Jean Dubuffet

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

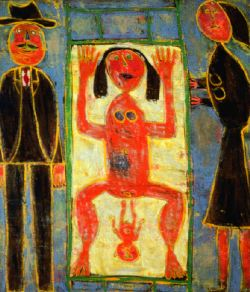

I wasn't surprised to see Jean Dubuffet's name included in Peter Davies' pithy painting of a list, Hot One Hundred (1996). Even though he only comes 52nd, after the likes of Bruce Nauman and Andy Warhol, Dubuffet can still be described, like them, as an artist's artist: one whose work is too full of good ideas not to be influential. At the time of his death in 1985 he was well represented in international museums and had been commissioned to do many public sculptures, but his obsessive multi-faceted oeuvre always makes apparent the full process of creation, complete with trial and error. His thick, mud-colour asphalt paintings - what Davies calls his 'grungier ones' - which, in the mid-1940s displayed a sad tendency to melt in the overheated New York flats where they found homes, are just one example of how much Dubuffet's work embodies (like Marcel Duchamp's snow shovel) the prospect of their self-destruction and inevitable failure. The question of failure became central for Dubuffet from the moment he began, in the late 1940s, to hail Art Brut as the only true form of artistic creation. Following this principle, his endeavour could not be any more than an adulterated contraption, an everlasting approximation to the real thing.

Dubuffet relentlessly pursued a practice in which he explored one brilliant idea after another, but without pursuing them to their most extreme outcome. That the artist stood between generations (he was born in 1901 but only began his career in 1942), gives the impression that his work resonated, yet was alien to that of his contemporaries. His paintings make you wonder, for instance, why anyone would bother to graffiti a wall when you could take a picture of one, as Brassaï did; or paint dust ('Texturologies', 1957-9) when you can 'raise it' (Man Ray and Duchamp's Élevage de poussière, 1920), or even pack it neatly into a box (Robert Rauschenberg's Dirt Painting, 1953). Why depict a shopping extravaganza ('Paris Circus', 1961-2) when you can simply create your own shop (Claes Oldenburg's The Store, 1961)? There are some obvious replies to such questions, but raising them simply points out Dubuffet's oddness in time and place, an oddness that influenced younger artists concerned with the relation of high art, vulgarity and vernacular expression, including Oldenburg, Julian Schnabel, Keith Haring and Mike Kelley.

Given these parameters, the challenge of a Dubuffet retrospective today would be to point out these contradictions as they emerge from the works, and to propose intersecting threads that could be explored in his massive output. Working in series, Dubuffet's creative output followed less a linear pattern than a hectic web of interrelated strands, a configuration that is strangely played down by this show. However, instead of revealing this lack of linearity, the rooms unrolled what felt like a smooth narrative progression.

The 400 or so paintings, sculptures and drawings included in this show, which was curated by Daniel Abadie and Sophie Duplaix, were displayed in a large immaculate space which seemed to cleanse the work of its materials (the captions only rarely gave a full account of the materials used in the pictures). The series 'Matériologies' (1959-60) and 'Texturologies', for example, which aimed to evoke undetermined stretches of ground, were lent a strangely immaterial feel by the shiny white floor in which they were reflected. Elsewhere, the curators' desire to confirm the harmonious continuum of Dubuffet's oeuvre was apparently the reason for juxtaposing paintings and drawings. The unhappy effect of this, beside the difference of scale between works, was the flattening of the paintings by the subdued lighting necessary for the drawings.

These display problems set aside, the selection of work revealed some strange absences, such as the 1952 series 'Tables', depicting textured tabletops, which epitomizes Dubuffet's conceptual drive for an art that 'addresses the mind, not the eyes'. Other series were badly presented: the penultimate and exuberant series 'Mires' (1982-3) clashed with the more austere 'Non-Lieux' paintings (1985) he completed shortly before his death.

It was, in the end, apparent that the curators wanted to keep Dubuffet locked up in an ivory tower furnished only with Art Brut. In avoiding an exploration of the complex contradictions of his art and its intense dialogue with the art of his time, they missed out on the more stimulating ideas his work can still provide.