violent elements, a world always seemingly in the midst of becoming. It is a colourful elsewhere, another place, a not-here and a nowhere-is-Fudd-to-be-seen. In this world, which is never fully complete, Ellis’s metaphorical registers dive into still deeper states of ambiguity as references splice and trouble one another to form new meanings. They come together and then they come undone.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 203 with the headline ‘What’s Keeping Us Here?’

Main Image: Janiva Ellis, Co-Panicing, 2017, oil on canvas, 76 × 57 cm. Courtesy: the artist and 47 Canal, New York; photograph: Joerg Lohse